Wisconsin 101 is proud to collaborate with Wisconsin Public Radio’s Wisconsin Life, an award-winning radio show that celebrates what makes Wisconsin unique. Every few weeks, Wisconsin Life will feature a new object from the Wisconsin 101 collection. Enjoy those radio segments below, ordered by most recent air date.

Wisconsin Life/Wisconsin 101 Broadcasts:

Essay by Jared Lee Schmidt

Produced for Wisconsin Life by Maureen McCollum and Heewone Lim

Many people preserve their genealogy through family trees, mapping the branches and roots out on paper. Heewone Lim brings us the story of a unique genealogical work of art: a Norwegian genealogical plaque.

Listen below to the segment from Wisconsin Public Radio’s Wisconsin Life.

Maureen McCollum:

Many people preserve their genealogy through family trees, mapping the branches and roots out on paper. Heewone Lim brings us the story of a unique geological work of art, a Norwegian plaque. It’s part of the Wisconsin 101 collection, which tells the history of the state through objects.

Heewone Lim:

In 1879, Hans Gunther Magelssen of Norway commissioned a jeweler in Oslo to create a gift for his granddaughter-in-law, Sarah Magelssen. The gift was a round wooden plaque inset with a five Øre coin, the equivalent of a nickel. Surrounding the coin are 18 circles of names and important dates chronicling the Magelssen family genealogy. The dates note births, marriages and when people emigrated to the United States. Dana Kelly is the executive director at the Norwegian American Genealogical Center and Naeseth Library. She says this plate is a one-of-a-kind genealogical artifact.

Dana Kelly:

The things that they brought with them were pretty utilitarian, but to have just an artistic object like this was pretty unusual.

Heewone Lim:

Kelly says the center sees other genealogical objects such as trunks with names painted inside the lid, or family Bibles, where a family has several generations of baptisms and marriages recorded.

Dana Kelly:

But obviously a Bible is not created just for genealogy. It’s meant to be a book. So this is unique in that respect, that it was created specifically for genealogy to tell the family’s history.

Heewone Lim:

Certain names on the plate are underlined over and over, which was a practice used in church records back in Norway, the Magelssens had ministers in the family tree, so they likely carried on this practice for generations.

Dana Kelly:

You know, I baptized so-and-so’s daughter, you know, Kari, he would underline Kari’s name because that was the important part. That was the child being baptized. It does kind of look like they’re doing that here, underlining the person’s name to accentuate who’s the important person on this line. So they’re keeping with that custom.

Heewone Lim:

The plate begins with a different Hans Gunther Magelssen, who was born in Hamburg, Germany in 1734 and emigrated to Norway in 1756. Magelssen’s German roots explain why the family has the same last name throughout the plate. Kelly says the practice of using a permanent family name was uncommon in Norway at the time.

Dana Kelly:

Their social custom was not to give children the same last name as their father. If their father’s name was Lars, the children would be Larsdatter or Larsson. So seeing that they refer to themselves as the family Magelssen would indicate to me that they have a cultural outlook that isn’t typically Norwegian. Perhaps they had had more experience with other cultures in Europe that have that permanent family last name.

Heewone Lim:

However, the family still kept some Scandinavian naming traditions. The plate features a few different names multiple times, Hans Gunther Magelssen, Sarah Magelssen and Kristian Magellsen.

Dana Kelly:

Names got used over and over and over again in Norwegian families that it was very common to name a child after their grandparent, and it wasn’t unusual to have more than one child in a family that had the same name.

Heewone Lim:

The value of this plaque both a carefully crafted artisanal object and a sentimental record keeper speaks of the dedication the Magelssens had to keeping Norwegian culture and their family history alive in the Upper Midwest, sending a family heirloom to America, a far away country with no practical purpose, reflects the journey of the Magelssen family.

Dana Kelly:

Something like this would have been something that they could display freely without having to worry about discrimination and what it might mean to cling to the old country, so to speak.

Heewone Lim:

By 1870, almost 60,000 Norwegians had settled in Wisconsin, and that included members of the magelson family the United States became known as westerheim, or the Western home

Maureen McCollum:

Heewone Lim brought us that story on the Norwegian geological plaque, which is part of the Wisconsin Historical Society’s collection. It’s also a part of the Wisconsin 101 Project, which tells the history of the state through objects. Wisconsin life is a co-production of Wisconsin Public Radio and PBS Wisconsin in partnership with Wisconsin Humanities. Additional support comes from Lowell and Mary Peterson of Appleton. I’m Maureen McCollum.

Essay by Kaylee Bittner

Produced for Wisconsin Life by Maureen McCollum and Heewone Lim

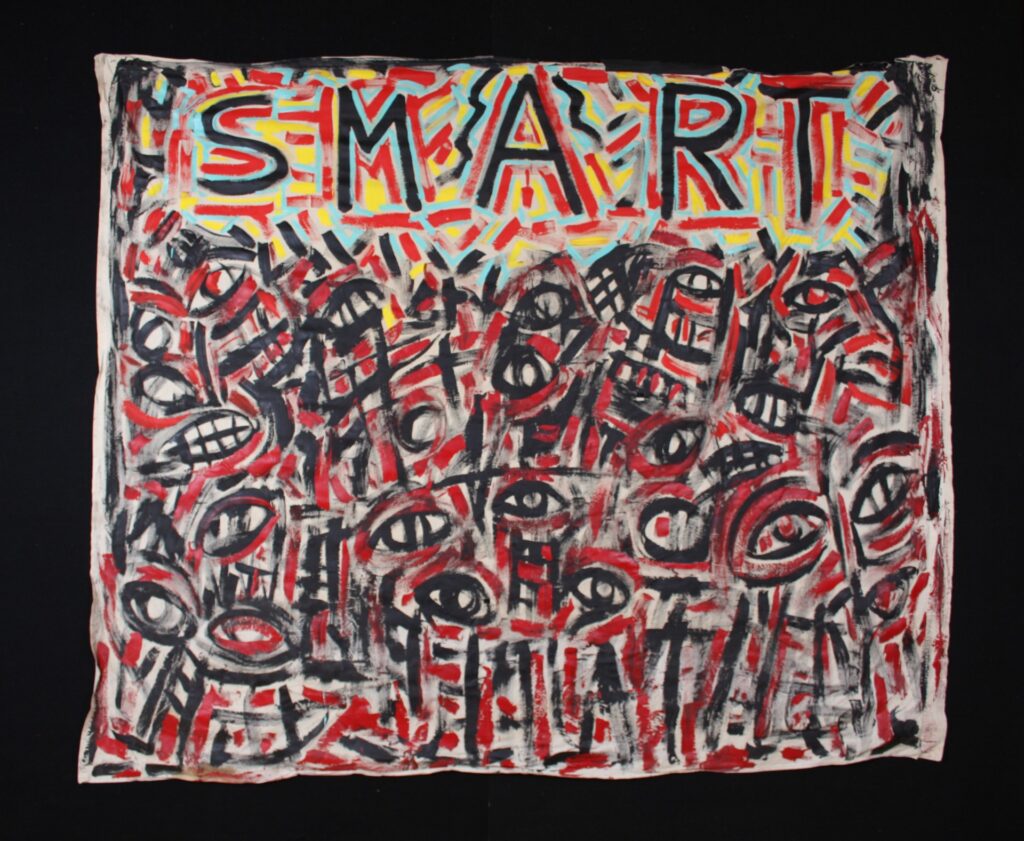

In the Wisconsin Historical Society collection, there’s a dark, surreal black and red banner. It’s painted with a chaotic collection of eyes and mouths seemingly calling out to the bold word above them: SMART. This banner served as a backdrop in the legendary Smart Studios in Madison beginning in the early 1980s. It’s a space that recorded iconic Wisconsin bands, like Killdozer and Die Kreuzen, and eventually rock n’ roll legends like Nirvana and Smashing Pumpkins.

Listen below to the segment from Wisconsin Public Radio’s Wisconsin Life.

Maureen McCollum:

In the Wisconsin Historical Society collection, there’s a dark, surreal black and red banner. It’s painted with a chaotic collection of eyes and mouths seemingly calling out to the bold word above them: SMART. This banner served as a backdrop in the legendary Smart Studios in Madison beginning in the early 1980s. It’s a space that recorded iconic Wisconsin bands, like Killdozer and Die Kreuzen, and eventually rock n’ roll legends like Nirvana and Smashing Pumpkins.

Heewone Lim brings us the story of this unique piece of art that once hung in Smart Studios. The “SMART” banner is part of the Wisconsin 101 project, which tells the history of the state through objects.

Heewone Lim:

The story of the “SMART” banner begins with Butch Vig and Steve Marker, two friends and musicians from UW–Madison. The duo opened Smart Studios in 1983 on the east side of Madison. Their recordings hold a legendary space in punk, rock and grunge music history.

Smart Studios first location in the Grisholt building was down the hall from visual artist Dennis Nechvatal’s studio. The first year they were open, Nechvatal created the “SMART” banner for his new neighbors.

