The village of Williamsonville was first founded by brothers Fred and Tom Williamson who ran Door County’s largest shingle mill. The village was home to 77 residents and sat on less than 10 acres of land at the time of the fire. Most of the residents were either members of the Williamson family or were employees at the mill.

Of the 77 residents, 60, including Miss Maggie Haney, were killed by the Peshtigo fire. The 17 survivors were left with burnt hands, eyes, and feet. The village they once called home, as well as their family members and friends, were gone.

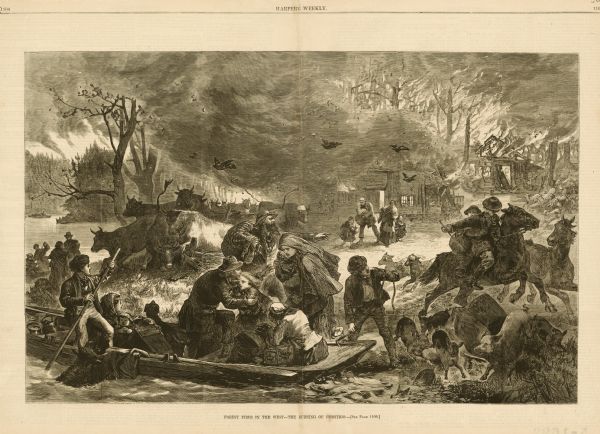

Williamsonville was never rebuilt after the devastation of the Peshtigo Fire. In 1927, Tornado Memorial Park was established at the site of a well where 7 men hid from the fire tornadoes that ravaged through the village. The fire tornadoes or fire vortices were created by the winds over northeastern Wisconsin at the time of the fire. The vortices contributed greatly to the speed of which the fire spread.

Although the fire was incredibly devastating to those who called Williamsonville home, it also transformed the economy in that region. The area that was once used for lumbering eventually became rich farmland. The fire cleared any remaining forests and opened the land to farmers who were able to grow crops. Today, the Peshtigo Fire is seen as the main cause of southern Door County’s quick transition from lumbering to agriculture. In the 1870 and 1880 censuses of the southern Door County townships most affected by the fire, there were great increases in overall population, number of farmers, and cultivated land area.

Written by Morgan Zdroik, July 2020.

SOURCES

Sarah Derouin, “Benchmarks: October 8, 1871: The Deadliest Wildfire in American History Incinerates Peshtigo, Wisconsin.” EARTH Magazine, 19 September 2017. Accessed 5 December 2019. https://www.earthmagazine.org/article/benchmarks-october-8-1871-deadliest-wildfire-american-history-incinerates-peshtigo-wisconsin.

History.com Editors, “Chicago Fire of 1871.” History.com, 4 March 2010. https://www.history.com/topics/19th-century/great-chicago-fire.

Tom Hultquist, “The Great Midwest Wildfires of 1871,” National Weather Service. https://www.weather.gov/grb/peshtigofire2

Joseph M. Moran and E. Lee Somerville “Tornadoes of Fire at Williamsonville, Wisconsin, October 8, 1871.” Transactions of the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters Vol. 78, 1990.

John J. Pauly, “The Great Chicago Fire as a National Event.” American Quarterly 36, no. 5 (1984): 670. doi:10.2307/2712866.

Peter Pernin, “The Great Peshtigo Fire: An Eyewitness Account.” The Wisconsin Magazine of History 54, no. 4 (1971): 246-72. www.jstor.org/stable/4634648.

Peshtigo Fire Museum, “History of the Peshtigo Fire,” Accessed 5 December 2019. http://peshtigofiremuseum.com/fire/.

Justin Skiba, “The Fire That Took Williamsonville,” Door County Pulse, 2 September 2016. https://doorcountypulse.com/fire-took-williamsonville/

Wisconsin Historical Society, “October 8, 1871, the Night Peshtigo, Wisconsin was Destroyed by Fire,” Historical Essay. https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS2911

Wisconsin Historical Society, “Peshtigo Fire,” Historical Essay. https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS1750.

This Post Has 2 Comments

Comments are closed.

where are the victims of Williamsonville buried?

There is a memorial to all of the victims of the Williamsonville fire at Tornado Memorial Park in Door County. According to a newspaper article from page 4 of The Advocate published in Sturgeon Bay reported:

It goes on to say:

Many of the victims were reinterred at St. Joseph’s Cemetery in Sturgeon Bay. Some bodies were claimed and laid to rest elsewhere. The Ahearn brothers, for example, were reinterred at St. Mary’s Cemetery in Forestville. Miss Maggie Heaney, the owner of the breastpin featured on our site, was buried at Bayside Cemetery north of Sturgeon Bay. The Williamson family was reinterred at Woodlawn Cemetery in Green Bay.