Influential Leaders

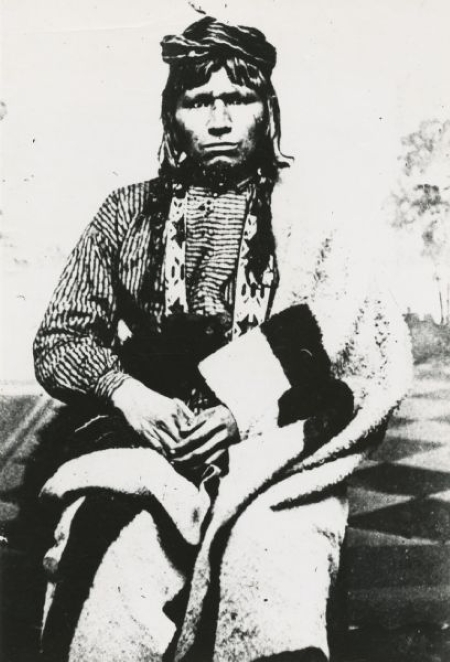

Chief Simon Kahquados

Chief Simon Onanguisse Kahquados was the last hereditary descendant in a long line of Potawatomi chiefs, his family being one of the oldest known Potawatomi inhabitants of Wisconsin. An engaging speaker, Kahquados often served as an interpreter and provided a wealth of information to the Wisconsin Historical Society regarding traditional Potawatomi culture and history.

OBJECT HISTORY: Potawatomi Beaded ‘Soldier Coat’

As an elder spokesman for the Potawatomi Indians, Chief Simon Onanguisse Kahquados made a number of trips to Washington, D.C. in the early twentieth century in an effort to regain land that his people had lost through treaties with the United States government in the 1800s. Kahquados wore this coat on his last trip to Washington, as well as on other important occasions.

Ke-che-waish-ke

Ke-che-waish-ke (1759 – 1855), also known as Chief Buffalo, Peezhickee, and Le Boeuf, led the Lake Superior Ojibwe people of La Pointe, the location of Madeline Island today. Ke-che-waish-kewas instrumental to signing treaty agreements between the Wisconsin Ojibwe people and the United States, beginning with the treaty of 1825 and ending with the treaty of 1854.

OBJECT HISTORY: Ojibwe Presentation Pipe

This Ojibwe presentation pipe consists of two pieces: a pipe bowl and a pipe stem. It was most likely for spiritual ceremonies. According to the Wisconsin Historical Society, the pipe bowl is carved from heavy stone, and has two common images to Native American art works: the Janus head, which is two heads facing back to back, and a small buffalo figure.

Ogimaa Weigiizhig

Ogimaa Weigiizhig (Chief Big Sky), son of Ah-mous (translated either as Little Bee, or Thunder of Bees), was an ambitious and influential leader. In the 1850s, he came into possession of an eaglet—by some accounts the group had cut down a tree unaware that there was an eagle’s nest, and Ogimaa Weigiizhig rescued the eaglet; by other accounts he had seen the eagle’s nest, climbed the tree to steal the eaglets, and was made to kill the mature eagle that attacked protecting it’s young. In any case, this Ogimaa Weigiizhig came to have the eaglet that would grow to be known as Old Abe.

OBJECT HISTORY: Feather from Old Abe the War Eagle

A bald eagle feather that represents one of the few remaining parts of perhaps the most famous Bald Eagle in our nation's history: Old Abe.

Treaties and Missionaries

Missionaries and Land Rights: The Story of Erik Morstad and the Potawatomi

The following story about the Potawatomi and Reverend Erik Morstad is a relatively well-known one: a missionary acted as a heroic figure who gifted the Potawatomi land that had always been rightfully theirs. But what happens when we revisit this written account with a questioning eye and consider alternative interpretations based on the same information?