Dennis Nechvatal:

We were in communication a lot … just down the halls and drinking beer and misbehaving and stuff like that. So we got to be quite friendly and still are. It just sort of progressively became what it was. I didn’t intentionally put it out there to be a banner or signature statement for their situation, but it all just came into play.

Heewone Lim:

When Vig and Marker moved Smart Studios to its second location on East Washington, the banner came with.

Dennis Nechvatal:

That’s when Smart started to get very serious. That’s when the bigger bands and everybody starts showing up.

Heewone Lim:

Bands like Smashing Pumpkins, L7, and … Nirvana. Vig and Marker would eventually record their own electronic rock band, Garbage, at Smart Studios.

The “SMART” banner served as a backdrop to these important moments in music history. And, it stands out from Nechvatal’s other artworks, which heavily feature nature, but he still used familiar elements, such as surrealism and facial features.

Dennis Nechvatal:

It’s sort of blending the modern and the primitive together. Modern sort of seems to be out there, but there’s always tomorrow, so it changes. The eyes and the primitive, it’s sort of a motif in all my work.

Heewone Lim:

The banner represents a time in Nechvatal’s life as a young up-and-coming artist. In fact, the materials used to make the banner are unexpected: acrylic paint and secondhand sheets.

Dennis Nechvatal:

I always had an abundance of discarded sheets and they were always cleaned up and so I just stapled that one sheet to the wall and gave it hell.

Heewone Lim:

But what really makes the “SMART” banner unique is the pure, unbridled creativity that went into it.

Dennis Nechvatal:

Give it a shot, you know? Try it. I still do that, but not with the comfort that I used to. Because now, it’s like, I gotta sell a painting.

Heewone Lim:

Nechvatal says that Smart Studios and his own art career took off around the same time.

Dennis Nechvatal:

And so Smart Studios was just part of the growth, ya know? We were all sort of starting together. ‘Cause I was starting to sell paintings in Chicago and other places and bigger cities like that. The whole movement sort of started and just sort of kept going.

Heewone Lim:

But he hasn’t forgotten the humble beginnings of the now historic studios.

Dennis Nechvatal:

It came out of the basement, too, you know what I mean? It can come out of anywhere. It doesn’t have to be out of the big city. A situation like that. Once it germinates, it can be nurtured, and all of a sudden you’ve got something brand new.

Maureen McCollum:

Heewone Lim brought us that story on the Smart Studios Banner, which is part of the Wisconsin Historical Society’s collection. It’s also a part of the Wisconsin 101 project, which tells the history of the state through objects. Wisconsin Life is a co-production of Wisconsin Public Radio and PBS Wisconsin in partnership with the Wisconsin Humanities Council. Additional support comes from Lowell and Mary Peterson of Appleton. I’m Maureen McCollum.

Produced for Wisconsin Life by Maureen McCollum and Heewone Lim

In the early 1940s, many women stepped up to the plate to become professional baseball players after most men were drafted to serve in the military in World War II. They became players in the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League.

Heewone Lim brings us the story of the players on the Racine Belles and specifically their uniform — which was a dress. It was made famous in the 1992 film, “A League of Their Own.”

Listen below to the segment from Wisconsin Public Radio’s Wisconsin Life.

Maureen McCollum: In the early 1940s, many women stepped up to the plate to become professional baseball players after most men were drafted to serve in World War II. Heewone Lim brings us the story of the players on the Racine Belles and specifically their uniform — which was a dress. It was made famous in the 1992 film, “A League of Their Own.” One of the movie’s costumes is a part of the Wisconsin 101 collection, which tells the history of the state through objects.

Heewone Lim: In 1943, Philip Wrigley, a gum manufacturer and owner of the Chicago Cubs, came up with an idea. Professional baseball players had to turn their attention to WWII, but that didn’t mean baseball had to go away. So, he formed the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League. Wrigley recruited players from across the country, but the first four teams were based in the Midwest. Two were based in Wisconsin: the Kenosha Comets and the Racine Belles.

The Belles were briefly featured in the movie “A League of Their Own.” Although the film came out over three decades ago, the iconic costumes have stood the test of time.

Soundclip from the film: “Ya’ll have to get fitted for your uniforms, and this is what they’re gonna look like. Pretty darn nifty if you ask me. [whistles] How ‘bout that, Billy.”

“We can’t slide in that!”

“Hey that’s a dress!”

“It’s half a dress!”

“Excuse me, that’s not a baseball uniform!”

“Yeah! What do you think we are? Ball players or ballerinas?” [laughs]

Heewone Lim: Costume designer Cynthia Flynt said she consulted former players and clothing catalogs from that time period.

Cynthia Flynt: I received a whole uniform, socks, belt, those little undershorts. Really, I just copied it.

Heewone Lim: The uniforms worn by the female ballplayers, consisted of a belted, short-sleeved tunic dress with a flared skirt. Flynt said the lack of protection from the skirts led to injuries.

Cynthia Flynt: I mean, I guess the thing that was always so striking was about that they had to wear these skirts and the injuries that they got from sliding in, ya know, the bruises and the scrapes. I mean, their thighs were a mess.

Heewone Lim: Former Racine Belles player Sophie Kurys talked about this in an interview with Grand Valley State University. She said the red abrasions from sliding into dirt base-running were called “strawberries.”

Sophie Kurys: I had strawberry upon strawberry. Even today, sometimes when I get up in the morning, I say “uh oh, this bothers me a little bit, but not bad. When it’s sore, it leaks, but our chaperone was pretty sharp. She made a donut affair and put it across the strawberry so that it wouldn’t leak on my clothes because if it did, man, it would stick to you and you would have to pull that off and you’d be in agony.

Heewone Lim: Rules stated that skirts were to be worn no more than 6 inches above the knee, but the regulation was often ignored so players could run and field. The players also attended a charm school to ensure that they displayed “ladylike” behavior.

Kurys said players always had a skirt or a dress on hand in case they needed to go in public.

Sophie Kurys: And, ya know, when we had a pit stop, the girls — if we had shorts on — we had to put dresses or skirts on because we never could be seen in public in shorts or slacks. Never.

Heewone Lim: When taking the characters’ backgrounds into consideration for the costume designs, Flynt said the players’ reactions to playing baseball in skirts makes sense.

Cynthia Flynt: I mean, those women were farmers and wore pants and overalls. And I think there was a genuine like, ‘Really? We have to wear dresses? This is insane.”

Heewone Lim: The Racine Belles played for eight seasons in Wisconsin from 1943 until 1950, when they moved to Michigan. The team relocated to Battle Creek and then to Muskegon, playing three more seasons, but the Belles folded in 1953. The rest of the league went out of business in 1954. The All-American Girls Professional Baseball League was quietly forgotten until the release of “A League of Their Own” 40 years later, which grossed more than $132 million at the box office.

Maureen McCollum: Heewone Lim brought us that story on the Racine Belles movie costume which is part of the Wisconsin Historical Society’s collection. It’s also part of the Wisconsin 101 project which tells the history of the state through objects. Wisconsin Life is a co-production of Wisconsin Public Radio and PBS-Wisconsin, in partnership with Wisconsin Humanities. Additional support comes from Lowell and Mary Peterson of Appleton. I’m Maureen McCollum.

Essay by David Driscoll, Wisconsin State Historical Society

Produced for Wisconsin Life by Molly Hunken

In the early 20th century, millions of Jewish people fled Russia due to persecution and poor quality of life. Some of them ended up in Wisconsin. In Sheboygan, a former synagogue with an historic stained glass window acts as a testament to the area’s once thriving Jewish community.

Listen below to the segment from Wisconsin Public Radio’s Wisconsin Life.

Maureen McCollum: In the early 20th century, millions of Jewish people fled Russia due to persecution and poor quality of life. Some of them ended up in Wisconsin. In Sheboygan, a former synagogue with an historic stained glass window acts as a testament to the area’s once thriving Jewish community. Molly Hunken brings us their story.

Molly Hunken: Most Jewish people who immigrated from Eastern Europe to the United States came to cities, but some did settle in smaller towns. One such community was Sheboygan, Wisconsin.

With a population nearing just 23,000 by 1900, the town of Sheboygan was small, not somewhere you might imagine large groups of new U.S. immigrants flocking to. However, according to Susie Alpert Drazen, was where employers were hiring. Her first family member arrived there in 1904.

Susie Alpert Drazen: They said, “Well,” and pointing to a map of the United States, “You can find work here, here, and here. And they’re hiring here, here, and here.” So they fronted him train ticket money, and away he went to Sheboygan, Wisconsin.”

Molly Hunken: The first synagogue in Sheboygan opened its doors in 1903. And by the time Drazen was growing up there, Sheboygan was home to three synagogues.

Susie Alpert Drazen: The synagogue that my family belonged to, it was called The Brick Shul — shul being a Yiddish word for synagogue. That was because it was made of bricks. There was also a White Shul, because it was white. And then there was the Holman Shul, which the Holman family founded.

