With a roster that included Louis Armstrong, Jelly Roll Morton, and Ethel Waters, Paramount Records became perhaps the most important blues recording company of the 1920s. Their success was dependent on their ability to recruit black performers and reach a broad black audience. With limited financial resources and no contacts within the black community, Paramount relied on J. Mayo Williams and regional record distributors to enlist talent and advertise their records in the black press.

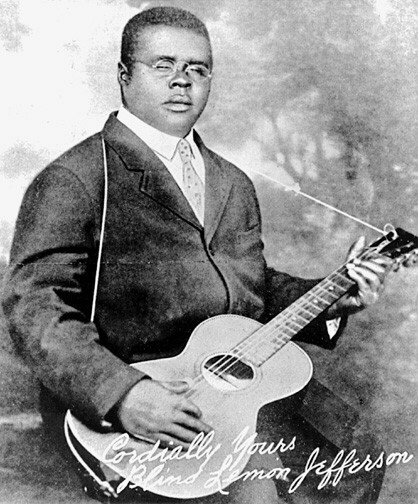

Williams was originally from Arkansas and had attended Brown University. After graduation, he moved to Chicago, where he wrote for the black weekly newspaper The Chicago Whip. Williams’ heart was in music, especially blues. Despite having no experience in the record industry, Williams applied to Paramount Records as a talent scout and recording session supervisor. Impressed by his enthusiasm, Paramount hired Williams in 1923, where he eventually the company’s first and only black executive. Williams, responsible for recruiting artists from around the United States to record for Paramount, had a special ear for the newest trends in black music. Through his contacts in Chicago and the American South, Williams discovered artists such as Papa Charlie Jackson, Priscilla Stewart, Ida “Queen of the Blues” Cox, and Ma Rainey. His most important discovery, however, was Blind Lemon Jefferson, who produced such hits as “Long Lonesome Blues” and “Piney Woods Money Mama.”

Like most other record companies in the 1920s, Paramount frequently paid their black artists considerably less than white performers. According to historian Stephen Calt, the Port Washington-based company received the dubious honor of becoming one of the most exploitative record labels in the field, successfully institutionalizing the cheating of its artists. Contracts that allowed Paramount to recoup their recording costs meant that nine out of ten Paramount recording artists never received royalties for their recordings or performances. In addition, Paramount often required artists to waive their copyrights on their written material, allowing Paramount to receive publishing royalties if another record company ever reissued the artist’s song. Williams himself was guilty of manipulating talent, oftentimes deducting “finders fees” from artists he had discovered.

Written by Sergio M. González.

SOURCES

Filzen, Sarah. “The Rise and Fall of Paramount Records.” The Wisconsin Magazine of History 82:2 (Winter, 1998-1999): 104-127.

Komara, Edward. “Blues in the Round.” Black Music Research Journal 17:1 (Spring, 1997): 3-36.

Springer, Robert. “Commercialism and Exploitation.” Popular Music 26:1 (Jan. 2007): 33-45.

Van der Tuuk, Alex. Paramount’s Rise and Fall. Denver: Mainspring Press, 2003.

Featured image: Louis Armstrong performing in Amsterdam October 29, 1955. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

RELATED STORIES

The Wisconsin Chair Company

Paramount Records

The Record Production Process

OBJECT HISTORY: Paramount Records 78