Alcohol consumption is an integral and often contentious facet of American life and has been for most of the nation’s history. In the 1800s, the public believed alcohol had medicinal properties and regulated health. However, the harmful effects of drunkenness on the body and personal relationships became increasingly more obvious as the decades churned on. Determined to eliminate alcohol from American society, temperance organizations rose to prominence and in the 1830s and 40s. In particular, the latter half of the 1840s proved to be politically fruitful for the movement, which established itself as a political power during those years. In Baraboo, local chapters of the Washingtonian Society, the Sons of Temperance and home-grown organizations like the Baraboo Total Abstinence Societie were a testament to this rise. Notably, these societies included women in their membership, with later groups like the Daughters of Temperance comprised solely of women.

In this era, women were expected to be the moral compass of the family, which included shaping their husbands’ behavior to conform to societal norms. Social norms and standards were also shaped by a preoccupation with godliness amongst certain religious groups like Methodists, Congregationalists and Presbyterians. Therefore, if a man was a drunk, it reflected poorly on his wife because she was responsible for ensuring his respectable and godly behavior. Despite the allure of alcohol, Baraboo women of the 1840s were widely successful in keeping men home and away from taverns and spirits. As a result, alcohol consumption decreased in the 1840s. However, the efficacy of moral suasion was tentative at best, with many men more than willing to jump ship and abandon temperance.

Beginning in the 1850s, alcohol consumption surged. This shift is often attributed to a statewide influx of German immigrants, some of whom settled in Baraboo. The growth of a pro-liquor German population weakened the temperance movement’s power in the state legislature and enabled less stringent alcohol laws to replace stricter temperate law. Additionally, other local factors contributed to this rise. Before the railroad reached Baraboo, major commercial centers were many miles away. The difficulty and cost of transporting products long distances was so great that it was more cost-efficient to brew beer and sell it locally than it was to carry wheat and barley to market. This meant more drinking amongst members of Baraboo’s working class. The working-class men of Baraboo began their day with a drink to open their eyes, followed by a palate cleanser before noon, another drink with their evening meal, one afterwards to aid in digestion, and a glass before bed. Spirits were consumed at work and at social gatherings, even funerals. Outside of the home, women had little means of persuasion or control. Drinking was a social activity largely reserved for men and was often accompanied by visits to the local tavern, a space women were excluded from because drinking was not considered “proper womanly behavior.” In Baraboo, there were several saloons before there was even a bank. With their husbands abandoning temperance, and with no political recourse, a group of Baraboo women decided to strike back.