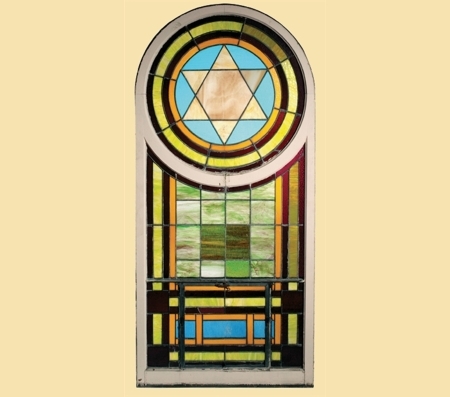

Molly Hunken: The White Shul had originally formed in the 1890s as an Orthodox congregation called Adas Israel, meaning “Community of Israel.” The architecture of The White Shul included a large onion dome at the top of the building as well as a stunning stained glass window that featured a Star of David.

David Driscoll: The window is about six-and-a-half feet high and three feet wide.

Molly Hunken: That’s David Driscoll, a curator at the Wisconsin Historical Society. He showed me the window, which is now hanging up in their storage facility.

David Driscoll: And in the middle there’s a leaded glass Star of David, that’s kind of a mottled white and brown color.

Molly Hunken: The Wisconsin Historical Society has been able to preserve this key remnant of Adas Israel. And according to Susie Drazen, the window’s material has an important purpose in Jewish culture and religion.

Susie Alpert Drazen: In Judaism, there is a concept called ‘Hiddur Mitzvah,’ and it means that we are beautifying the mitzvah. It’s like dressing up to go to church or to synagogue. A stained-glass window is something special. A stained-glass window is something extra. It’s beautiful.

Molly Hunken: Jewish families attended services, educated their children and became involved in the vibrant community surrounding The White Shul for decades. But, by the 1940s, much of the new generation of Sheboygan’s Jews didn’t feel as connected to Orthodox Judaism. So in 1944, the Orthodox congregations of Sheboygan were largely replaced by a new group, called Congregation Beth El, which is the only remaining synagogue in Sheboygan, and over the past few decades, Sheboygan’s Jewish population has shrunk considerably.

Jonathan Pollack is the chair of the History Department at Madison Area Technical College, and an honorary fellow of the Center for Jewish Studies at UW-Madison. He says this is a common trend.

Jonathan Pollack: Jewish families in small towns, especially, ya know, starting really in the 1920s, saw college as a great thing and something they wanted their kids to pursue for all the opportunities that a college education brought. That same education meant that a lot of people were not going back home.

Molly Hunken: Having grown up in Sheboygan, Drazen agrees.

Susie Alpert Drazen: We were not encouraged to stay. We were encouraged to go to college, make a life, and perhaps find a larger Jewish community to be part of.

Molly Hunken: Drazen and Pollack both think that unless more job opportunities arise in Sheboygan, the Jewish community will likely continue to shrink. However, pieces like the Star of David window are an important reminder of the rich history of Jewish culture in Sheboygan.

Maureen McCollum: Molly Hunken brought us that story on a Sheboygan synagogue. The building’s stained-glass window is part of the Wisconsin 101 project which tells our state’s history through objects. Wisconsin Life is a co-production of Wisconsin Public Radio and PBS-Wisconsin in partnership with Wisconsin Humanities. Additional support comes from Lowell and Mary Peterson of Appleton. I’m Maureen McCollum.

Essay by Bella Roberts

Produced for Wisconsin Life by Maureen McCollum and Molly Hunken

On the western coast of Lake Michigan sits the city of Manitowoc, Wisconsin, a place known for its deep connection with the water. And along its shore, a lighthouse essential to the area’s maritime history stands tall, watching over the city. Molly Hunken climbs inside to take us on a tour of the Manitowoc Breakwater Lighthouse.

Listen below to the segment from Wisconsin Public Radio’s Wisconsin Life.

Maureen McCollum:

On the western coast of Lake Michigan sits the city of Manitowoc, a place known for its deep connection with the water and along its shore, a lighthouse essential to the area’s maritime history stands tall watching over the city. Molly Hunken climbed inside to take us on a tour.

Paul Roekle:

Okay, well, welcome to Manitowoc North Breakwater Lighthouse. You’re about half a mile out in the lake here. Ludington is about 60 miles across the lake straight over here, so you’re out in the center of things here.

Molly Hunken:

Paul Roekle is a member of Manitowoc Sunrise Rotary, a locally based group which organizes fundraising events for the community. Within the past decade, they have also become the official caretakers of the Manitowoc North Breakwater Lighthouse. The lighthouse was built in 1918 making it over 100 years old. Its name comes from the structure that it’s built on.

Paul Roekle:

When you walk out here on the concrete, that’s the breakwater. And basically what that is, it separates the lake from the harbor, and it makes a safe place for the ships to come in and be protected.

Molly Hunken:

The building itself has five stories. Its first floor is a basement which used to act as storage and a boathouse. In this portion of the basement was a dory, a small boat which lighthouse keepers used for rescues.

Paul Roekle:

But you can read stories on it where the lighthouse keepers in its day would take care of the rescues on the lake when they occurred, and even the middle of winter in a tremendous blizzard, at night, no lights, they had to listen to the sounds and actually push the boat out, hop in it, and go out and rescue people, then bring it back in.

Molly Hunken:

On the second floor, the motor room housed the motor to generate power for the light on top. Above that, sits the watch room, where lighthouse keepers used radio equipment to keep in touch with boats out on the lake. In cases of stormy weather, sometimes lighthouse keepers stayed overnight in cots in this room, though they normally slept on shore. The diaphone room on the fourth floor used to be the location of the foghorn, also called a diaphone. Ships could activate the diaphone from the lake to warn of their arrival on shore. From the deck outside, you can see the Badger Car Ferry, which has been running since the 1950s beginning its round trip between Manitowoc and Ludington, Michigan.

Paul Roekle.

That two signals. That’s a salute to us. Thank you.

Molly Hunken:

After a brief climb up a small metal ladder, you reach what most people would think of when imagining a lighthouse, the lens house.

Paul Roekle:

That’s where the light that signals to the ships is located, and this particular light could be seen from 17 miles out in a lake.

Molly Hunken:

The small room on top of the lighthouse holds no more than the light itself, with enough space for a few people around it. The expansive view looks out over Lake Michigan and the city of Manitowoc, after the need for lighthouse keepers disappeared, the building became run down. It succumbed to vandalism and the wear and tear expected for a building in the middle of a lake. But in 2011 the Manitowoc North Breakwater Lighthouse was put on auction by the Coast Guard. It was purchased by a man from Long Island, New York named Philip Carlucci for $30,000.

Paul Roekle:

You buy a property from the Coast Guard, you have to bring it up the standards and maintain it. So he stuck over $325,000 into it, to get into the condition it is in today.

Molly Hunken:

The owner and Manitowoc Sunrise Rotary are collaborating with the Wisconsin Maritime Museum, also located in Manitowoc, to return historical objects and equipment to the building. Looking forward, the owner hopes to continue restoring the lighthouse to its original state.

Maureen McCollum:

Molly Hunken brought us that story on the Manitowoc Breakwater Lighthouse. The building itself is part of the Wisconsin 101, project which tells our state’s history through objects. Wisconsin life is a co-production of Wisconsin Public Radio and PBS Wisconsin in partnership with Wisconsin Humanities. Additional support comes from Lowell and Mary Peterson of Appleton. Find more Wisconsin life@wisconsinlife.org and on Facebook and Instagram. I’m Maureen McCollum.

Essay by Keeley Flynn

Produced for Wisconsin Life by Maureen McCollum and Molly Hunken

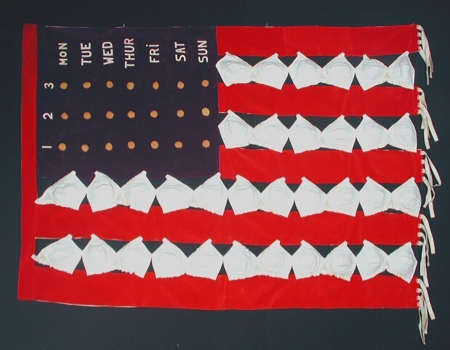

The 1970s were the height of the second wave of feminism, where women were advocating for equal rights and opportunities to men in the US. In 1971, one woman expressed her feminist views through art made out of a unique medium: bras.

Listen below to the segment from Wisconsin Public Radio’s Wisconsin Life.

Maureen McCollum: The 1970s were the height of the second wave of feminism, when women in the U.S. were advocating for equal rights and opportunities to men. As Molly Hunken tells us, it was during this time that one woman expressed her feminist views by creating art made out of a unique medium: bras.

Molly Hunken: Artist Marge Engelman has spent much of her life in Wisconsin. The walls of her Madison apartment reflect that time as they’re covered with countless art. Despite Engelman’s own works of art that currently adorn her apartment’s walls, she says she wasn’t always an artist.

