Located near the heart of Grafton, WI, a rusted power wheel sits on the steep west bank of the Milwaukee River. Despite its corroded appearance, this metal device once powered an entire factory responsible for pressing popular shellac records.

The history of this wheel parallels that of the town. In 1848, only two years after Grafton was founded, craftsmen built shops near the river, where a new dam allowed them to harness water power for industrial purposes.[1] Eventually, the Wisconsin Chair Company purchased one of these industrial buildings, which became the manufacturing home to its musical subsidiary, Paramount Records. From its first day until its last, Paramount relied on the adjacent river’s flow, using the water wheel to power its record pressing plant.[2]

The process of pressing these Paramount records resembled making waffles with an iron. An often inconsistent mixture of ingredients — powdered china clay, shellac, and stone[3] — would be heated by large hot plates. These warmed sheets were then set into presses, which were initially hand-operated but eventually made hydraulic. Once labels had been attached by hand, the press was closed, and cold water was poured to cool the new record.[4] In the absence of electric motors, all of these operations, barring those done by hand, depended on the water wheel for power. Spun by the current of the Milwaukee River, the wheel turned a rope drive, a mechanical pulley system used to transmit power. Just six spans powered the entire plant, which could manufacture up to 28,000 records per day.[5]

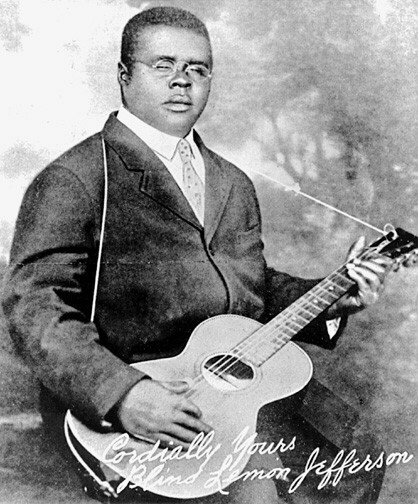

From 1929 to 1932, the wheel powered the pressing of one-fourth of all ‘race records’ — blues, jazz, gospel music — traditionally marketed to African American audiences in the United States.[6] For its role in the factory’s impressive output alone, the wheel is an unsung hero in popularizing African American artists and their recordings. The prominence of these musicians is also noteworthy: Charlie Patton, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Ma Rainey, Skip James and Son House all recorded with Paramount, along with many other famous names.

Despite its centrality to the company’s production, the power wheel was also a factor in Paramount’s closure. The water power that drove the record plant was less efficient than the electric factories operated by Paramount’s competitors, contributing to the company’s closure in 1932.[7] Although it has since been left to rust, the power wheel stands today as a reminder of all the historically notable records that originated here in Wisconsin.

Written by Daniel Prohuska, December 2020.

FOOTNOTES

[1]Alex Van Der Tuuk, Paramount’s Rise and Fall: A History of the Wisconsin Chair Company and Its Recording Activities (Denver, CO: Mainspring Press, 2003), 30.

[2] Alex Van Der Tuuk, “(P)Redating Grafton’s L-Matrix Series,” accessed December 18, 2020, http://www.vjm.biz/articles11.htm.

[3] Van Der Tuuk, Paramount’s Rise and Fall, 34.

[4] Ibid, 38-39.

[5] Ibid, 39.

[6] Ibid, 38.

[7] Melinda Roberts, “Grafton Paramount Plaza: Paramount Records Legacy,” Wisconsin Historical Markers, accessed December 18, 2020, http://www.wisconsinhistoricalmarkers.com/2015/04/grafton-paramount-plaza-paramount.html.

[8] Van Der Tuuk, Paramount’s Rise and Fall, 39.