When you think of tourism, you might think of far-away places, tropical beaches, or bustling cities – or maybe, the lakes and woods of Wisconsin. Over centuries, Wisconsin’s natural elements and landscape have drawn visitors from near and far to enjoy recreational activities throughout the state, like fishing, skiing, and bicycling. From the springs of Waukesha to the lakes of the Northwoods, Wisconsin has become a recreational escape for tourists over the years. Both public and private promotion have supplemented the attractiveness of Wisconsin’s natural landscape as local businesses and state agencies have sought to appeal to visitors and cultivate the landscape of recreation. Meanwhile, developments in transportation have shaped how and where people visit, play, and stay in Wisconsin. Through travel by rail, trail, or highway, tourists could reach destinations across the state. Tourism remains an important industry in Wisconsin today, and many people still retreat to Wisconsin’s natural areas to enjoy recreation and fresh air.

Nature and Tourism in Wisconsin

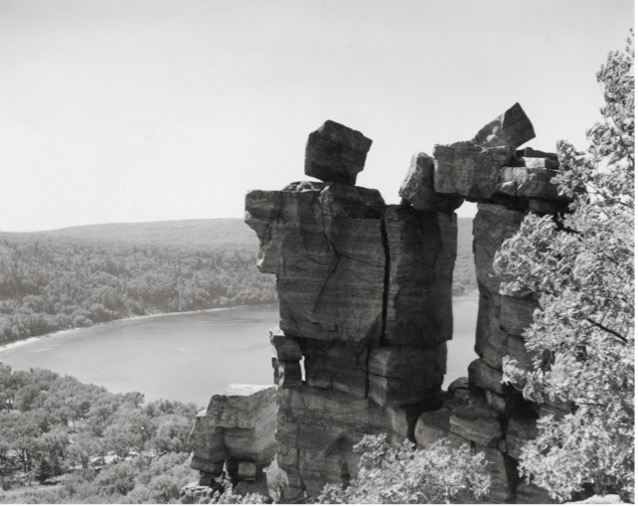

Wisconsin boasts a diverse physical geography. Many of today’s landforms were sculpted by glaciers about 13,000 years ago. The southwestern quarter of the state, however, went untouched, leaving unique formations across the “Driftless area,” like Devil’s Lake and the Wisconsin Dells. Across the Wisconsin region, prairies, forests, and valleys abound, while waterways flow from the northern highlands to the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River.

For thousands of years, the land has been inhabited by humans, including the ancestors of today’s diverse Native American population. To the Native people of Wisconsin, the natural world is sacred, reflected in the ways they use the land and regard it. The landscape and certain natural sites in the region had unique importance and did not need improvement.

In contrast, the white people who displaced them had a more utilitarian vision, using the land for economic and industrial benefit, often at the cost of degradation of natural resources. People began to idealize, appreciate, and move to preserve the natural environment as development advanced. Nature offered a distinct escape from urban settings. The natural beauty of Wisconsin began to draw visitors to marvel and enjoy the unique landscape in the mid-19th century, as more people lived in industrial cities and romanticized the natural landscape.

Tourism industries later emerged to promote recreation and leisure and serve the needs of travelers, and it continues to be important today. In the land of 15,000 lakes, there is no shortage of nature to explore and experience.

The Making of “Vacation-Land”

