Wisconsin passed the nation’s first constitutionally upheld worker’s compensation law in 1911. It is one of the great successes of Progressive-era social legislation and a triumph of the Wisconsin Idea.1

Previously, American workers toiling in industrialized workplaces had often faced the threat of injury at work. Factories could be dark and unsanitary, with loud machines that could easily maim or kill if they caught a stray finger or scrap of loose clothing. There was little incentive for employers to improve the safety of their factories since an abundance of willing workers could replace hurt or killed employees and the government issued few, if any, penalties.

Before the 1911 Law, the only way an employee injured at work could receive any compensation was to sue his or her employer for negligence; an expensive and lengthy process. Indeed, employers often avoided blame for accidents that injured, maimed, or killed employees by using legal loopholes. For example, employers would blame other employees for the incident, or would avoid the question altogether by asserting that the injured worker had knowingly accepted a dangerous job, thereby waiving his or her rights to a safe workplace.

Besides being unfair, this system was very costly. A 1908 study estimated that for every $18 in compensation won by workers, $82 were spent in legal costs. And even though the burden of proof lay with workers—thus discouraging many from seeking compensation—the number of cases in Wisconsin alone was steadily rising.2

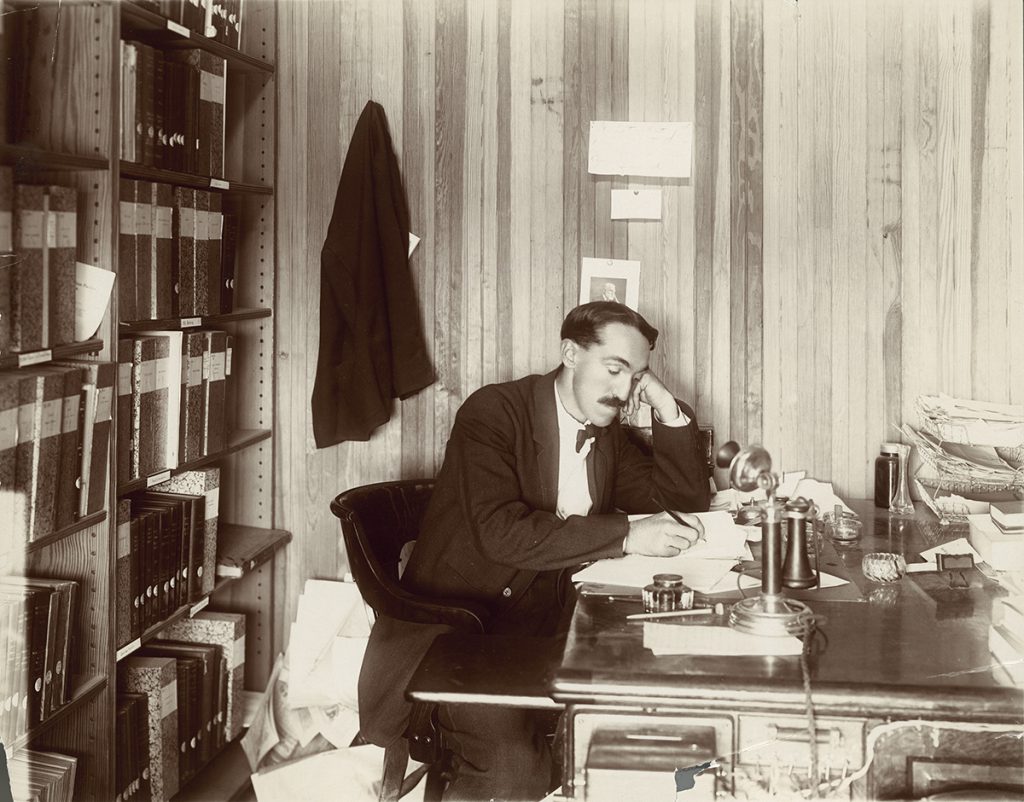

In 1909, the Wisconsin State Legislature created the Industrial Insurance Committee to address the problem. Headed by Senators Albert Sanborn from Ashland and John Blaine of Boscobel, the committee proposed a workers compensation insurance law in January 1911. Scholars like economist John R. Commons of the University of Wisconsin and the political scientist Charles McCarthy of the Legislative Reference Library had greatly influenced the legislation. After some debate, a coalition of progressive Republicans and Social Democrats passed the bill, and on May 4, 1911, it was signed into law by Governor Francis McGovern.