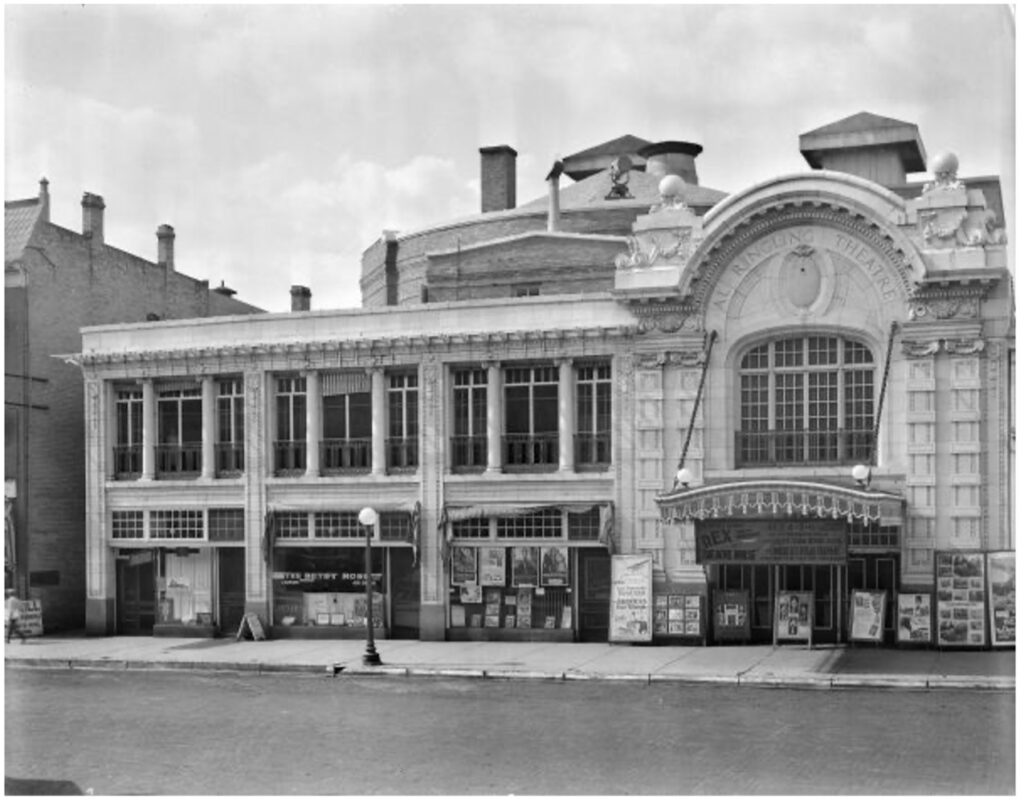

In 1854, a local who frequented the Brick Tavern inside the Wisconsin House—which is now the site of the Al Ringling Theater—drunkenly assaulted his wife and attempted to murder her. A group of local women beseeched the tavern’s owner, Michael Kormel, to stop serving the man, but he continued nonetheless. The man eventually died, leaving behind his wife and children. Fed-up and lacking any means to change the situation at hand, these women vowed to march on the Brick Tavern to destroy local spirits. One July morning, the women, accompanied by two pastors from the nearby Methodist and Congregational churches, arrived at the Wisconsin House. Shortly after arriving, they overthrew the casks of the Brick Tavern. Kormel was still asleep upstairs when his stock was dumped. The women continued, turning up the casks of another purveyor before reaching the tavern of Peter van Wendel. Uproar and commotion ensued, culminating with the reading of the riot act by a U.S. Marshall and the subsequent arrests of some of the women. This sequence of events became known as the Whiskey War of 1854.

The Wisconsin House (left) and Al Ringling Theatre (right). Before the theater was built, the Wisconsin House occupied the land. The Brick Tavern—located within the Wisconsin House—was the main target of the Baraboo Whiskey War, an event that would see its stock dumped. The Theatre was built in 1915 on the same site. Courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society ID # 29104 & 72938

In spite of the Wisconsin Temperance Movement’s early success in enacting legislation, alcohol remained pervasive in communities like Baraboo, especially as the movement was on the decline. In Baraboo, a growing German population and lack of a rail line ensured that alcohol stayed and was drunk by the community’s men. These conditions reflected the changing circumstances of many communities throughout the state. However, in Baraboo, a home-grown temperance movement ensured that these conditions were met with an explosion of temperance action not seen elsewhere in the state. This frustration materialized when a group of Baraboo women abandoned the era’s social norms by leaving their homes, entering a space deemed unproper to them and fit only for men, and destroying the intoxicates that attracted men to the site. The Whiskey War of 1854 was the result of a changing cultural landscape which left the Wisconsin temperance movement reeling and enabled a select group of Baraboo’s determined women to hold the line against the aggressive march of German influence and alcohol’s profitability.

Written by Austin Barrett, October 2022

SOURCES

Canfield, William H., and William H. Canfield. Outline Sketches of Sauk County: Including Its History, from the First Marks of Man’s Hand to 1861, and Its Topography, Both Written and Illustrated. Brookhaven Press, 2001.

Cole, Harry Ellsworth. A Standard History of Sauk County, Wisconsin. Brookhaven Press, 2003.

Dannenbaum, J. “The Origins of Temperance Activism and Militancy among American Women.” Journal of Social History, vol. 15, no. 2, 1981, pp. 235–252., https://doi.org/10.1353/jsh/15.2.235.

Dorsey, Bruce. Reforming Men and Women: Gender in the Antebellum City. Cornell University Press, 2006.

Dewel, Robert C. Sauk County and Baraboo: An Anecdotal and Chronological History: 1839 through 2008. Bob Dewel, 2009.

Earle, Alice Morse. Stage-Coach & Tavern Days. Dover Publications, 1969.

Mintz, Steven. Moralists and Modernizers: America’s Pre-Civil War Reformers. Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 2003.