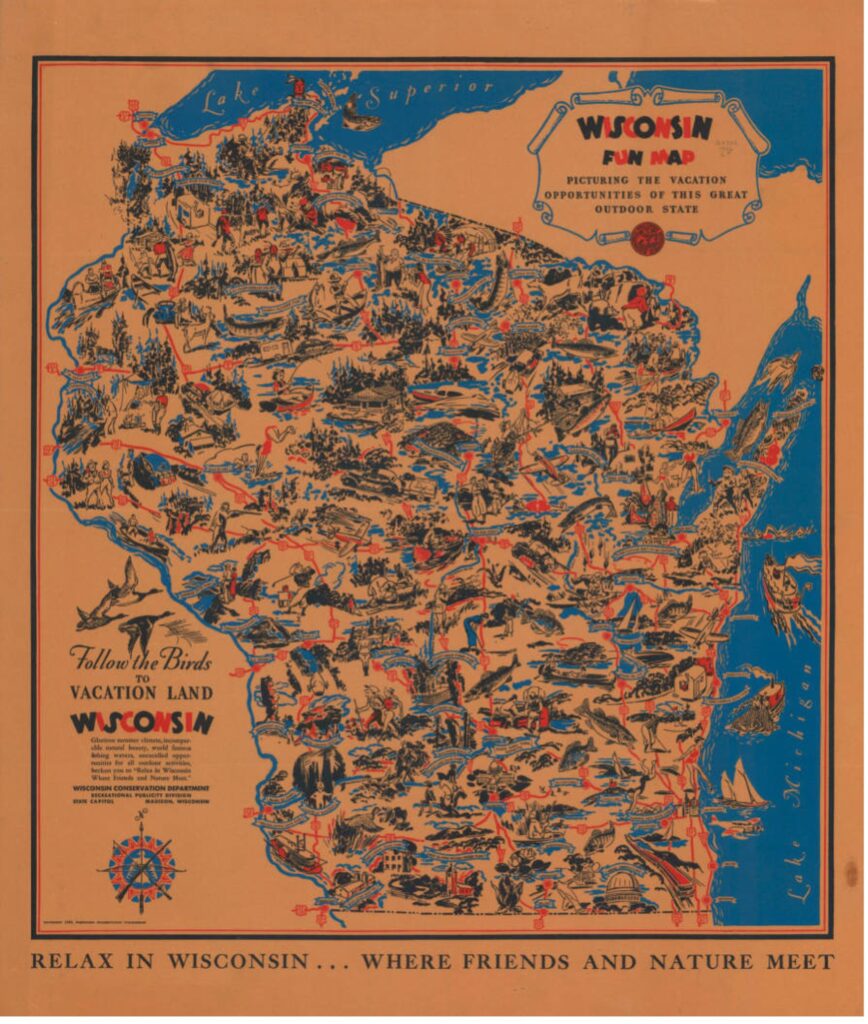

While nature in Wisconsin draws visitors to enjoy the lakes and land of the state, other non-natural elements, like private advertisement and state promotion, have also helped to stimulate tourism over the years. Wisconsin didn’t become “Vacation-Land” overnight, and through marketing and publicity, both private businesses and public organizations worked to promote recreation as a pillar of the state identity.

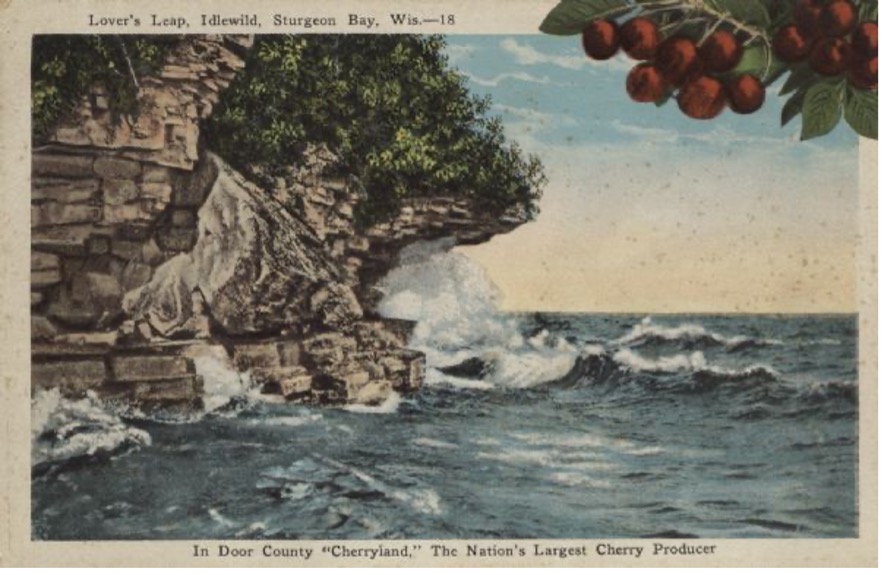

As Wisconsin’s businesses began to capitalize on the state’s natural beauty and resources in the late 19th century, a variety of sites and activities began to draw attention. From medicinal mineral springs in Waukesha, to rustic winter sports in Wausau, to nature and agriculture in Door County, to fishing in the Northwoods, tourism flourished on the appeal of Wisconsin nature. Tourism industries grew through advertisement, as private enterprises promoted their businesses. Photography, advertisements, and postcards helped to spread the word. As these businesses promoted their products and services, they helped to redefine local identities and economies. Waukesha went from a prairie town to a hub of health tourism, Wausau transformed from a logging resource to an outdoor retreat, Door County became “Cherryland,” and the Northwoods developed into a fishing destination.

