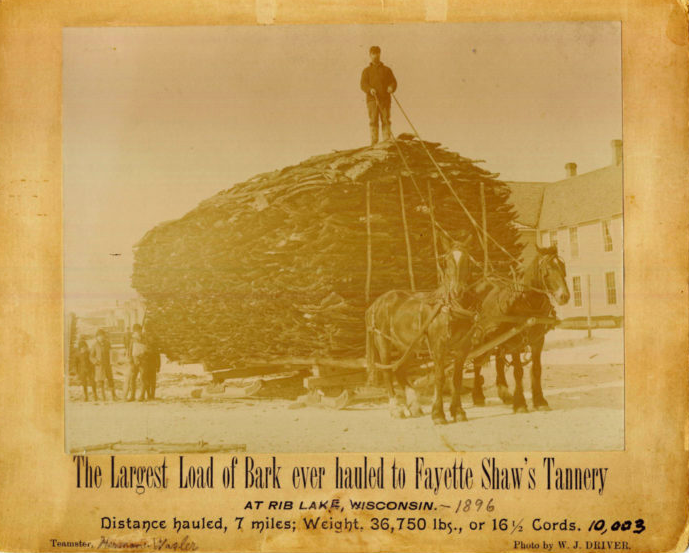

The bark spud is an iron tool used to remove bark from cut timber. Most bark spuds have a steel head with a hard wooden handle. The head is rounded or dish-shaped and has one cutting edge. The sharp wedge on the end of the bark spud slides between bark and wood on a log and helps to peel the bark off in long strips. In Wisconsin, men peeled bark from hemlock trees in spring and summer. In winter, they piled the bark onto sleds and took it to the tanneries. The sleds could weigh as much as 23 tons! This bark spud is from the Kuse Farm Museum and Nature Preserve in Medford, WI in Taylor County.

The bark spud is an iron tool used to remove bark from cut timber. Most bark spuds have a steel head with a hard wooden handle. The head is rounded or dish-shaped and has one cutting edge. The sharp wedge on the end of the bark spud slides between bark and wood on a log and helps to peel the bark off in long strips. In Wisconsin, men peeled bark from hemlock trees in spring and summer. In winter, they piled the bark onto sleds and took it to the tanneries. The sleds could weigh as much as 23 tons! This bark spud is from the Kuse Farm Museum and Nature Preserve in Medford, WI in Taylor County.

Peeling Bark for Cash in Taylor County

The Kuse family moved to Medford in 1883 at the start of the tanning boom in the area. Although they farmed during the summer, in Taylor County peeling bark was a common way to earn extra money during the spring. It is easiest to peel bark during spring and summer months when the sap is running. Peeling bark was a way for families to earn extra income during slow periods, and the Kuse family likely used the bark spud for this purpose.

When the Kuse family moved to Medford, the bark spud was likely used for peeling bark from hemlock trees for the local tanning industry. The tanning industry thrived in the cutover areas of northern Wisconsin. After logging companies had cut the most valuable stands of white pine, they left less valuable stands of hardwoods like oaks and hemlocks, which were then peeled of their bark.

The tanning boom in Taylor County declined by the 1920s, and with it the demand for hemlock bark. In the next decades, the first generation of softwoods that grew in the cutover areas matured, and by the 1960s they had grown large enough to harvest. In the 1960s and 1970s, people in Taylor County took up their bark spuds once again. This time they peeled the bark from softwoods like aspen and birch. Peeling aspen bark was known as “peeling popple” and instead of selling the bark this time, Taylor County residents sold the peeled wood to the paper companies. Paper companies used peeled spring aspen to make high quality paper tissues.

Tanning Hides with Bark

Although a bark spud was a useful and commonplace object in any Wisconsin logging camp, it has a special relationship with the hemlock lumbering and leather tanning industries that developed in Taylor County. After most of the pines in northern Wisconsin were felled, logging companies looked for new ways to continue their work, hoping to make money on the remaining stands of oak and hemlock. Some companies turned to making oak furniture, others began to mine iron ore, and still others began to harvest hemlock bark for tanning.

Oak, hemlock, and chestnut trees all produce tannin, a bitter chemical that protects the trees against insects. For millennia, people have extracted the tannin from trees and used it to preserve animal hides to make leather. Tanners used the chemicals in hemlock bark to alter the protein structure of cow hides to make the hides more durable, flexible, and long-lasting. The process is called tanning.