Marge Engelman: When I was in grade school, a teacher had implied that I did not have artistic ability, so I took that seriously.

Molly Hunken: Engleman says that he never visited art galleries until she was 38, and she definitely didn’t make her own art. That changed when she discovered that the University of Wisconsin-Extension offered courses in contemporary art.

Marge Engelman: I found out there was a program in the School of Home Economics, and it was called Related Art. So I registered. I was about 40 years old, so I was a different kind of student.

Molly Hunken: Through this program, Engelman got her master’s degree in art after two years. She taught introductory art courses for a few years, and was then appointed as the director of outreach at UW-Green Bay. Engelman says that around this time, change was taking root.

Marge Engelman: The feminist movement came along, and I became a “flaming feminist” because I’ve felt quite a bit of discrimination growing up, and also working. Because women weren’t valued as much as men.

Molly Hunken: Engelman says she was inspired by this moment. It led her to start a childcare center on UW-Green Bay’s campus for students and faculty. Plus, she was still creating art, including a historical piece she created in 1971 that was inspired by the bra-burning feminists.

Marge Engelman: But then it was about that time I got the idea for the bra banner. And I called it the “The Land of the Freed-up Woman.”

Molly Hunken: The banner looks like the American flag, but features stripes made out of red velveteen and twenty white padded bras. It also alters the stars in the corner of the flag by replacing them with foam modeled after birth control pills.

Marge Engelman: The pill, the contraceptive pill had just come out and so I decided I could visualize that in the field of blue.

Molly Hunken: She created the flag in response to her experiences with discrimination. During her time in administration at UW-Green Bay Engelman says she was the only woman on staff.

Marge Engelman: There were things that were said to me, and opportunities I didn’t have because I was a woman, and I thought people should start thinking about that.

Molly Hunken: At the age of 96, Engelman is still creating art out of her Madison home.

Marge Engelman: I have made a sewing center here in the back, so I put my sewing machine here.

Molly Hunken: Some of her art relates to more tame themes, like nursey rhymes.

Marge Engelman: Mary had a little lamb whose fleece was white as snow.

Molly Hunken: But like the bra flag, she continues to create pieces that are politically motivated.

Maureen McCollum: Molly Hunken brought us that story on Marge Engelman’s bra flag. The art itself is part of the Wisconsin 101 project which tells our state’s history through objects. Wisconsin Life is a co-production of Wisconsin Public Radio and PBS-Wisconsin in partnership with Wisconsin Humanities. Additional support comes from Lowell and Mary Peterson of Appleton. I’m Maureen McCollum.

Essay by Anastasia Welnetz and Trase Tracanna

Produced for Wisconsin Life by Rachael Vasquez

What would a Southeastern Wisconsinite grab on a hot summer day in the 1970s and 80s? Jolly Good soda of course! This local brand was celebrated as the cornerstone of cookouts, family reunions, and get-togethers.

Listen below to the segment from Wisconsin Public Radio’s Wisconsin Life.

Maureen McCollum:

What’s the first drink you think of when you hear this sound? A Pepsi Miller Lite, or was it a jolly good soda, a drink that has its roots right here in Wisconsin, a can of Jolly good soda is one of the many items included in the Wisconsin 101 project which tells the state’s history through objects. WPR’s Rachael Vasquez visited the Jolly good plant to reintroduce us to a Midwestern favorite.

Rachael Vasquez:

If you’re having trouble remembering Jolly Good, maybe this will ring a bell:

Period Advertisement:

The next time you’re in a food store buying cola, root beer, orange, or any flavored soda, take a good look at the price. I mean, a really good look. At Jolly Good, we believe in quality, but we also believe in value. We want you to get your money’s worth.

Rachael Vasquez:

Jolly Good was beloved by Midwesterners in its heyday. Krier Foods started the brand in the 1970s in Belgium, Wisconsin, but after decades of filling fridges across the region, competition from the big soda companies edged them out. They sold the last case of Jolly Good in 2007, but then 2013 rolled around and an uncle and his nephew had an idea.

John Rassel:

The term craft became very popular in the beer industry. Was there some opportunity for us to to play off that niche?

Rachael Vasquez:

That’s John Rassel, the nephew of the pair and now the President of Krier Foods. His uncle, Bruce Krier, headed the company before him.

John Rassel:

He was the one that really propelled Jolly Good to what it was.

Rachael Vasquez:

The two talked about if they could relaunch the brand and how it would work. Soon enough, they had a shot at putting it back on store shelves.

John Rassel:

So we just decided to make a small batch and see what happens.

Rachael Vasquez:

Rassel says their first big win was getting Jolly Good into Piggly Wiggly. But before long, they were selling in retailers like Woodman’s Markets, Sendik’s, and now their latest retail partner, Festival Foods.

John Rassel:

Right now, I think we would deem it as a success.

Rachael Vasquez:

Today the company makes Jolly Good at their facility in the small community of Random Lake, about 20 miles outside of Sheboygan. They produce eight regular flavors and seven diet, including cherry, cream, and the beloved “Sour Pow’r.” Before the cans get to you, each and every one goes through a special process. First, they mix it all up in a place they call the batch room.

John Rassel:

So we have two 8,000 gallon tanks, and then two 6,000 gallon tanks. So we batch the liquid back here, and then we send it out to the filler to be put into the cans.

Rachael Vasquez:

Next some tests to make sure it’s all up to snuff, and then all of that soda and a bunch of empty cans are sent to the filler room, which always smells like whatever flavor is being filled. That machine goes very fast.

John Rassel:

Seven to eight hundred cans a minute.

Rachael Vasquez:

From there, the cans are sent over to be boxed up and shrink wrapped, and then they’re put on a pallet in a warehouse with cans that go, as far as you can see, that’s where they wait before they head out to stores across Wisconsin, along with a few places in Illinois. Even with the pandemic, Russell says Jolly Good has been doing well, but he says they’ve also got ground to make up with customers they missed when they had to stop selling.

John Rassel:

If you do the math from from 2007 to 2014 when we weren’t on the shelves, we missed a generation.

Rachael Vasquez:

Russell says they have some help with that, though, from older generations who still know and love Jolly Good.

John Rassel:

Part of it is, is that those older generations remembering the brand, remembering the memories, and wanting to recreate those memories with the younger generation. It’s very impactful, you know, especially during this time.

Rachael Vasquez:

That’s where a lot of the brand’s power comes from, the nostalgia people feel for it.

John Rassel:

Whether it was camping ball games, you know, the lake house, the beach, you know, you name it. Everyone, you know, just kind of reached out, you know. I remember drinking Jolly Good.

Rachael Vasquez:

Rassel’s uncle Bruce passed away before he had a chance to see Jolly Good come to life again. He says it was important to pay homage to him and his work building Jolly Good.

John Rassel:

Hopefully he’d be proud. I think we did a pretty good job.

Maureen McCollum:

WPR’s Rachael Vasquez brought us that story on Jolly Good soda. It’s part of the Wisconsin 101 project which tells our state’s history through objects. Wisconsin Life is a co-production of Wisconsin Public Radio and PBS Wisconsin in partnership with Wisconsin Humanities, additional support comes from Lowell and Mary Peterson of Appleton. Find more Wisconsin Life at wisconsinlife.org and on Facebook. I’m Maureen McCollum.

Essay by Nick Ostrem

Produced for Wisconsin Life by Maureen McCollum and Jane Genske

Imagine this: It’s early morning in a small Wisconsin town about a century ago. The sun hasn’t risen, but parents bustle around the kitchen. They’re making pasties.

One’s for dad, who’s preparing for a day in the mines.

Some are for the children, who are about to head to their one-room schoolhouse.

The extras are for mom, who will warm them up for dinner tonight.

Listen below to the segment from Wisconsin Public Radio’s Wisconsin Life.

Maureen McCollum: Is there really anything better than a buttery, flaky pastry filled with meat and vegetables, or perhaps just vegetables for our vegetarian friends? The pasty has long been a staple in certain Wisconsin communities and has a rich history with a particular group of workers. Jane Genske went to learn more about the role of pasties in Wisconsin history.

Jane Genske: Imagine this: it’s early morning in a small Wisconsin town about a century ago. The sun hasn’t risen, but parents bustle around the kitchen. They’re making pasties. One’s for dad, who’s preparing for a day in the mines. Some are for the children, who are about to head to their one-room schoolhouse. The extras are for mom to warm up for dinner tonight. The pasty is convenient, handheld and delicious. It’s a flaky, buttery pastry folded over, pinched at the crust, bursting with meat and vegetables. The more traditional fillings might include beef, rutabagas, onions, and potatoes.

Customer Recording: Okay, yeah, could we do two of the Greek.

Jane Genske: Joe’s Pasty Shop has been making these savory pies for decades. Jessica Lapachin opened a location in Rhinelander 15 years ago. She talks about the business’s history while her husband, Larry, chops onions.

