Located on the Wisconsin River, Wausau developed as a logging town in the 1830s. George Stevens chose the site because of the waterfall that spanned the river, which provided power for sawmills used to turn the felled trees into lumber. The waterfall, Big Bull Falls, was one of the most powerful waterfalls along the Wisconsin River. The logging town that sprang up around the sawmill was originally named for the falls, but lumber baron Walter McIndoe changed the city’s name in 1850 to “Wausau.” In Ojibwe, the name means “far away place.”[1]

Logging outfits and German immigrants hoping to work for the logging companies moved to the area, and the town’s population boomed. In 1872, the State of Wisconsin granted Wausau a city charter. Despite the best efforts of conservationists like Edward Merriam Griffith, Wisconsin’s first state forester, lumber businessmen and legislators from northern Wisconsin succeeded in shutting down all forestry programs other than fire prevention within the state. This lack of protection enabled loggers to quickly deplete the resource their businesses depended upon.[2]

As the logging industry accelerated, Wausau flourished. However, its dependence upon logging also meant that when short-sighted businessmen over-harvested, the soft pines and logging declined and so too did the town of Wausau.[3] The logging industry in Northern Wisconsin began to decline around the turn of the century.

Reviving Wausau

As the logging industry moved toward collapse, sharp-minded business owners in the town pooled their resources and ideas in an effort to redefine the area’s economy. Although they came to Wausau for the soft pines and the profits, the businessmen stayed long after they had cut down the trees. These businessmen were known as the Wausau Group.

Though the Wausau Group remained in Wausau, their business interests were spread across a wide area and many industries. For instance, their business included logging in other regions of the U.S., pulp mills in the Wisconsin River Valley, and insurance. For instance, one member of the group, Cyrus Yawkey, invested in logging companies across the United States where other varieties of pine were still plentiful. These include Arkansas, Louisiana, and the Pacific Northwest. Despite this, Yawkey chose to settle in Wausau and maintained many investments in central Wisconsin. As the lumber industry declined, other members of the Wausau Group found ways to continue making money from the forests in Wisconsin like running pulp mills.[4]

Still other members of the Wausau Group capitalized on new Wisconsin-based industries. Neal Brown, a forward-thinking lawyer, organized Employers Mutual Liability Insurance, which took advantage of the newly signed worker’s compensation laws of 1911. The company was a success and supported other businesses in the area. One of their first large clients was the new Mosinee Mill, one of the pulp mills founded by the Wausau Group.

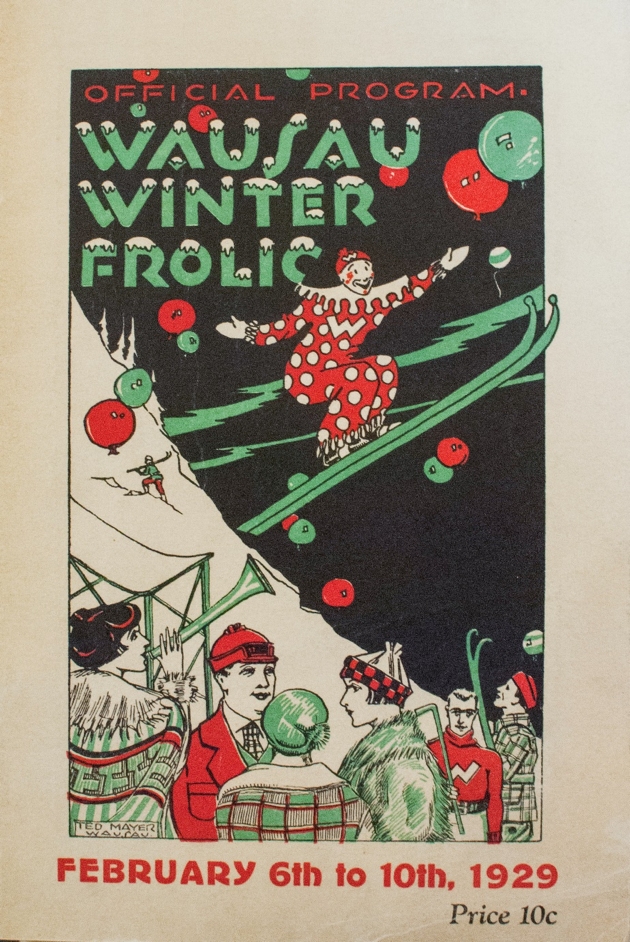

As the years passed, the Wausau Group helped the region transition away from logging in other ways. For instance, they constructed a hydroelectric dam across the site of Big Bull Falls and built an airport on the south side of the city. They founded clubs for sports and socializing, and became local tourism boosters to attract new residents to Wausau.[5] In doing so, the Group cultivated a common local identity around winter activity and northern life. They consciously tried to connect Wausau to an authentic, rugged outdoor lifestyle so many urbanites in Chicago and Milwaukee sought. To do this, member of the Wausau Group played-up their connection to the pre-logging history of Wisconsin, including the fur trade.

This informal network of wealthy, intelligent men was determined to diversify the economy to keep wealth in the region.[6] These men were heavily invested in the area, and sought to develop more than the economy.

Written by Anna Wright, February, 2018.

FOOTNOTES

[1] Robert Mentzer, “How Wausau Got Its Name,” Wausau Daily Herald, 2015.

[2] Wisconsin Conservation Hall of Fame (1998: Stevens Point; Wisconsin Forester’s Association)

[3] Wisconsin Hometown Series: Wausau (2011; Wisconsin Public Television)

[4] Cyrus Carpenter Yawkey, “Companies File,” (Cyrus Carpenter Yawkey and Aytchmonde Perrin Woodson Papers, 1887-1957, Stevens Point), accessed April 2017, http://digital.library.wisc.edu/1711.dl/wiarchives.uw-whs-stpt00ag

[5] Ibid.

[6] Wisconsin Hometown Stories: Wausau (2011: Wisconsin Public Television)

Marathon County Historical Society

Research for this object and it’s related stories was supported by the Marathon County Historical Society in Wausau, Wisconsin.

RELATED STORIES

Emelie Manthei’s Point Blanket Coat

OBJECT HISTORY: A Hudson’s Bay Company Point Blanket Coat

The Wausau Winter Frolic: Wausau’s History as a Sports Capital