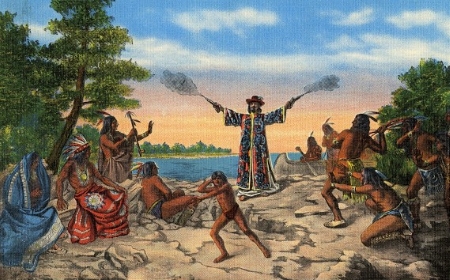

French Wisconsin at Fort la Baye

French explorers, voyageurs (fur traders), Jesuit priests, and other settlers began arriving in the Upper Great Lakes region of North America in the mid-1600s. Jean Nicolet supposedly landed near present-day Green Bay, Wisconsin in 1634, naming the waterway La Baye des Puants, literally “Bay of Bad Odors.”It was not until the 1680s, however, that the French would gain a firm foothold in the territory, led primarily by commandant Nicholas Perrot, and the Jesuit priest Claude Allouez.

The Fur Trade Era

OBJECT HISTORY: Trade Blanket

Not long after the explorer Jean Nicolet first set foot in Wisconsin, French traders saw an opportunity to make money by sending beaver furs back to Europe for use in stylish coats and hats. Instead of hunting the beavers themselves, these traders acquired the furs from the native people of Wisconsin who had experience collecting the pelts. And instead of paying money for the furs, the French offered to trade items such as metal pots, guns, axes, glass beads – and blankets.

OBJECT HISTORY: A Hudson’s Bay Co. Point Blanket Coat

This wool coat was constructed from a ‘point blanket’ made by the Hudson’s Bay Company, likely during the early 1920s. A Wausau businessman wore it at one of the town’s early Winter Frolics, an annual winter sports festival that attracted tourists from as far as Chicago. The businessman belonged to a group of local business…

OBJECT HISTORY: Beaver Felt Hat

The beaver felt hat was one of the main reasons for the success of the fur trade in northern states, such as Wisconsin, and in Canada. But why was this hat more popular than others? For Europeans in the 16th century, a broad-brimmed felted beaver hat was considered the latest ‘fad’ or fashion trend and was a “social necessity”.

Ancestral Wisconsin

OBJECT HISTORY: Aztalan Copper Maskettes

Found at the Aztalan archaeological site in southeastern Wisconsin, these small copper artifacts were most likely used as ornate jewelry. Specifically, Mississipian people likely wore the mask-shaped copper designs as earrings. Although Native Americans seldom used metal, they sometimes used metals from the copper deposits found in the Great Lakes region to make tools and ornamental pieces like these 5.8 x 4.6 centimeter earrings.

OBJECT HISTORY: Aztalan Fishing Weir

Although much of the village of Aztalan has been gone for hundreds of years, this fishing weir still remains in the Crawfish River. These stones and boulders were left behind by the glaciers 10,000 years ago and were later used by the Mississippians to create their weirs.

When Lake Koshkonong was a Marsh

Before the lake was created by European settlers, several Native American tribes used the area that would become Lake Koshkonong for purposes of food, water, and shelter. There was fresh water for drinking, cooking, and attracting animals to the area. The area hosted an abundance of wild rice and celery, and these in turn brought a huge wild duck population for hunting. Because of the abundance of resources, the area became a meeting place for several Native American nations.

Wisconsin’s Ancient History in the Kickapoo Valley

If you look closely, the landscapes around us tell stories about the past. Sometimes in the curve of a road, a line of trees, or stretch of prairie careful observers can find evidence of the people and animals that used to call a place home. Because people have called Wisconsin home for roughly 12,000 years, in some parts of the state the landscape can tell very old stories.

Lifestyle

OBJECT HISTORY: Cradleboard

Native Americans used cradleboards in North America to protect, carry, and entertain their babies. Cradleboards allowed women to keep babies close to their side. Women carried cradleboards on their backs. They also could rest them against a tree. The cradleboard protected babies from danger and kept them happy.

OBJECT HISTORY: Ricing Sticks (Bawa’iganaakoog)

Bawa’iganaakoog, threshers, or knockers, are all words used to refer to the sticks used for the harvesting of wild rice. Wild rice holds extreme cultural importance to Ojibwe culture for several reasons beyond basic sustenance; not only can it be dried and stored to sustain people through the winter, but it was also seen to fulfill the prophecy that guided the Ojibwe people west to what is now their home.

OBJECT HISTORY: Ojibwe Presentation Pipe

This Ojibwe presentation pipe consists of two pieces: a pipe bowl and a pipe stem. It was most likely for spiritual ceremonies. According to the Wisconsin Historical Society, the pipe bowl is carved from heavy stone, and has two common images to Native American art works: the Janus head, which is two heads facing back to back, and a small buffalo figure.