Public agencies also stepped in to promote tourism by different means. In the early 20th century, the first State Park Board of Wisconsin formed to consider creating the state park system. They proposed four sites – Devil’s Lake, the Door County Peninsula, the Mississippi Bluffs, and the Wisconsin Dells – and recommended investment in state highways to connect the system. In contrast to private developments, as seen in Waukesha County and Lake Geneva, Nolen and the State Park Board advocated for the preservation of public lands. Not only would the state park system provide access to recreation and enjoyment of Wisconsin’s natural spaces, but also conserve environmental resources, invigorate local economies, and draw new residents to the state.

Both the natural landscape and manufactured promotion helped to attract visitors to Wisconsin. Throughout the seasons, tourists enjoyed different recreational pastimes across the state and over the years.

Summer Recreation in Wisconsin `

Throughout Wisconsin history, the pleasant summer months have provided plentiful opportunities for recreation and tourism. People in the past enjoyed many of the same summertime activities as we do today, like swimming and playing sports. Wisconsin 101 contains a number of object histories and stories that help us to appreciate those attractions.

In Waukesha, mineral spring water grew popular for its healing properties in the late 19th century. For decades, the county was home to a bustling resort culture in the summer months. Midwestern urbanites flocked to the prairie town for the medicinal spring water and stayed for the fun at the county’s many hotels and parks. The Henk Mineral Spring Water Bottle showcases the businesses that flourished due to the popularity of Waukesha water.

Meanwhile, the natural beauty of Door County drew visitors to enjoy the summer on the peninsula. Later, the cherry industry attracted tourists to the blossoming orchards and enjoy festivals and golf tournaments. The Cherryland T-Shirt is just one product created to promote tourism in the region.

Further “up nort’,” the lakes and forests of the Northwoods became a hub for vacationing and outdoors activities. Swimming, boating, and fishing at lakeside resorts became major tourist attractions. The Mepps Fishing Lure demonstrates how equipment helped to promote fishing as a recreational activity in the area.

Although summertime has brought many folks to Wisconsin over the years, the snowy winter months have also drawn visitors to enjoy sports and recreation.

Winter Recreation in Wisconsin

In more recent history, the winter months have also become a popular time to enjoy the great outdoors. Wausau, for example, hosted a popular winter sports festival throughout the 1920’s. The festival presented tournaments for skiing, sledding, skating, and more, and drew visitors and competitors from Milwaukee and Minnesota. Aside from celebrating winter fun, the festival also helped to revitalize the local Wausau economy as the logging industry declined. The Hudson’s Bay Company Point Blanket Coat helps us to understand how people bundled up against the chilly weather at tournaments like this.

Other events and activities have brought people to wintery Wisconsin. For example, Tony Wise started the American Birkebeiner race in 1973. Named after a famous Norwegian historical event, the Nordic ski race runs from Cable to Hayward, Wisconsin. The race remains the largest cross-country skiing race in North America, attracting skiers and visitors from across the United States and around the world.

Transportation and Travel

Railways were an important mode of transportation throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Connecting major cities throughout Wisconsin and the Midwest, trains carried passengers to destinations throughout the state. The first train in Wisconsin ran from Milwaukee to Waukesha in 1851. Later, railroads were developed to connect Lake Michigan with the Mississippi river, running through Milwaukee, Madison, and Prairie Du Chien. Another railroad that connected Wisconsin from east to west ran from Milwaukee to La Crosse. Trains also ran north from Chicago, opening the state to tourists from the largest city in the Midwest. Meanwhile, passenger steamships ferried travelers to stops along the coast of Lake Michigan.

Sometimes, the journey can be just as much a part of the fun as the destination. In the 19th century, bicyclists certainly thought so as they explored Wisconsin’s outdoors on two wheels. Travelers took to the countryside for camping and sightseeing, and visited major attractions across the state, such as Lake Superior’s ice caves, Devil’s Lake, and Yerkes Telescope.

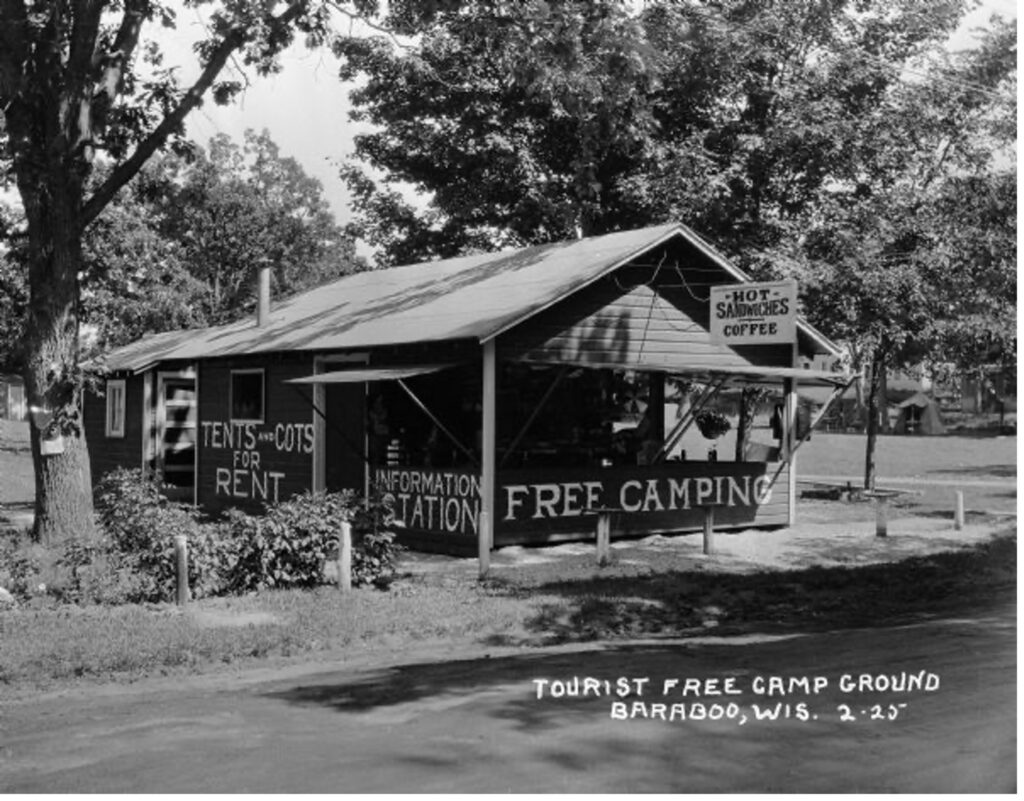

The advent of the automobile stimulated demand for roads that were better suited to motorized travel. By the 1910’s, Wisconsin began investing in developments of trails into roads, which continued through the mid-20th century to create the state highway system. The automobile also changed the way that people travelled. Tourists travelling by car had more freedom in choosing their destinations and could move more quickly across the state. Instead of relying on hotels, resorts, and railway schedules, people chose to set up camp along the way. Eventually, communities developed free, and later ticketed, campgrounds.

Created by Sara Mulrooney, May 2023

SOURCES

Nolen, John. State Parks for Wisconsin. Madison: State Park Board, 1909.

Shapiro, Aaron. “Up North on Vacation: Tourism and Resorts in Wisconsin’s North Woods 1900-1945.” The Wisconsin Magazine of History 89, no. 4 (Summer 2006): 2-13

Wisconsin Historical Society. “The Physical Geography of Wisconsin.” Turning Points in Wisconsin History, Wisconsin Historical Society, Accessed 2023. https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/turningpoints/tp-001/?action=more_essay

Wisconsin Historical Society. “Travel and Tourism.” Turning Points in Wisconsin History, Wisconsin Historical Society, Accessed 2023. https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/turningpoints/tp-034/?action=more_essay