The Wisconsin Chair Company’s (WCC) decision to enter the record label industry was an economic one. With their subsidiary company, the United Phonographic Corporation (UPC), picking up steam, management at the WCC began pressing records. The UPC’s first record labels, Puritan and Vista, failed commercially. In late 1917 the UPC incorporated Paramount Records and began pressing records at a New York factory (owned by another WCC subsidiary, the New York Recording Laboratories). In its early years, Paramount recorded a wide variety of records, including music popular within ethnic immigrant communities (especially from southern and eastern Europe), orchestral pieces, and comedic presentations by vaudeville performers. These productions, however, were not very successful, as Paramount barely broke even its first years of production.

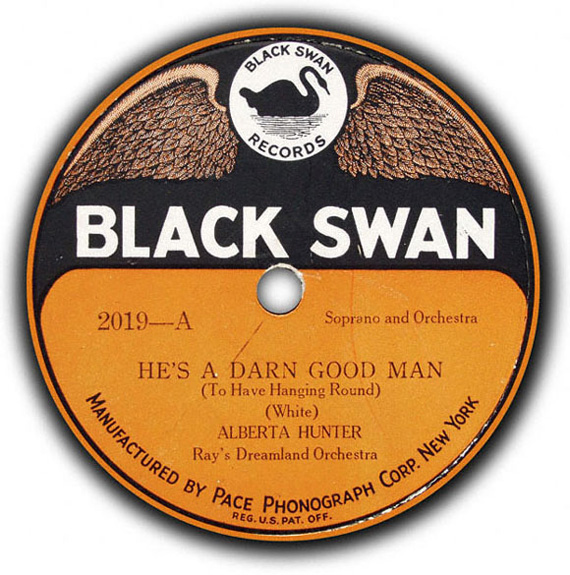

By the early 1920s, Paramount had yet to find a musical niche market to help it turn a respectable profit. Economic and demographic changes after World War I, however, had opened a whole new customer base for the record production industry: African Americans. Like other record companies in the post-war years, Paramount entered the new field of “race music” in 1922 and began producing music by black artists for black customers. Just one year later, the Wisconsin company had solidified its status as one of the leading “race label” companies in the United States. Two factors propelled Paramount to the head of the field. First, Paramount management hired a young black journalist stationed in Chicago named J. Mayo Williams, who, despite having nearly no experience in the record industry, proved very effective in recruiting black artists to the Paramount label. Second, Paramount, which made much of their profit in the early 1920s by pressing discs for other record companies, purchased one of their “race music” clients, Black Swan Records in 1924, opening a larger customer base that expanded into the American South. Thanks to the recruitment efforts of Williams, Paramount became the premier record label producing music for black audiences, specializing in the blues craze of the mid 1920s.

In 1929, hoping to cut down costs associated with renting out recording studios in New York and Chicago, the UPC, Paramount’s parent organization, built their own recording studio in Grafton, Wisconsin. Paramount’s quick economic ascent proved to be short lived, however. The economic turmoil caused by the Great Depression resulted in less disposal income for Americans to spend on recreational purchases like records and phonograph cabinets, decimating the American recording industry. Paramount was one of the first record companies to fold in the United States, closing the doors of its Grafton studio in 1935.

Written by Sergio M. Gonzalez, February 2014.

SOURCES

Sarah Filzen, “The Rise and Fall of Paramount Records.” The Wisconsin Magazine of History 82:2 (Winter, 1998-1999): 104-127.

Edward Komara, “Blues in the Round.” Black Music Research Journal 17:1 (Spring, 1997): 3-36.

Edward McClelland, “The Complicated Record Exec Left Out of Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom,” Chicago Magazine, 20 January 2021. https://www.chicagomag.com/arts-culture/ma-rainey-j-mayo-williams/

Robert Springer, “Commercialism and Exploitation.” Popular Music 26:1 (Jan. 2007): 33-45.

Alex Van der Tuuk, Paramount’s Rise and Fall. Denver: Mainspring Press, 2003.

RELATED STORIES

OBJECT HISTORY: Paramount Records 78

The Wisconsin Chair Company

The Record Production Process

Recruiting Talent