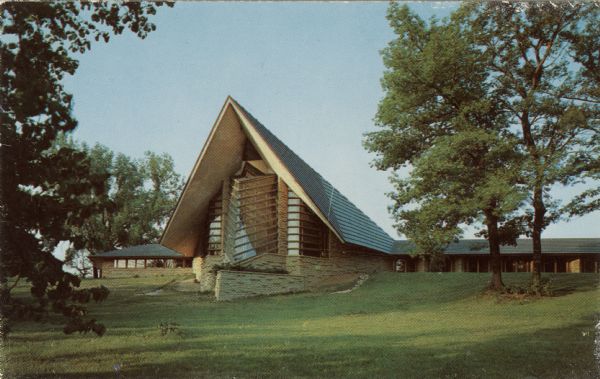

Once enjoying unobstructed views of Lake Mendota and sharing its land with the University of Wisconsin’s experimental fields, the First Unitarian Society Meeting House now sits on UW-Madison’s Medical campus. Designed in 1947 by Frank Lloyd Wright to embody the mission of the First Unitarian Society and egalitarian vision of its minister, Rev. Kenneth Patton, the Meeting House served as a space that encouraged diverse groups to connect. Registered as a National Historic Landmark, the Meeting House is one of seventeen buildings recognized by the American Institute of Architects as staples of Frank Lloyd Wright’s work.[1]

From 1942 to 1949, Patton, a known universalist, led the ministry of the First Unitarian Society. His ministry predated and contributed to the merging of Unitarianism and Universalism in the United States. Originating in Europe at the time of the Protestant Reformation, Unitarianism evolved independently in America, yet maintained a rejection of the Holy Trinity— its name, “Unitarian”, derived from the belief that God is one.[2] Universalists believed in universal salvation, that no person should be condemned by God to eternal damnation. In 1961, these religious movements merged to form the Unitarian Universalist Association (UUA).[3] Today. the First Unitarian Society of Madison is one of 1,000 congregations affiliated with the UUA.

When faced with designing and building a meeting house for the First Unitarian Society in 1946, Patton sparked controversy in commissioning Frank Lloyd Wright. Although Wright had long, personal ties to the society—his father helped found the church and his mother taught Sunday school and led the women’s group—his reputation as “arrogant” and “recklessly extravagant” preceded him.[4] Nevertheless, after a close vote by the congregation, Wright got the job.

Completed in 1951, the meeting house reflected both Unitarian principles—freedom, reason, and tolerance— and Patton’s Universalist outlook. Wright united the three typically separate parts of a traditional church—the steeple, the auditorium, and the secular area—into one organic and free-flowing space. The high ceilings and extensive windows throughout the hallways and larger spaces provide an open feeling that echoes the beliefs of the Society.[5] More broadly, the meeting house exemplified broader national trends that saw a shift from urban to suburban churches and a rise in religious sentiment that pervaded the country after the war.

A bench from the Meeting House of Madison, also designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, encapsulates the essence of the Society. Modest, yet functional, this piece reflects the flexibility of Unitarianism. For decades, the bench and other furnishings designed by Wright were used to support lectures, dinner events, and weddings. Members could readily arrange the lightweight benches to facilitate inclusion and discussion. Thus, not only the space of the Meeting House but even the objects within it served to bring together Madison’s community of Unitarians.

Written by Anna Michalski, August 2021.

FOOTNOTES

[1]“The First Unitarian Society’s Meeting House,” Friends of the Meeting House, accessed August 18, 2021, https://www.unitarianmeetinghouse.org/.

[2] Andrea Greenwood and Mark W. Harris, An Introduction to the Unitarian and Universalist Traditions (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011).

[3] Cordes, Ron, and Naomi King, “History of Unitarian Universalism,” UAA.org, Unitarian Universalist Association, October 29, 2020, https://www.uua.org/beliefs/who-we-are/history.

[4] United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, National Historic Landmark Nomination Form: First Unitarian Society Meeting House, by Anne E. Biebel, Mary Jane Hamilton, Abigail Markwyn, Jonathan Kasparek, and Melinda Osman, Madison, WI, 2002, https://npgallery.nps.gov/GetAsset/b8f04c33-131c-4b19-9b8a-c5f4ac884f83

[5] Dougles M. Steiner, “Unitarian Meeting House Interior,” The Wright Library, accessed August 18, 2021, http://www.steinerag.com/flw/Artifact%20Pages/UnitarianMH.htm.