Some histories are not as straightforward as others, especially when cultures collide. It may come as no surprise that stories about the interactions between Native Americans and white settlers are sometimes one-sided. We can partly attribute this to the European tradition of written histories, which we heavily rely on to decode the past. The following story about the Potawatomi and Reverend Erik Morstad is a relatively well-known one: a missionary acted as a heroic figure who gifted the Potawatomi land that had always been rightfully theirs. But what happens when we revisit this written account with a questioning eye and consider alternative interpretations based on the same information?

In the story of the Potawatomi and Rev. Erik Morstad, we know two things as facts. Firstly, the Potawatomi of Forest County Wisconsin acquired funds from the United States Federal Government in 1913 to buy land for a reservation. Secondly, Norwegian Rev. Erik Morstad assisted the Potawatomi’s lobbying efforts by connecting the Potawatomi with a lawyer. Equipped with this information, the main writer of Morstad’s life, his own son Alexander E. Morstad, came to the conclusion that his father played a critical role in the creation of the Forest County Potawatomi reservation. The Potawatomi echoed this conclusion in the “Timeline of Potawatomi History” on their own website. While the fact that Morstad helped the Potawatomi create a reservation in Forest County remains true, the history of Morstad’s relationship with the Potawatomi can be explained better by taking a more critical look at his intentions in working with the Potawatomi. Through his missionary efforts in working with the Potawatomi, Rev. Erik Morstad both assisted the Potawatomi goal of gaining a federally recognized reservation and perpetuated the systematic destruction of Potawatomi culture.

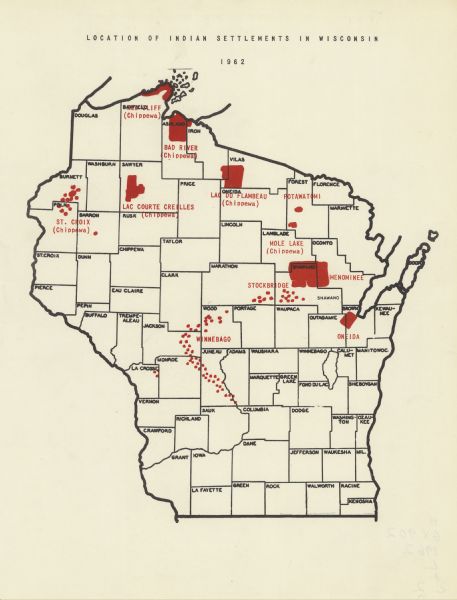

The history of Erik Morstad’s involvement with the Potawatomi depicts him as an exemplary missionary and friend of the Potawatomi. In one journal written by his son and main biographer, Alexander E. Morstad, he writes that his father’s efforts “proved exceedingly fruitful to a band of 700 Potawatomies.” In many ways this sentiment is true. The Potawatomi had been split by the Treaty of Chicago in 1833. Some Potawatomi followed the treaty and moved to Oklahoma while another group split off, fleeing north. Morstad stumbled upon this group of Potawatomi in Northern Wisconsin. To gain inroads into the community, Morstad helped some members of the Potawatomi gain homesteads in 1894 via the Indian Homestead Act of 1884. This marked some of the first land ever gained by this northern branch of Potawatomi, and the Potawatomi specifically cite Morstad on their website as the man who made this possible. Morstad became even more important to the Potawatomi’s efforts to acquire a federally-recognized reservation. The Potawatomi had been sending members to Washington as early as 1894, but their efforts yielded no results. However, the big break in the Potawatomi’s efforts to gain a federally-recognized reservation happened once Morstad reached out to the Minnesota Senator Knute Nelson who referred him to attorney R. V. Belt. Though reluctant at first, Former Commissioner of Indian Affairs R.V. Belt helped the Potawatomi by using his connections to the federal Indian Office. His efforts resulted in the Federal Government formally recognizing the Forest County Potawatomi band in 1908. And, while Belt died in 1910, his work also resulted in the Federal Government granting the Potawatomi $25,000, which was used to buy the 11,786 acres that now make up the Forest County Potawatomi Reservation. Therefore, Morstad’s political privilege set a series of events into motion that resulted in the creation of the reservation. This is not to assert that without Morstad the Potawatomi could not have even gotten a reservation or that their efforts did not contribute to the creation of the reservation. However, it is clear that Morstad’s arrival in Forest County unequivocally helped the Potawatomi reach their goal of creating a home in Forest County which had borders that would be respected by the Federal Government.

While Morstad helped the Potawatomi gain land, there also must be an evaluation of Morstad’s reasons for coming to the Potawatomi in the first place. Morstad worked as a missionary and was sent to the Potawatomi with the goal of convering the Potawatomi into Christians above all else. Thus, Erik Morstad perpetuated the destruction of Potawatomi culture by trying to impress the gospel on the Potawatomi and “educate” them in new schools. In journal entries printed by Morstad’s son, his mindset for going to Forest County is clear. Morstad wrote that “there are many horrible customs among [the Potawatomi].” Here, Morstad displays his disgust with the Potawatomi for practicing tribal customs. This reflects his own racism and desire to put an end to these practices. Then, he may have called it missionary work. Today, we would call this ethnocide as Morstad wanted to go into this community with the expressed goal of replacing Potawatomi cultural practices with Christianity. It’s even more clear that Morstad wanted to fundamentally change Potawatomi culture considering his main project in Forest County was a school. In his school, Morstad taught the gospel and tried to convert the Potawatomi to Christianity. In fact, Morstad wrote back to the synod sponsoring his mission that he would attempt to convert the Potawatomi one by one. While Morstad’s school remained small, he expressed his desire to create an “industrial” school. Such an “industrial school” would have acted like other Native American boarding schools of the time that forcefully assimilated indigenous children into white American society, such as the infamous Carlisle Industrial School. Therefore, it’s possible that with more funding Morstad could have been remembered as a man who wanted to continue the reeducation campaign that had been forcibly pushed upon Native Americans throughout the 1800s and 1900s.

Historical absolutes are very hard to come by. Erik Morstad had been previously presented in the historical record as a friend and important ally for the Forest County Potawatomi. The Potawatomi’s own telling of their history on their website makes clear that they believe he was integral to creating their reservation. However, Morstad’s relationship was very typical of many relationships between missionaries and Native Americans during this time. Therefore, in conjunction with the political assistance he provided to the Potawatomi, Morstad should also be remembered as a man whose goal of Christianizing the Potawatomi reflected his negative judgement of indigenous peoples.

Written by Jack Styler, August 2020.

SOURCES

A.E. Morstad, “Erik Morstad’s Missionary Work among Wisconsin Indians,” NAHA // Norwegian-American Studies, accessed July 23, 2020, https://www.naha.stolaf.edu/pubs/nas/volume27/vol27_7.htm.

“Forest County Potawatomi.” Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction, September 20, 2018. https://dpi.wi.gov/amind/tribalnationswi/fcp.

“Forest County Potawatomi.” Wisconsin Historical Society. March 10, 2015. https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS4361

“Timeline of Potawatomi History.” Forest County Potawatomi. https://www.fcpotawatomi.com/culture-and-history/timeline-of-potawatomi-history/