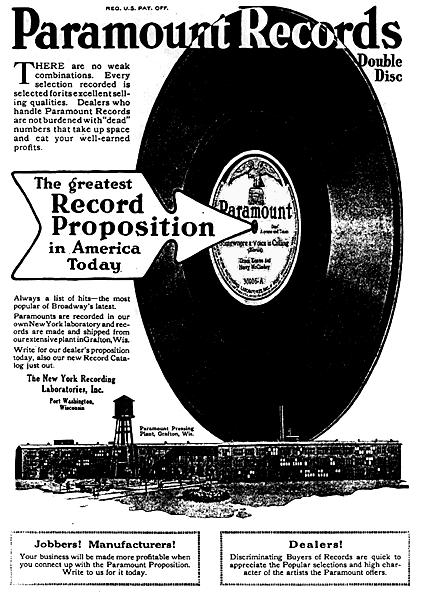

Paramount Record’s parent company, the United Phonographic Corporation, a subsidiary of the Wisconsin Chair Company, decided to begin recording and pressing records to include with their phonograph cabinets in the early 1920s. Paramount initially recorded in studios throughout the United States. They first rented recording studios in New York, but then moved most of their sessions to Chicago, which was more centrally located for artists traveling from the southern states. To save money, Paramount eventually created their own recording studio inside the same Grafton plant pressing their records. Acoustics were so poor, however, that sound engineers were forced to used burlap sacks to cover the walls of the studio. The Grafton studio was remote and isolated. Because the Hotel Grafton didn’t allow black customers, black recording artists were forced to spend their nights in nearby Milwaukee, and then take the train into Grafton to record during the day.

A standard recording session lasted for three hours, allowing artists to record three to four songs. The first test recording was cut on wax masters to determine the sound quality. Once the wax master was produced, it was packed in dry ice and sent to the pressing plant in Grafton, Wisconsin, eight miles southwest of the parent corporation Wisconsin Chair Company in Port Washington. There, workers brushed the wax master with graphite and copper-platted it, producing the metal master, which would be used for the record production process. Workers at the Grafton plant then created shells made of the metal masters, which they then placed in a record press with a mixture of local clay, shellac, and ground stone.

The Grafton plant was truly a low-cost production. Most of the employees were poorly trained and were instructed to focus on efficiency in order to create a cheap product. Records produced by Paramount were known for their poor sound quality. With the emergence of electric recording techniques in the late 1920s, Paramount began to face stiff competition from other recording studios. These new procedures better captured singers’ voices and produced a much clearer and better-quality recording. Paramount, more interested in their bottom line, refused to invest in electric recording.

To learn more about the record production process: How to Make a Paramount Record (1930) from kellianderson on Vimeo.

Written by Sergio M. González.

SOURCES

Filzen, Sarah. “The Rise and Fall of Paramount Records.” The Wisconsin Magazine of History 82:2 (Winter, 1998-1999): 104-127.

Komara, Edward. “Blues in the Round.” Black Music Research Journal 17:1 (Spring, 1997): 3-36.

Springer, Robert. “Commercialism and Exploitation.” Popular Music 26:1 (Jan. 2007): 33-45.

Van der Tuuk, Alex. Paramount’s Rise and Fall. Denver: Mainspring Press, 2003.

Featured image: Disc cutting lathe from the 1930s. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.