Jessica Lapachin: So Joe’s Pasty Shop is a third-generation pasty business. My family opened up Joe’s Pasty Shop in Ironwood, Michigan in 1946

Jane Genske: Miners from Cornwall, England flocked to Wisconsin in the 1800s. They settled in places like Mineral Point and Miners Grove as more lead was needed for things like paint, pipes, and lead shot. Cornish miners brought their mining expertise for extracting Galena, which is a mineral used to make lead. They also brought a piece of their European culture, the pasty.

Jessica Lapachin: It’s a portable meal that the Cornish miners would have taken down into the mine, a handheld meal that they could hold with dirty hands. And they would hang onto the crimp of the crust, eat the center and throw the crimp away.

Jane Genske: While the pasties kept the miners nourished, they also thought the scraps could bring them good luck.

Jessica Lapachin: So there’s a superstition in mining culture of these spirits that live in the mine. They’re called Tommy Knockers. And so they would do things like move tools around or hide things from the miners. And so, you know, the miners started to think, well, we have to appease them. Let’s give them the crust of our pasties. So they would toss that into the corners of the mine. So…

Jane Genske: When the demand for lead decreased in southwestern Wisconsin, many Cornish miners moved to the Upper Peninsula to work in copper and iron mines. Pasties became a family tradition passed on from generation to generation. Lapachin says hers isn’t the only family with a pasty story.

Jessica Lapachin: And it’s a very familiar, memorable food for people. People are really passionate about their favorite pasty and their pasty stories and the way their grandmother made them.

Jane Genske: Inside Joe’s is regular customer, LJ Summers. He didn’t grow up with pasties, and had his first one when he moved to Rhinelander.

LJ Summers: In the past year, since I’ve lived in the neighborhood, and everybody was like, “You need to go get a pasty.” And so I did, and I’ve been hooked ever since.

Jane Genske: Summers is now a pasty fanatic. He can’t stay away from the shop for more than a week.

LJ Summers: Well, I like the Greek pasty a lot. That’s definitely my favorite. And then my new favorite recently is the Cornish one, because that one goes unannounced, like, I feel like nobody pays attention to it because of the rutabagas. People are scared of rutabagas.

Jane Genske: Even after the fall of the mining era in Wisconsin, people’s love of pasties lives on.

Maureen McCollum: That story about pasties in Wisconsin came from Jane Genske. She’s a UW-Madison student working on an internship for Wisconsin Life and Wisconsin 101 which tells the history of the state through objects. Wisconsin Life is a co-production of Wisconsin Public Radio and PBS Wisconsin, in partnership with the Wisconsin Humanities Council. Additional support comes from Lowell and Mary Peterson of Appleton. Want to make sure you catch every Wisconsin Life story? Subscribe to our podcast feed and find more Wisconsin Life at wisconsinlife.org and on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. I’m Maureen McCollum.

Essay by Julie Hein

Produced for Wisconsin Life by Maureen McCollum and Jane Genske

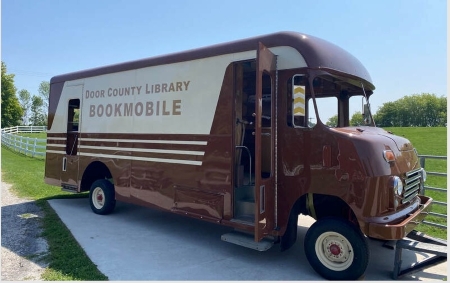

In 1950 when the Door-Kewaunee Regional Library Demonstration first brought bookmobiles to the Door Peninsula, nearly 23% of Wisconsinites did not have access to a free library. With many remote towns and islands, a low overall population, poor transportation, and low literacy rates, the Door Peninsula offered an opportunity to test the bookmobile model for extending rural library services.

Listen below to the segment from Wisconsin Public Radio’s Wisconsin Life.

Maureen McCollum:

Bookmobiles have long dotted Wisconsin’s roadways and parking lots. The state has a history of bringing books and movies to the people living anywhere from the Wisconsin Dells to Green Bay, the historic Door County bookmobile is one of the many items included in the Wisconsin 101, project which tells the state’s history through objects. Jane Genske, went to learn more about the role that bookmobiles play in our communities.

Jane Genske:

On a hot summer day on the north side of Madison, families shuffle in and out of the dream bus. It’s a bookmobile with bright cartoons painted on the outside.

Amy Winkleman:

This is a public library on wheels. So we have books, we have DVDs, we have CDs, we have audio books.

Jane Genske:

That’s Amy Winkelman, a librarian on the dream bus.

Amy Winkleman:

The idea is to bring library service to people that may otherwise, for whatever reason, have trouble getting to a library branch. So we built the top with his information. For his part, this is a big outreach project. We we want everyone to know that. We want them to be able to be able to use that public library service.

Jane Genske:

The bus can hold around 2500 books on its specially tilted shelves so they don’t fall off. The librarians are sure to stock the appropriate books for each of the stops in Madison and Sun Prairie, readers can find anything from foreign language materials to children’s books, plus the librarians take special requests. It’s a really fun way to get people excited about library service. The Dream bus is one of the many bookmobiles in Wisconsin. The state has a rich history of bookmobiles serving communities, especially in rural places like Door County.

The Door County bookmobile was a traveling public library that brought an array of books to the peninsula in the 1950s only the area’s wealthy families had large book collections, or those living near larger cities, like Sturgeon Bay had access to books. Students in rural schools were underperforming in reading and writing. Farmers worked all day at the expense of reading time. Many schoolhouses in Door County only had about 15 books on their shelves. Michaela Kraft is an intern at the Egg Harbor Historical Society. She has been researching the function of the bookmobile and its legacy for Door County today.

Michaela Kraft:

So the bookmobile actually was founded out of a need here in Door County, especially for rural readers,

Jane Genske:

The state funded the bookmobile in Door County and Kewaunee county in the 1950s. It was then up to the residents to decide if they wanted to continue funding it with tax dollars.

Michaela Kraft:

And then in 1952 they voted Kewaunee and Door County, and only Door County kept the bookmobile service.

Jane Genske:

This led to increased literacy scores for children living in the area.

Michaela Kraft:

It was actually instrumental in a lot of the older generation now loving reading.

Jane Genske:

The bookmobile would travel all over the peninsula. It stopped at churches, schoolhouses and street corners. For many children and adults, it was a chance to learn anything from new languages, to farming to home improvement tips.

Michaela Kraft:

The school children would look forward to the bookmobile because it would come once a week and they could choose anything.

Jane Genske:

The bookmobile brought excitement and curiosity to Door County. It opened the world to small communities who otherwise wouldn’t know what was going on beyond the peninsula.

Michaela Kraft:

I think before the bookmobile, a lot of children, especially, weren’t even aware of print culture or the opportunities that they could discover outside of their county, because they were so exceedingly rural. And there were a lot of immigrants who a lot of times, wouldn’t even speak English outside the home, even, so they would only have that experience of the outside world through reading.

Jane Genske:

In addition to increased literacy scores and eye opening experiences for isolated residents, it also provided a sense of interconnectedness amongst the scattered communities in Door County, much like the bookmobiles continue to do today.

Maureen McCollum:

That story about bookmobiles came from Jane Gensky, a UW Madison student working on an internship for Wisconsin Life and Wisconsin 101 which tells the history of the state through objects. Wisconsin Life is a co-production of Wisconsin Public Radio and Wisconsin Public Television in partnership with the Wisconsin Humanities Council. Additional support comes from Lowell and Mary Peterson of Appleton. Find more Wisconsin Life at wisconsinlife.org and on Facebook. I’m Maureen McCollum.

Essay by Elizabeth Matelski

Produced for Wisconsin Life by Erika Janik and Ellie Gettinger

Practical, economical, reliable: the unlikely origins of a hundred-year-old cookbook that still graces kitchens across America.

Listen below to the segment from Wisconsin Public Radio’s Wisconsin Life.

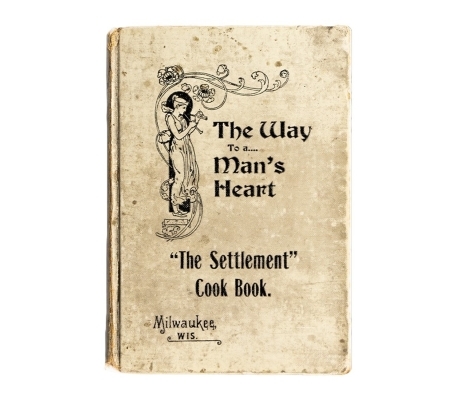

Erika Janik: Before Martha Stewart and Julia Child, there was Lizzie Kander. Ellie Gettinger from the Milwaukee Jewish Museum, tells us about the settlement cookbook and the remarkable woman behind its creation.

