Although the area surrounding Lake Koshkonong is now home to the towns of Milton, Edgerton, and Fort Atkinson, the region looked very different before the middle of the nineteenth century. The lake itself did not exist until 1851 with the creation of the first Indianford Dam, which turned the marsh land into the lake of today. Before the lake, early European settler Lucien B. Caswell described the marshland as a flowing stream so densely packed with wild rice and celery that it was hard to even navigate in a canoe.

Before the lake was created by European settlers, several Native American tribes used the area that would become Lake Koshkonong for purposes of food, water, and shelter. There was fresh water for drinking, cooking, and attracting animals to the area. The area hosted an abundance of wild rice and celery, and these in turn brought a huge wild duck population for hunting. The reeds could also be used as a material to craft shelters and sleeping mats. The marshland allowed for easy transportation by boat. Because of the abundance of resources, the area became a meeting place for several Native American nations.

Earliest Settlement

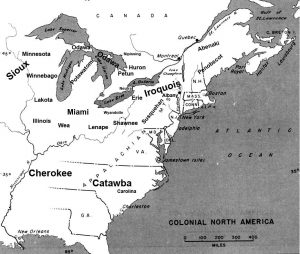

People have been living along the shores of Lake Koshkonong for a very long time. From archeological evidence, several Native American cultures inhabited the area surrounding Lake Koshkonong since roughly 10,000 B.C.E. Burial mounds in the area show that people from the Woodland and Mississippian Cultures occupied the area around the lake and placed great value in the land. By the fifteenth century, several Native American tribes had strong roots in the Lake Koshkonong region, including the Potawatomi, Sauk, Meskwaki, and Ho Chunk nations.

A New Home After War

Over the several centuries before the treaty-making era, control over the Lake Koshkonong region changed hands between native powers many times. However, the Ho Chunk and Potawatomi tribes are often most associated with the lake itself because they lived near the shores of the marsh during the first European settlement in the region.

The Potawatomi were relative newcomers to the area around Lake Koshkonong. Originally living in northern Michigan, the Potawatomi settled in the region after the end of the French and Iroquois Wars. The French and Iroquois Wars, also known as the Beaver Wars, were a series of wars during the seventeenth century in which the Iroquois tried to take control of the lucrative fur trade. After a series of defeats, the Potawatomis, like many other Algonquin-speaking tribes such as the Ojibwe, fled the conflict by moving west into the upper Great Lakes region. By 1820, it is estimated that around 10,000 Potawatomi people lived in the region that would become Jefferson County.

Meanwhile, the Ho Chunk also called Lake Koshkonong home. The lake played a large role in the Ho Chunk peoples’ traditional food practices, and members of the nation visited the lake annually to hunt and gather. The Ho Chunk established one permanent settlement on the shores of Lake, White Crow Village at Carcajou Point on Lake Koshkonong. This village was a place of permanent residence, but had a varying amount of residents at any given time and was a gathering place for the tribe.

French fur-traders recorded the first European accounts of the region that would become Lake Koshkonong. Charles Gautier de Verville arrived first in January of 1778, traveling from what is now the Green Bay area looking for potential sites for new fur trading posts. Joseph Thiebeau Cavelle, Charles Poe, and Elleck de Mar followed his path in 1785 and established cabins along the shore of Lake Koshkonong, however these early settlers were primarily interested in fur trading.

After the Revolutionary War, the newly-formed United States gained control of the region, and attempted to govern settlement and trade in the territory through The Northwest Ordinance of 1787. Though fur trading continued to play a part in the regional economy, the fur trade had begun a sharp decline and was replaced by settlers interested not in trade but in acquiring land.

Cultural Persistence and Lake Koshkonong

For these new settlers, land was their primary focus instead of fur trading. One early settler, Lucien B. Caswell, described the land “as a vast meadow” and declared that “no more beautiful landscape was ever painted.” Apart from the beauty of the land, it also held important potential for the establishment of towns and the utilization of important resources, like the wildlife and water sources.

A Treaty in 1829, known as the Third Treaty of Prairie du Chien, ceded most the Wisconsin land claimed by the Ho Chunk and other native peoples to the United States, including the land around Lake Koshkonong. In exchange, the United States promised the Ho Chunk yearly annuity payments for thirty years, an immediate payment of $30,000 dollars ($813,374 in 2018 dollars), and an agreement to maintain the Fox and Wisconsin river portage. A law from 1895 further barred the Ho Chunk from returning to the shores of the lake.

Despite such laws, however, many Ho Chunk people continued to make pilgrimages to Lake Koshkonong, even after the land of lush reeds had been transformed into one of the largest lakes in Wisconsin with the creation of the larger Indianford Dam in 1932. Maintaining practices like an annual visit to Lake Koshkonong to hunt and harvest food is an important way for indigenous knowledge and culture to be passed-on to the next generation.

To learn more about plants, foodways, and Native American cultural revitalization, listen-in on Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer’s interview with Wisconsin Public Radio about her book Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teaching of Plants. Dr. Kimmerer is a member of the Potawatomi Nation and her interview touches on many of the historical events discussed in this post and their consequences for subsequent generations.

Featured image: a man and a woman harvesting wild rice in 1922. Image courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society, image ID 133699.

Written by Lauren Drapes.