Prior to the Civil War, most of northern Wisconsin was inhabited by the Menominee and Ojibwe Indians and transient fur traders of European origin. Demand for wood in Chicago and Milwaukee after the Civil War brought lumbermen to the north woods. Initially, most harvesting focused on the “pineries,” since softwoods like pine could be floated down rivers, the major means of transportation at the time. In northeastern Wisconsin, three major river networks sent logs to either Green Bay (and then on to Milwaukee and Chicago), Oshkosh, or various mills along the Wisconsin River from Rhinelander to Wisconsin Rapids. It wasn’t until the early 1880s that the expansion of railroads in northern Wisconsin opened new areas for the lumber industry, especially for hardwoods like maple, which could not be floated down rivers. Railroads continued to be the primary method of transporting logs until the 1930s, when improved roads allowed trucking to surpass rail.

Although the early days of river log drives in the pineries brought lumbermen to remote areas of northern Wisconsin, the industry didn’t result in much permanent settlement since these loggers were often nomadic and camps short-lived. It was the railroads that led to the creation of numerous sawmills and the towns that supported them in the north woods. Most cities north of a line from Fond du Lac to La Crosse began as lumber towns connected to markets by the railway. Some thrived, and some would become ghost towns when the forests were depleted.

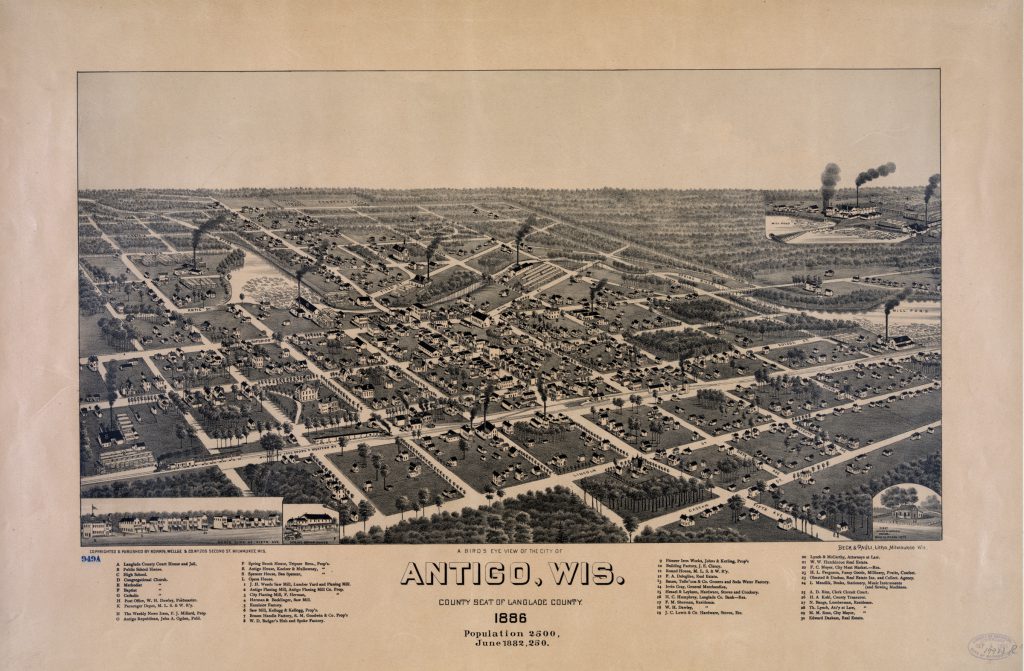

Antigo: A Lumber Town

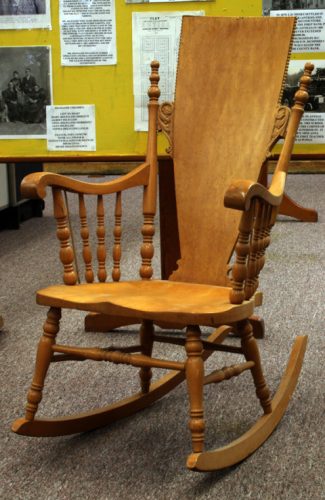

The city of Antigo was founded by Francis Deleglise who came from Appleton as a timber cruiser in the late 1870s. With no major navigable rivers in the region, it wasn’t until the coming of the railroad in 1882 that the timber industry developed. This city map of 1886 shows five manufacturers of wood products lining a downtown lake that had been created by damming a small river. One major manufacturer, the Crocker Chair Company, built its own rail line to bring timber into town from “the Crocker Hills,” about 15 miles away. Other mills were scattered throughout Langlade County with major operations in White Lake and Elcho. A few decades later in 1925, the Vulcan Corporation established a factory for making wooden shoe lasts and bowling pins in Antigo precisely because of the town’s lumber-oriented rail service.

The Northwoods lumber industry also had an associated lore of songs and stories, particularly in the days of the river drives. Lumberjacks from various ethnic backgrounds would sing songs about their lives while often playing on crude homemade instruments. Some of these were collected and recorded as part of the Federal Writers Project—part of the Works Projects Administration of the New Deal—and by folklorist Alan Lomax.

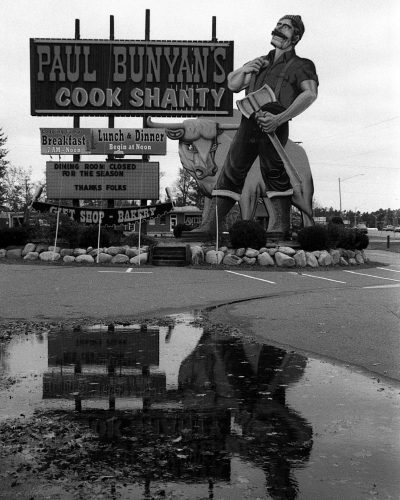

Perhaps one of the most well-known characters in logging lore was the mythological figure Paul Bunyan, whose exploits were celebrated in stories told throughout Wisconsin, Minnesota, and central Canada.

Bernice Stewart, a former English major at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and one-time Antigo resident, was one of the first people to study the origins of this oral tradition. Stewart grew up in small logging towns across northern Wisconsin and Upper Michigan. Her father was a timber cruiser who travelled and visited lumber camps, often taking Bernice with him. After writing about her childhood experiences in college, Stewart then collaborated with UW-Madison English professor Homer Watt to produce one of the first scholarly reports on Paul Bunyan’s mythology in 1916.

Today, the timber industry is still a major part of the economy of Langlade County and Wisconsin. Department of Natural Resources statistics show that lumber generates 422 jobs in Langlade County with 495 indirect jobs and an economic impact of close to $65 million annually. State-wide, forest products create almost 60,000 jobs with an economic impact of close to $23 billion.

Written by Joe Hermolin, February 2016.

SOURCES

Mary Roddis Connor, “Logging in Northeastern Wisconsin,” Proceedings of the Third Annual Meeting of Forest History Association of Wisconsin, Inc. (Wausau, WI: Forest History Association of Wisconsin, 1978), 31-38.

Robert E. Dessureau, History of Langlade County (Antigo, WI: Berner Brothers Publishing, 1922), 50.

Michael Edmonds, Out of the Northwoods: The Many Lives of Paul Bunyan, With More than 100 Logging Camp Tales. Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2009.

James P. Kaysen, “Railroad Logging in Wisconsin,” Proceedings of the Third Annual Meeting of Forest History Association of Wisconsin, Inc. (Wausau, WI: Forest History Association of Wisconsin, 1978), 39-44.

James P. Leary, Folksongs of Another America: Field Recordings from the Upper Midwest 1937-1946. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2015.

Harry B. Peters, ed., Folk Songs out of Wisconsin: An Illustrated Compendium of Words and Music. Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1977; 7.

Randall E. Rohe, Vanished Lumber Towns of Wisconsin (Marinette, WI: Forest History Association of Wisconsin, 2002), 1-4.

Michael F. Sohasky, “The Upper Wolf River: The Vast Pinery,” Proceedings of the Thirteenth Annual Meeting of Forest History Association of Wisconsin, Inc. (Wausau, WI: Forest History Association of Wisconsin, 1988), 14-19.

Larry van Goethem, Not Long Ago. (Antigo, WI: Langlade County Historical Society, 1979), 133-141.

Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, “Forestry and the Wisconsin Economy,” Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, accessed January 2016, http://dnr.wi.gov/topic/forestbusinesses/factsheets.html

This Post Has 2 Comments

Comments are closed.

And yet another Wisconsin history of logging site that ignores the contributions of NW Wisconsin. Hayward, Drummond, Cable, Spooner, Ashland, Bayfield, Superior, Brule, Danbury, Rice Lake have apparently disappeared from the landscape. Where did all those pineries go? Where did the first millionaire in the Weyerhaeuser Logging Company build his mansion? What about the CCC’s and reforestation projects?

You’re absolutely right! There’s much more history to tell, and we’re always looking for contributers. Click on the “Write for Wisconsin 101” link at the top of the page to help us tell more of our state’s story.