Ellie Gettinger: The settlement cookbook was something that I’d heard of. I grew up in Tennessee. We had one in my house, but I had no idea the history. It just was a cookbook. And I think like many people in the United States, my assumption was that the settlement house, if it was a place, was in New York. The settlement house movement in Milwaukee was founded by these German-Jewish immigrants who were looking at these new poor, Russian and Eastern European immigrants and thinking, we’ve worked really hard to be, you know, to fit in in Milwaukee. And there was this real fear that these new poor immigrants would reflect badly on the existing Jewish population that was primarily German speaking. So in the 1890s they start this as a way of developing programs.

And Lizzie is a really interesting woman. She was born in the United States. Her parents were German immigrants, and Lizzie actually went to high school in the 1870s in Milwaukee, which is not, most girls aren’t getting that kind of advanced education. And so when she graduates high school, she actually is elected valedictorian in 1878 and the title of her valedictorian address is “When I Become President.” And so after she graduates, though, that’s it, you know, she’s not going to college. And the role of a woman at that point, an upper-class woman, is that you get involved in good works. And she got married, she never had children, and so she then had all of this time to think about what she should be doing in her city.

So she starts the organization. She recruits the people. She hires the staff. In like 1898 one of the things she initiates is a cooking class, and she has this sense that she’s going to teach them how to be economical American housewives. It’s not necessarily Americanizing them in the way that you think, like apple pie. You will find recipes for lots of German dishes because she is teaching them how to cook like her, an upper class German-Jewish lady. The first cookbook is published in 1901 and the impetus at first is her students are copying down recipes by hand, and it’s taking a long time, and it’s not efficient. And the other thing is that if you have something that’s published, it has more authority than something that is handwritten. And she goes to her board of directors, all men that she’s recruited, and says, I’d like to publish this cookbook. I need $18 and they immediately say, “No, we don’t think we can spare that expense, but if you find somebody to fund it, we’d be happy to share in your proceeds.” Very generous of them. So she goes to the publisher, and they develop a system where they go to most of the German-Jewish business people in the city, and they sell advertising for the cookbook. And that’s how they get their initial investment of $18 and they do a run of 1,000. They sell it for 50 cents a piece at the Boston Store.

So they sell out, but it was never the sense of, ‘this was a one time thing,’ she saw how successful this was, and immediately starts editing it. By 1907 they do their third edition, and this is really the point when it goes from being a Milwaukee regional cookbook to a national entity. You know, there are very few books that were written in Wisconsin that have the national reach that this one does. Like this is something that could have been so local, and that these women had this vision of, you know, we can take this and make this a national product.

Erika Janik: This story was produced in partnership with Wisconsin 101, a statewide collaborative project to share Wisconsin’s story in objects. Wisconsin Life is a co-production of Wisconsin Public Radio and Wisconsin Public Television in partnership with the Wisconsin Humanities Council. Additional support comes from Lowell and Mary Peterson of Appleton. Find more Wisconsin Life on our website, wisconsinlife.org and on Facebook. I’m Erika Janik.

Essay by Sam Gee

Produced for Wisconsin Life by Jane Genske

They don’t call Wisconsin “America’s Dairyland” for nothing. The Babcock ice cream carton symbolizes both Wisconsin’s dairy farming past and its appeal as a summer destination for tourists from around the world.

Listen below to the segment from Wisconsin Public Radio’s Wisconsin Life.

Maureen McCollum:

When you see a carton of ice cream from Babcock Hall dairy plant, you’ll notice it’s not particularly flashy. It’s red, white and black. Bucky Badger appears next to a sticker that tells you the flavor. Maybe it’s blue moon orange custard, chocolate chip or Mocha macchiato. But does it really matter what the carton looks like? As the cliche goes, it’s what’s inside that counts, the Babcock ice cream carton is one of the many items included in the Wisconsin 101 project which tells the state’s history through objects. Jane Genske visited the Babcock plant to learn more about the importance of the beloved ice cream.

Jane Genske:

The Babcock dairy store on UW Madison’s campus is a place you can find one of Wisconsin’s most treasured ice creams. Glenda Jones is an employee at the dairy store. She loves selling and eating Babcock ice cream, and has been doing it for 16 years.

Glenda Jones:

And my favorite ice cream is chocolate peanut butter.

Jane Genske

Students, faculty and ice cream lovers crave Babcock ice cream to the point where they will drive from across the state to buy a gallon of their favorite flavor. Babcock dairy plant supervisor Raymond Van Cleve explains this phenomenon.

Raymond Van Cleve:

We’ve got people all the way from northern Wisconsin that drive down and pick up ice cream in the summertime, you know, once, once a week, you know, they come down big ice cream coolers and stuff, and pick up ice cream and take it back up north. So, but yeah, it’s always good to hear stories about people that come in, you know, and say, Babcock. We gotta have Babcock.

Jane Genske:

Inside the dairy plant, students studying food science can be found making ice cream and cheese.

Raymond Van Cleve:

First and foremost, we’re an educational facility.

Jane Genske:

Van Cleve says, UW Madison isn’t looking to get rich off of Babcock ice cream, cheese and milk. They simply want to educate students and advise nearby small farms and dairy factories. The ice cream’s recipe was created in the 1950s and hasn’t changed since. And this plant looks a lot like how it did when it opened in 1951. It’s filled with large metal vats of milk, pasteurizers and ice cream churning tanks.

Raymond Van Cleve:

I believe this is pretty close to the footprint of what everything was originally. Yeah, a lot of this place hasn’t really been remodeled or hasn’t been re touched with a lot of things since then. Some of these pieces of equipment are 50/60, years old,

Jane Genske:

Although Babcock isn’t the largest dairy plant their history is among the oldest, starting in the late 1800s. Babcock plant gets its name from UW Madison Professor Stephen Babcock, who helped develop the first butterfat test in 1890. With the butterfat test, consumers knew that the milk they purchased was high quality and safe to drink. UW Food Science Professor Emeritus Robert Bradley says the butterfat test revolutionized the dairy industry.

Robert Bradley:

This is Babcock Hall, and his first centrifuge is down in the front lobby, if you wanted to take a look at that. And the centrifuges is a means of of putting the denser product on the bottom and the lighter product on the top, which would be the fat column.

Jane Genske:

And Bradley says Babcock ice cream is on the denser side.

Robert Bradley:

It’s a top quality ice cream. We haven’t cut corners.

Jane Genske:

Because of Babcock’s invention, Wisconsin not only became known as America’s Dairyland, but helped his namesake ice cream become iconic.

Maureen McCollum:

That story about Babcock ice cream came from Jane Genske, a UW Madison student working on an internship this summer for Wisconsin life and Wisconsin 101 which tells the history of the state through objects. Hey Wisconsin life fans, we are giving our website a facelift, and we’d love to hear from you how we can make it better. Send us an email to wisconsinlife@wpr.org to let us know if you’d like to share your thoughts on our website. That’s wisconsinlife@wpr.org Wisconsin Life is a co-production of Wisconsin Public Radio and Wisconsin Public Television in partnership with the Wisconsin Humanities Council. Additional support comes from Lowell and Mary Peterson of Appleton. Want to make sure you catch every single Wisconsin life story. Subscribe to our podcast feed and find more Wisconsin life@wisconsinlife.org and on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. I’m Maureen McCollum.

Essay by Ben Clark

Produced for Wisconsin Life by Erika Janik and Ben Clark

Five brothers from Hamburg, Wisconsin, built a fox-fur empire that transformed the fur industry and played a major role in the development of a canine distemper vaccine.

Listen below to the segment from Wisconsin Public Radio’s Wisconsin Life.

Erika Janik:

Before I moved to Wisconsin, my grandma offered me her silver fox fur coat for Midwest winters. I declined, but I’ve been regretting my decision ever since I talked to Ben Clark from the Marathon County Historical Society about the Fromm brothers and their world famous silver furs.

Ben Clark:

When you say fur trade, people think of the Beaver and the people coming down the river and canoes to trade with the Native Americans and the that’s why we have places like Green Bay and La Crosse, you know, they were trading posts that then grew into cities. And this is an entirely, it’s a related but it’s completely separate fur trade. So the one we went with, it’s a fur coat made out of silver fox fur, probably produced in the early ’40s, and this was after 1934 the height of fashion in the United States.

The Fromm brothers themselves, their mother was, her maiden name was Nieman, and when he she married Frederick Fromm, a dairy farmer in the area, her parents gave her a tract of land in Hamburg, Wisconsin, and that became the Fromm farm. Frederick and Alwina Fromm ended up having nine children, and it’s the youngest four sons that then kind of take over the Fromm farm. And they became kind of interested in fox fur, because a good fox fur could, you know, you could sell it for a couple dollars and help support your family.

The red fox is is actually the same species as the silver fox. So you can actually breed the foxes to create certain characteristics, primarily as the color. If you can produce that quality of pelt that could that color of fur on a farm, well, then you’d be set. So the Fromm brothers heard about this, and they kind of decided, well, this is what we want to do with our lives. So they were experimenting with Fox farming in the first decade of the 20th century. One of their goals was to just grow as many foxes as possible. The Silver Fox was not particularly popular, but you know, as time goes on, as the market did switch in 1934 they were sitting on the largest supply of silver foxes in the world. Everybody wanted the silver. And everybody who had been breeding for years towards the other direction, were now scrambling, and it would take years for them to get, you know, eliminate that dark color and get back to what the Fromms were doing.