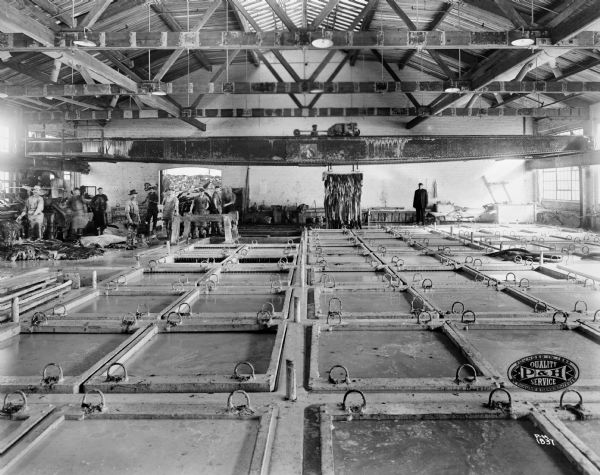

To tan leather, tanners soak the hide to loosen the hair, scrape it to remove hair, and then soak the hide in a vat filled with water and bark. After soaking in the vat for a day or so, the hides are hung up to dry. This process could be very smelly, and the run-off water from the tanning vats was unsafe to drink.

The tanners in Taylor County use cow hides to make high quality leather for boots and horse tackle. Other tanneries specialized in tanning other kinds of animal hides. In the video below, the workers are tanning sheep hides to make expensive women’s gloves.

Tanning in Taylor County

In early 1890, members of a wealthy Boston-based family, the Shaws, visited Wisconsin to find new sources for the tannic acid needed to produced leather for horse harnesses and boots. The Shaw Family operated tanneries in Maine, Massachusetts, and Canada, and were looking for a new place to do business. They chose Taylor County for their new operation because the county had many forests, was close to several tanneries, and had access to both the Soo Line and Chicago-based railroads.

The cut-over areas of northern Wisconsin were ideal settings for tanneries. The region was already set-up for large scale logging operations, so transitioning from felling white pine to felling hemlocks was relatively simple. With the decimation of the white pine forests, there were also many former loggers in the region looking for employment, and a large labor pool made it easier for tanners, like the Shaws, to recruit people to work in their very smelly industry. Additionally, tanneries needed easy access to large amounts of water, so areas with many streams like Taylor County were appealing settings for tanneries.

Soon, tanneries across Taylor County began to receive cow hides sent by the Shaw Family from locations as far away as South America. Though there were cows in Taylor County, the Shaw family primarily chose to ship hides from cattle herds in Central and South America as well as the American Southwest. It was cheaper to send the hides to Taylor County then to send the bark to where the hides were produced.

To meet the volume of hides, the Shaws contracted with local tanneries and built their own. Although they existed before the tanning industry, the communities of Medford, Rib Lake, and Perkinstown grew around the Shaw company tanneries. Workers at the Shaw family tanneries earned about $8 per week. By April 1890, the tannery in Medford produced more than two tons of tanned leather each day.

Tanning in Wisconsin

The conditions that made Taylor County the Shaw’s choice for leather production drew other tanners to the state as well. By 1900, Wisconsin produced nearly 15% of the nation’s tanned leather, with the majority of the tanneries centered in Milwaukee. Unlike the Shaw’s operation in Taylor County that worked with hides shipped from afar, in Milwaukee the tanning industry grew alongside the stockyards. Farmers and ranchers across the upper Midwest and American southwest, sent their cattle to Milwaukee and Chicago to be butchered and have their hides turned into leather. Tanners in Milwaukee imported bark from the cutover district, transporting it by rail to the tanneries outside the city.

By 1910, Milwaukee was the world’s largest center for leather production, but the industry rapidly declined over the next few decades as alternatives to tanning with bark became available. The tanneries in Taylor County also declined during that period, with the major operation in Medford shutting its doors in 1919.

When the tanning industry left Taylor County, the region turned to the paper industry and tourism. In this new era, the bark spud remained in use—now for peeling bark from poplar and aspen logs on their way to the paper mill or for peeling bark from trees to make rustic-style furniture and cabins.

From peeling hemlock bark for the tanning industry to peeling popple for the paper industry, the history of Taylor County residents peeling bark with bark spuds illustrates the creative ways communities adapt to a changing environment and economy.

HOW TO: Peel Bark

HOW TO: Tan Bark

Written by Hildegard Kuse and Loretta Kuse, April 2019.