In 1929, the United States fell into the deepest economic hole the country has known: the Great Depression. Over the three years following the economy’s collapse in 1929, 3,392 banks across the country closed their doors and over $1 billion in deposits vanished. Before the collapse, the Bureau of Labor Statistics estimated 3.1% of America’s labor force was unemployed; by 1933, that number had surpassed 25%. Wisconsin was not spared. In 1929, Wisconsin had 964 banks with deposits totalling more than $964 million. By 1933, those numbers had plummeted to 401 banks and deposits of over just $450 million; over half of Wisconsin’s savings had disappeared in only four years.

To combat the ongoing depression, Wisconsin legislators approved the newly formed federal agency, the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), to come to Wisconsin in 1933. The CCC was one of the many “alphabet agencies” formed by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s administration and provided jobs to millions of Americans during the Great Depression. From planting trees to clearing fire lanes, the CCC served as temporary employment to thousands of Wisconsinites who had few other job prospects. By 1935, however, some Wisconsinites felt the agency was doing little to help those struggling through the depression, questioning the necessity of conservation efforts when many across the state were starving. In response, the state government brought an additional federal work relief agency to Wisconsin in 1935: the Works Progress Administration, or WPA.

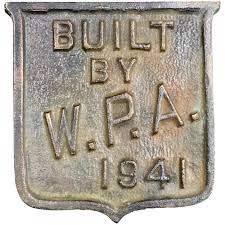

Wisconsin participated eagerly in the federal WPA program, quickly setting up a state administration and giving work to thousands of Wisconsinites after its inception. Rather than completing conservation-based projects like the CCC, the WPA organized construction crews with the intent to strengthen Wisconsin’s infrastructure. In order to ensure the WPA was benefiting the public, one main requirement of a potential project was that “The project must have been of general public usefulness”(Lackore 1966, 14). In total, WPA crews constructed over 22,800 miles of road, laid 1,588 miles of water pipes and sewers, put up nearly 1,500 new buildings, constructed over 500 dams, built 17 airports, and even planted 63 million trees across the state, contributing to the CCC’s efforts as well. They also helped construct many of Wisconsin’s state parks and their respective facilities, including the Lapham Peak Observation Tower at Lapham Peak state park in Delafield. It is safe to say that you probably use something built by the WPA every day!

While the WPA proved integral to Wisconsin’s recovery from the Great Depression, it soon became unnecessary to the state. The WPA was officially discontinued in 1943 as the economic boom from World War II eliminated the issue of unemployment. Other federal work relief agencies such as the CCC were also phased out at that time. In its eight years of service, the WPA had employed an average of 43,000 workers per year and had given jobs to hundreds of thousands of Wisconsinites in total. In its short existence, the WPA paid Wisconsin workers over $220 million in wages, helping to kickstart the economy and bring Wisconsin back from the depths of the depression.

Written by Cole Roecker

SOURCES

Lackore, James. 1966. “The WPA in Wisconsin.” M.A Thesis, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Wisconsin Historical Society. “WPA (in Wisconsin).” Accessed August 5, 2020. https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS462

Carol Ahlgren. 1988. “The Civilian Conservation Corps and Wisconsin State Park Development.” Wisconsin Magazine of History 71, 3: 184-204.

Wisconsin Historical Society. “Lapham, Increase, 1811-1875; Wisconsin’s First Scientist.” Accessed on August 3, 2020. https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS527#:~:text=Increase%20Lapham%20Examining%20a%20Meteorite%2C%201871%20ca.&text=A%20self%2Deducated%20engineer%20and,one%20of%20its%20foremost%20citizens.&text=Increase%20Allen%20Lapham%20was%20born,%2C%20on%20March%207%2C%201811.

Barquist, Barbara; Barquist, David. 1987. “The Beginning.” Haley, Leroy (ed.). The Summit of Oconomowoc: 150 Years of Summit Town. Summit History Group: 9.