So they had a period where they were, you know, they had a lot of influence in the industry, and they kind of considered it and thought, you know, what should we do about this? And one of the things they didn’t like was the auction system. So they decided, you know, why don’t we just hold our own auction? Everybody wants our pelts and well, just see what happens. And so they put out a call. They invited all of these fur buyers from across the country. So many people came from the New York area that they chartered a train, specifically from Central Station to Wausau. It lasted until 1939. This is kind of when they start getting into making fur coats themselves. By this point, the Fromms weren’t completely, you know, they didn’t have a monopoly anymore. There was competition, and the prices that they were going for were just not even rock bottom. They were just like, not at all what they were worth.

Well, I think it’s interesting, because I think when we talk about Wisconsin, obviously agriculture, farming is a huge part of the demographics and the history of our state, and I think they represent an interesting aspect in that they’re not dairy farmers. And so I think it’s interesting because the Fromms represent an aspect of that part of our economy, a part of our culture that, you know, we don’t often get to see.

Erika Janik:

This story is part of Wisconsin 101, a collaborative effort to share Wisconsin’s story in objects. Wisconsin Life is a co-production of Wisconsin Public Radio and Wisconsin Public Television, in partnership with the Wisconsin Humanities Council. Additional support comes from Lowell and Mary Peterson of Appleton. Find more Wisconsin Life on our website, wisconsinlife.org and on Facebook. I’m Erika Janik.

Essay by Joe Hermolin

Produced for Wisconsin Life by Erika Janik and Joe Hermolin

Hewn from Northwoods maple, this Vulcan Corporation pin reminds us that Milwaukee was once the bowling capital of America. From Wisconsin’s lumbering heyday, to Japan’s abandoned alleys, explore history in the bowling lane.

Listen below to the segment from Wisconsin Public Radio’s Wisconsin Life.

Erika Janik: Bowling may be the sport that made Milwaukee famous, but it was another Wisconsin town that supplied a key ingredient to the sport. Joe Hermolin from the Langlade County Historical Society brings us the story of the Vulcan bowling pin.

Joe Hermolin: Well, the object we have here is a regulation-size bowling pin. It was made in the late-1950s after Vulcan introduced its new, patented Nyl-Tuf Supreme Coating. It was intended to prolong the life of bowling pins from the beating that they took. The choice of wood, pin dimensions, coating, was determined by the American Bowling Congress, which for many years, was based in Milwaukee.

I bowl. I have bowled as a social activity. I never really took it all that seriously. But what really interested me was the story of the Vulcan Company and how it adapted to changing markets, because they came to Antigo to make shoe lasts, and then it evolved into a bowling pin factory. So I was interested, how do you get from one product to another?

The company, first of all, it started out in Ohio, and they made wooden shoe lasts. In 1919, they moved to Crandon, Wisconsin, because of an ample supply of maple wood. And then in 1925 they moved a little bit down the road to Antigo. Antigo also had an ample supply of maple trees. It was also a major railroad hub, and in those days, freight and people all traveled by rail. So Antigo, in a way, was uniquely positioned for a company that wanted to make shoe lasts. They had the raw materials and they had the means of shipping. So that’s where the companies settled in. Starting in the 1940s, the demand decreased, and so they they were looking for other products, and they tried their luck making gun stocks, golf clubs, furniture parts, sewing machine tops, shuffle boards, and wooden high heels for women’s shoes. They did get a contract to make a sort of rough cut bowling pin for Brunswick, which was a major bowling pin manufacturer, and then they decided to get into the bowling pin business themselves.

Period Advertisement: Twenty million men women and children in America are regular bowlers. They make the game our country’s most popular participating sport.

Joe Hermolin: After World War Two, bowling really took off, and automatic pin setters became popular, and the pins really took a beating. So that’s when they came up with a coating. And in 1959, they finally got approval by the American Bowling Congress, and within 10 weeks, they produced their 50,000th pin. Bowling went through same kind of in the first half of the 20th century that many other American kind of activities went through. At first, tournaments were for teams consisting of white males, and eventually, it took a little push, but the American Bowling Congress recognized African American teams, minority teams, women’s teams, into the fold of these bowling tournaments. In the 1950s, as more and more American homes became equipped with television, bowling tournaments on television became very popular. Milwaukee, its program called Bowling with the Champions, was one of their more popular TV shows. So in a way, all these little things about bowling reflect just the evolution of social norms within the country.

Erika Janik: This story was produced with Wisconsin 101. Wisconsin Life is a co-production of Wisconsin Public Radio and Wisconsin Public Television in partnership with the Wisconsin Humanities Council. Additional support comes from Lowell and Mary Peterson of Appleton. Find more Wisconsin life on our website, wisconsinlife.org and on Facebook. I’m Erika Janik.

Essay by Thomas Rademacher

Produced for Wisconsin Life by Erika Janik and Thomas Rademacher

Wisconsin went crazy for bicycling in the late 19th century. Hailed as “the most independent, healthful, rapid, and convenient mode of travel” in the 1890s, Wisconsinites not only rode bikes, they made them.

Listen below to the segment from Wisconsin Public Radio’s Wisconsin Life.

Erika Janik: Bicycling in Wisconsin in the 1890s was called the most independent, healthful, rapid, and convenient mode of travel. As part of our ongoing look at objects from Wisconsin’s past. Tom Rademacher tells us about the Kenosha made Sterling Safety Bicycle.

Tom Rademacher: Cycling in the 1890s was predominantly a male activity, however, this bicycle allowed women to also engage in the recreational sport of cycling. Sterling Safety Bicycle. It was manufactured in 1899 by the American Bicycle Company. It has a lower top tube which accommodated the fashionable dresses at the time for women, so that women could also go on rides.

Bicycles entered into the United States in 1869 on the east coast from Europe, and then pretty much just steadily moved westward. And by 1880, there was a national association for bicycling called the League of American Wheelmen, which was founded on the east coast, but Wisconsin had a Wisconsin State Division, and then there were about 40 local club divisions within Wisconsin. Wisconsin, at its peak, was ranked eighth in membership and one of the leading divisions of the West.

The wheelmen, the bicyclists of the 1890s called themselves wheelmen, so the wheelmen of the 1890s created promotional materials like handbooks, maps, and things like that, which enabled cyclists of that era to link up with other clubs in the area, find the best roads for cycling, and avoid the worst ones, because most roads in the 1890s were just mud and dirt trails unless you were in a large city like Milwaukee, and so it was oftentimes difficult to actually enjoy the sport on the poor roads. And they would publish pamphlets and materials trying to promote the need for better roads, but they also tried to get people like farmers on board and advocated for farmers, trying to get them to understand that a better road will help get their produce to market.

Period Advertisement: Where there’s a wheel, there’s a way. But with bicycles, the way has been rather torturous. There were no traffic signals in those rollicking days.

Tom Rademacher: Interestingly, the company actually switched from manufacturing bicycles to then automobiles at the turn of the century, once the bicycle boom ended. And this is just a reflection of how quickly the decline of bicycling happened, and show us the start of the rise of automobiles as being a premier mode of transportation.

I’m a big fan of cycling, and I wanted to learn more about the history of biking in Wisconsin. The part that interests me the most about the safety bike and the movement is the interesting connections that can be seen in the 1890s as well as to today, because a lot of the materials that the wheelman published in the 1890s are things like maps and route materials and listings of bike shops and hotels for people to travel to, and that’s the same kind of material that organizations will put out today for their members. It’s over a century ago, but yet we can still do the same kinds of things today.

Erika Janik: That story was produced in partnership with Wisconsin 101, a collaborative effort to share Wisconsin story and objects. Wisconsin Life is a co-production of Wisconsin Public Radio and Wisconsin Public Television in partnership with the Wisconsin Humanities Council. Additional support comes from Lowell and Mary Peterson of Appleton. Find more Wisconsin life on our website, wisconsinlife.org and on Facebook. I’m Erika Janik.

Essay by David Driscoll

Produced for Wisconsin Life by Erika Janik and David Driscoll

Awarded to six Milwaukee rescue boat volunteers in 1875, this medal is a reminder of the history of risk and heroism along Wisconsin’s shores.

Listen below to the segment from Wisconsin Public Radio’s Wisconsin Life.

Erika Janik:

Wisconsin has more than 800 miles of Great Lake shoreline. Since the early 19th century, Wisconsin’s maritime communities have routinely faced storms that could destroy businesses, towns, and lives. Wisconsin Historical Museum curator Dave Driscoll brings us the story of a lifesaving medal given for bravery in the face of disaster.

