French mariners and explorers using the Le Maire Sundial Compass depended on both their own specialized navigational expertise and maps produced by French cartographers. Many such maps were created based on explorer accounts of the navigable waterways between the Atlantic Ocean to the Mississippi River.

Samuel de Champlain (1567-1635) was perhaps one of the most important leaders in the history of French exploration and mapmaking in North America. Born in the port region of Hiers-Brouage of western France, Champlain later earned a reputation as a skilled navigator and cartographer. Beginning his exploration of North America in 1603, Champlain went on to reveal for his countrymen the source of the St. Lawrence River and the extent of the Great Lakes. His map Carte Geographique de la Nouvelle France, published in 1612, became, along with subsequent maps, a preeminent resource for understanding the landscape of New France in the seventeenth century.

Indeed, these maps were critical for the earliest waves of French voyageurs and Jesuit missionaries as they navigated the western shores of Lake Michigan and Green Bay. These explorers came aboard canoes, shallow-draft bateaux, and eventually, in the late 1670s, decked ships.

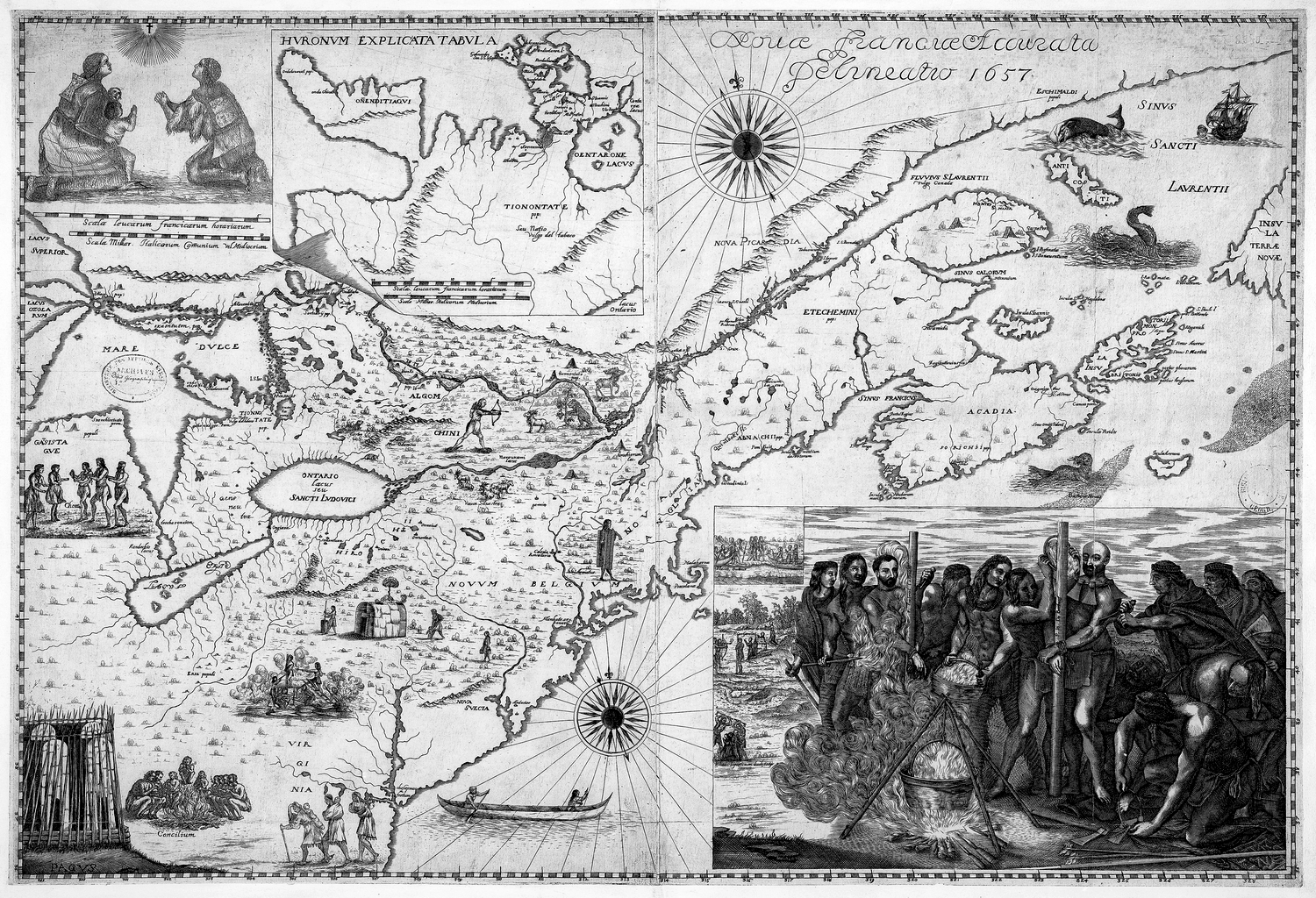

But while Champlain and his contemporaries’ maps were indispensable for explorers, they were not always exact. Jesuit missionaries took it upon themselves to draft more accurate maps, which they began producing with exquisite detail. Jesuit Francesco Bressani’s 1657 manuscript map of New France is one of the most decorative seventeenth-century maps of the region. Other Jesuit maps, like Father Francois du Creux’s 1660 Tabula Novae Franciae, and Father Rene Brehant de Gallinee’s 1670 Carte du Lac Ontario proved invaluable for the region’s growing fur trade and evangelization in the western Great Lakes

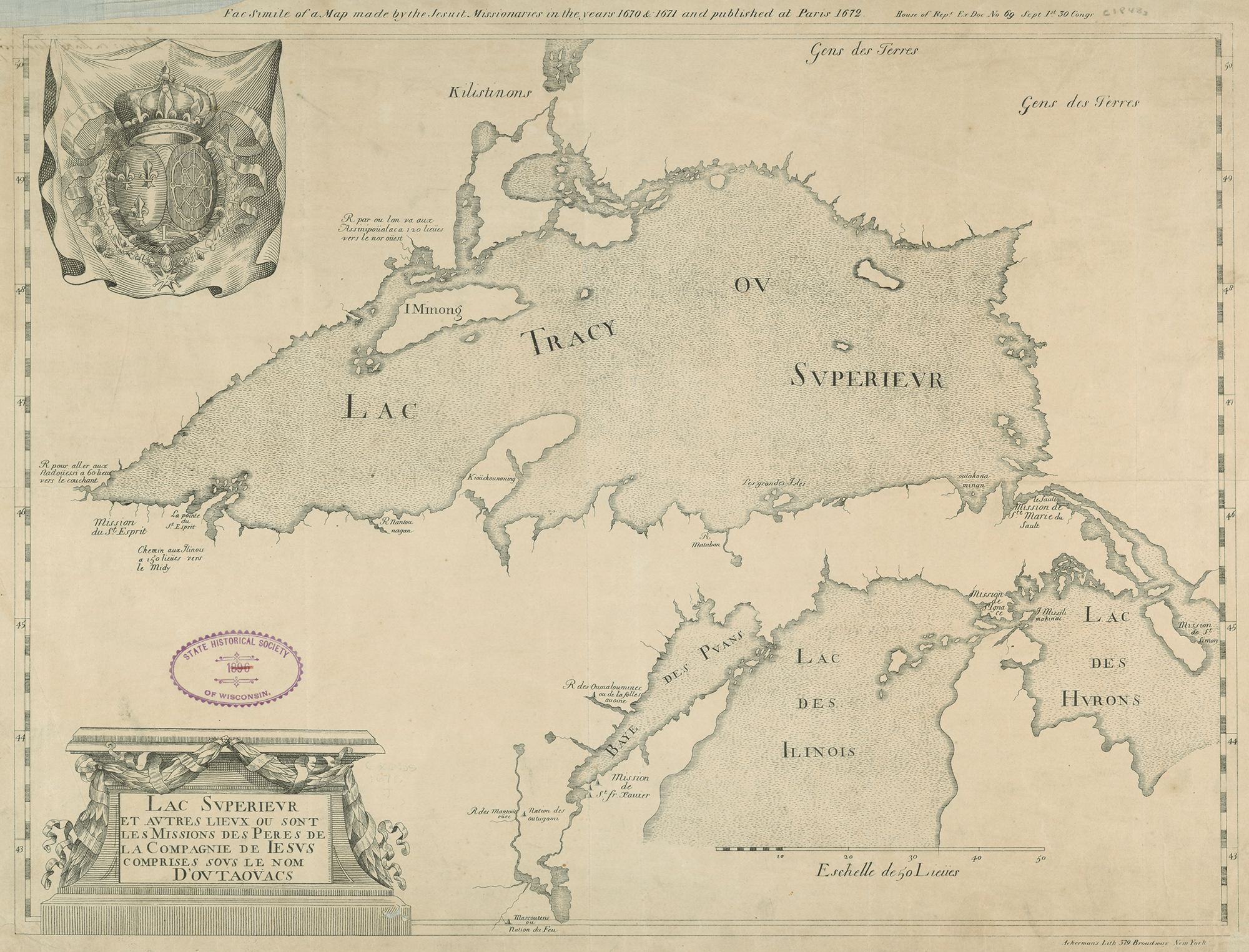

By the end of the seventeenth century, northeast Wisconsin was rapidly falling under French influence. This cultural and spiritual transformation was partially cultivated by Father Claude Allouez at his mission of St. Francis Xavier, near what is now De Pere, Wisconsin. The St. Francis Xavier mission, as well as others established throughout New France, were marked by Father Claude Dablon on his widely publicized Jesuit Map of 1672.It was this map, along with improved navigation equipment, that allowed Louis Jolliet and Father Jacques Marquette to reach Green Bay and ultimately the Mississippi River for the first time. This expedition paved the way for further exploration, aided by devices like the Le Maire Sundial, into the North American interior via Green Bay, ushering in a new era of colonial expansion that ultimately transformed the cultural and political landscape of Wisconsin forever.

Written by Kevin Cullen, October 2017.

SOURCES

Heidenreich, Conrad. “Seventeenth Century Maps of the Great Lakes: An Overview and Procedures for Analysis.” Archivaria No. 6 (1978): 83-112.

Kellogg, Louise Phelps. The French Regime in Wisconsin and the Northwest. Madison: The State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1925.

Steuer, Mark. “The Mapping of the Great Lakes in the Seventeenth Century” Voyageur Magazine Vol. 1, No. 1 (1984): 34-42.

Featured image: Samuel de Champlain’s “Carte Geographique de la Nouvelle France,” first published in 1612.