Birth of an Industry

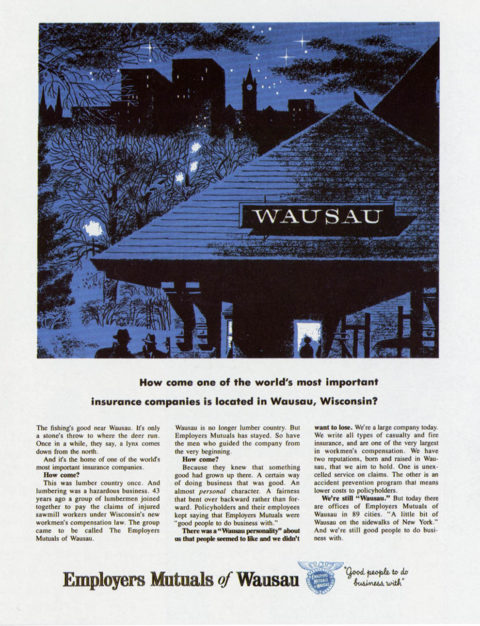

In response to the Workmen’s Compensation Act and the many similar state laws that followed, a whole new insurance industry was born, with the first company emerging in Wausau, Wisconsin. Soon after passage of the 1911 law, a circle of influential businessmen called The Wausau Group founded the Employers Mutual Liability Insurance Company of Wisconsin. This new company would provide workers compensation insurance for the many businesses controlled by the Wausau Group.

On September 1st, 1911, Employers Mutual issued the first policy under Wisconsin’s new workers compensation law to Wausau Sulfite Fibre Company (later renamed Mosinee Paper).

As Employers Mutual grew over the years, it expanded into other kinds of insurance—including fire, life, and liability policies—but worker’s compensation remained a central part of their business. Over the course of the 20th century, Employers Mutual would open branch offices across the United States and ensure millions of workers. Employers Mutual’s success was due in large part to the company’s efforts to promote safety education and injury prevention through innovations like workplace hearing tests and its prolific publishing departments both at the Wausau headquarters and its many branches across North America.

Despite its growth to become one of the top insurance companies in the country, Employers Mutual remained a small town Wisconsin company headquartered in Wausau, WI. In 1979, the company decided to change its name. After 68 years, the Employers Mutual Liability Insurance Company of Wisconsin became Wausau Insurance, in part to promote a better brand for the company. Since the 1950s, ad campaigns had stressed that the company was made up of “good people to do business with” because of its “Wausau personality.”

The 1911 Workmen’s Compensation Law provided a legal path to establishing a new worker’s compensation insurance system. But by taking out insurance policies to guard against dangers to their employees, employers also had to acknowledge that they could be held accountable for injury or death of people on their payroll. And so the Wisconsin law also created a legal precedent for the right to a safe workplace for all employees.

Written by Ben Clark, November 2016.

FOOTNOTES

- Stark, Jack. “The Wisconsin Idea: The University’s Service to the State” from The State of Wisconsin 1995-1996 Blue Book (Madison: Wisconsin Legislative Reference Bureau, 1995), 99-171.

- Buenker, John D. The History of Wisconsin: Volume IV, the Progressive Era, 1893-1914 (Madison; State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1998), 266, 544-548.

- Borgnis and others v. The Falk Company. 147 Wis. 327 (S.C. WI 1911).