Dave Driscoll:

This is a silver medal. It’s about two and a half inches in diameter. Around the border, it says ‘Lifesaving Medal of the Second Class, United States of America.’ The back side says, ‘In testimony of heroic deeds in saving life from the perils of the sea.’ And then inscribed in the center of it is “N.A. Peterson, Wreck of the barque Tanner, Lake Michigan, September 9, 1875.’

N.A. Peterson was a ship captain who happened to be in Milwaukee. He lived in Milwaukee, but he was in Milwaukee on the night of the storm and participated in a rescue that saved the lives of eight crew members of the barque Tanner. The ship left Chicago on the evening of September 9, had a full cargo of grain, and it was heading towards Buffalo, New York. The accounts say that a squall kind of came in and knocked out a couple of its sails, and that was followed by a storm shortly thereafter, but the loss of the sails meant that the ship could not navigate when the storm arrived. It happened to be off of Milwaukee when the storm hit later that evening, folks on shore realized that the Tanner was in trouble, and there were a couple of steam tugboats that tried, on three separate occasions to connect to the Tanner and pull her to safety. And either the ropes weren’t strong enough, or the winds were too high, or in any case, at a certain point, they kind of gave up, and the ship dropped anchor in the outer harbor and just hoped for the best. A group of, you might call them watermen, the people connected with shipping or ship building, kind of put their heads together and figured out a fairly ingenious rescue method. And as a result, all six of the sailors all received life saving medals second class, which was the second such incident after the medals were instituted in 1874.

I was surprised that this happened in Milwaukee. You know, I was expecting Door County or, you know, Lake Superior, Edmund Fitzgerald sort of thing. So I guess it, it struck me that, you know, how close to shore, all this nautical stuff, how closely connected sort of Lake and shore are, in many cases, it kind of addresses the issue of of heroism. And that’s something that doesn’t show up in museum collections in an obvious way, very often, I think often with with objects, you learn about a lot of the functional things, but in this case, you know life saving, putting your life in danger in order to save someone else’s, that level of meaning and emotional content is much higher there, and I think, easier to access. It just reminds us how much Wisconsin has depended on the lakes for commerce, for sustenance, for news, for immigrants. There have been many, many people who have earned their livelihoods from the lakes, and it wasn’t always easy and it wasn’t always safe.

Erika Janik:

This story was part of Wisconsin 101 a collaborative effort to share Wisconsin story and objects. Wisconsin Life is a co-production of Wisconsin Public Radio and Wisconsin Public Television, in partnership with the Wisconsin Humanities Council. Additional support comes from Lowell and Mary Peterson of Appleton. Find more Wisconsin Life on our website, wisconsinlife.org and on Facebook. I’m Erika Janik.

Essay by Maria Serrano

Produced for Wisconsin Life by Gil Halsted

On April 5, 1860, as tensions over slavery grew, Wisconsin Congressman John F. Potter was challenged to a duel by a pro-slavery colleague from Virginia. The argument led to a 31-pound, 6-foot-long folding knife and a story that made Potter famous.

Listen below to the segment from Wisconsin Public Radio’s Wisconsin Life.

It was April 5th of 1860. Just a year before the Civil War would begin. On the floor of Congress, Illinois Congressman Owen Lovejoy was gesticulating wildly as he delivered a blistering attack on slavery. Nearly a century later, historian William Hesseltine described the scene:

“Up jumped Virginia Congressman Roger Pryor and shook his fist in Lovejoy’s face while other pro slavery congressmen shouted out derisive comments like “Negro thief!” and “The meanest negro in the south is your superior.” Republicans on the other side of the aisle rose in defence of Lovejoy’s abolitionist speech. Among them Wisconsin’s John Fox Potter of Walworth county, his great black moustache bristling.”

The debate ended peacefully as Potter remembers it with Lovejoy finishing his speech from Clerk’s desk.

A few days later, Roger Pryor challenged John Fox Potter to a duel. He claimed Potter had tampered with the Congressional record by inserting language that was not part of the debate. Here’s how Potter remembered it in an interview he gave to the Chicago Tribune in 1896:

“That afternoon I got a note from Pryor challenging me to meet him in mortal combat. I believe that Pryor’s object in proposing a duel was to obtain an easy and cheap renown in his own section. I thought after all that had taken place it was not my duty to decline to fight. But I was not a good shot with a pistol and I did not purpose to have any hair trigger business. I proposed to bring the combat down to the first principles of human butchery. Therefore I accepted his challenge with the stipulation the weapons should be bowie knives and the encounter should take place in a closed room and the fight to go on till one or the other of us fell. Pryor refused on the grounds that the terms were barbarous.’ I replied that the custom of duelling itself was barbarous and inhuman.”

The duel never happened. District of Columbia police arrested both men to keep the peace and then released them on bond after tempers had cooled. But the event, according to historian Hesseltine, made Potter famous for his willingness to defy southern braggadocio.

“From all parts of the country, bowie knives came to Representative Potter,”wrote Hesseltine. “And the following month, the Missouri delegation to the Republican convention in Chicago carried a 7-foot bowie knife to present to the redoubtable champion of northern honour.”

To add insult to the already injured southern pride, the knife was inscribed with a pun that made fun of the Virginian Roger Pryor. It read, “to John Fox Potter who will always meet a Pryor engagement.” Potter was re-elected to another term and was known for the rest of his life as “Bowie Knife Potter.” Journalists dubbed it the “Monster knife” and it became a powerful symbol of northern opposition to slavery in the 1860s.

“We all felt that the time had come for some Northern man to lay aside this scruples and strike one blow that would convince the south that we were not to be bullied any longer,“ remembered Potter.

A year later the duel with bowie knives that never happened erupted into real shooting match with the outbreak of the Civil War.

Employers Mutual Audiometer

Essay by Ben Clark

Produced for Wisconsin Life by Erika Janik and Ben Clark

Founded in Wausau, WI, in 1911, America’s first workers compensation insurance company started using equipment like the Employers Mutual Audiometer to develop new standards of workplace safety.

Listen below to the segment on Wisconsin Public Radio’s Wisconsin Life:

Erika Janik:

Employers Mutual was the first workers compensation insurance company in the United States. Ben Clark tells us about the company’s innovative test for workplace noise levels as part of Wisconsin 101.

Ben Clark:

The audiometer. It’s not a very big box, it’s not very heavy, and on the front it’s stenciled, Employers Mutual of Wausau in white letters. But I think the audiometer was interesting because it is, it’s maybe a little bit more relatable. I think most people today have gone through the process of having their hearing tested with an audiometer at some point.

Employers Mutual was founded in response to an really important law that was passed, the Workers Compensation Insurance Law of 1911. The law itself was the first workers compensation legislation to be passed in the United States, the first constitutionally upheld law. Before the law passed, there really wasn’t a system for getting workers compensation at all. If you got hurt at work, you really didn’t have a lot of recourse. You basically, you were replaceable. There wasn’t even really any protections for safety or any sort of regulations at the time. So if you got hurt, the only way that you really could get any compensation from your employer would be to take them to court and to sue them for negligence.

And so in Wausau, there was a group of investors, loosely called the Wausau Group, the sort of guys who had come to Wausau back in the 1800s and had gotten rich off of owning the lumber mills and lumber companies and all of that, and they made a decision to stick around in Wausau, even as the lumber industry was suffering because we had cut down all the big trees. They built a bunch of different really successful companies. When the law passed, they kind of recognized that this is the way that things were going to head. And so they formed Employers Mutual to write policies under the new law for their companies. Some of the very first hires were experts that would go out and consult on basic workplace hygiene or first aid and simple things. In the ’20s, it was the things they were worried about were a little bit more obvious, you know, not having loose clothing that’s going to get caught in a machine and rip your arm off. If you think about the business model of a company that does workers compensation, it makes sense to invest in outreach to make sure that people are safer at work.

Period Advertisement:

When you run a business, you expect a certain amount of the property damage. At Employers of Wausau, it’s our job as your business insurance partner to help you keep your costs down.

Ben Clark:

1953. That’s the year when there’s a court case that established that hearing loss could be something you could claim in workers compensation in Wisconsin, at least. And that was sort of the first time, and it’s kind of interesting that it takes that long. And there’s a bunch of reasons for it. I think part of it is it’s not something that’s noticeable. If you, you know, break your arm or something like that, it’s, it’s pretty clear that you, it happens in an instant. If you don’t put headphones on or your hearing protection for five minutes, you’re probably not going to lose your hearing. You know, most people don’t recognize, well, this amount of noise that I’m experiencing right now is 5/10 more decibels, than I need, I should be safely exposed to.

Employers Mutual was this national company and had branches all over but they remained headquartered in Wausau, and even though they had employees all over the place. A lot of the policy decisions were very much created by people who lived here, people based in Wisconsin. So with the hearing it took Wisconsin making the decision that hearing loss was something you could get workers compensation for, and that became the thing that caused Employers Mutual to invest and and really look at how to reduce hearing loss in the workplace.

Erika Janik: