Temperance was a defining and prominent movement in Wisconsin from the state’s admission to the union in 1848 until the mid 1850s. Temperance legislature, and the battles fought in favor of and against it, determined the state’s early legal trajectory.

Temperance arrived in Wisconsin with Yankees—migrants from the east coast—who came to the territory in the 1830s and 1840s. Specifically, Yankee Methodists, Congregationalists, and Presbyterians were noted for their abstinence from alcohol. While these migrants came from the homeland of America’s temperance movement, they settled within farming communities that were relatively unconcerned with the same principles. Before Wisconsin achieved statehood in 1848, the only law on the books pertaining to alcohol permitted liquor licensing and carried little language regarding punishment for those who sold unlicensed product. However, political developments after Wisconsin achieved statehood in 1848 ensured that a toothless law would not exist for long.

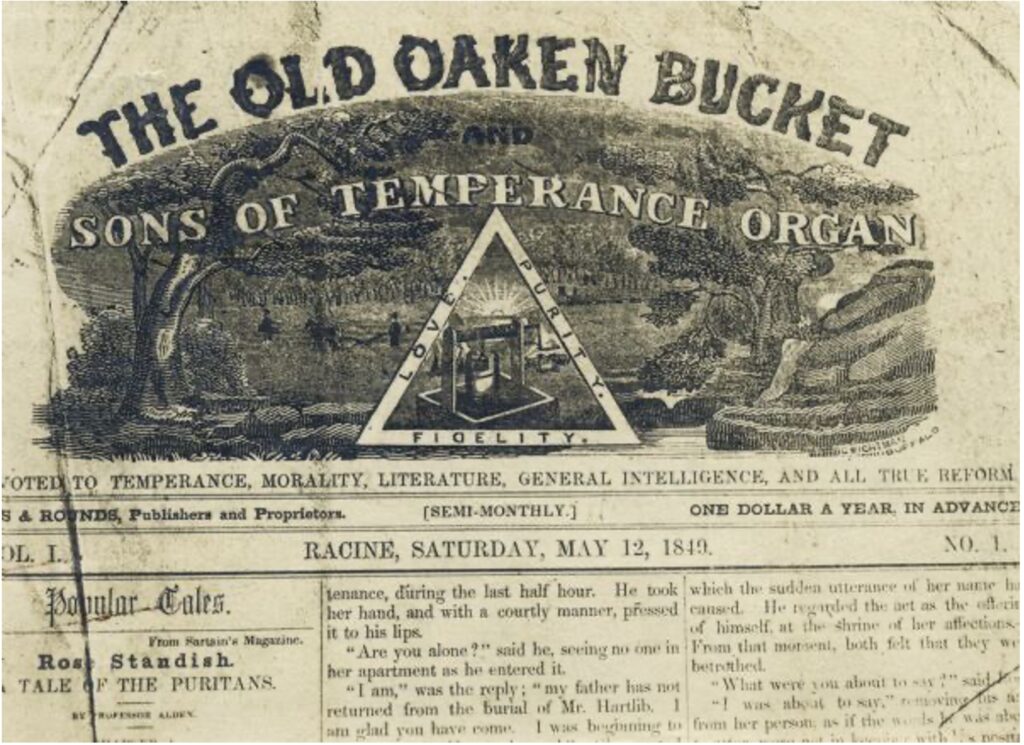

In 1848, the Sons of Temperance established a Grand Division in Milwaukee. The Sons of Temperance was a society founded on the east coast with a mission promoting a lifestyle abstinent from alcohol. Popular amongst Wisconsin’s pro-temperance Yankees, the division headed a number of already established local chapters, in addition to those that were to emerge. A senator from Milwaukee, John B. Smith, was named President. Not long after the Grand Division was established, temperance entered Wisconsin’s political realm via the agendas of anti-alcohol legislators like Smith who were aligned with the society.

During the state’s first legislative session in 1848, a bill was introduced by Madison Senator Simeon Mills that would repeal the licensing law with the goal of limiting and eventually eliminating alcohol consumption. The bill did not pass the Senate. However, in the year that followed, the Sons embedded themselves in Wisconsin’s state legislature, ensuring that temperance would be supported by powerful policy that went relatively unchallenged—if only temporarily. During a subsequent session in 1849, the Sons found success when a bill, sympathetic to their anti-alcohol worldview, was passed and replaced the previous law. While the new law did not abolish licensing, it required vendors to pay a $1,000 bond on which they could be sued for damages caused by customers consuming their liquor. Where its predecessor did little by way of punishment, the 1849 liquor law ensured that vendors faced potential harsh economic penalties. Viewed as a tentative achievement, Sons of Temperance member A. Constantine Barry remarked in his publication The Old Oaken Bucket, that this legal win was not guaranteed without public approval, of which this new piece of legislation had little. The law primarily found opposition amongst Wisconsin’s growing German population. Unlike Yankees, Germans loved their beer. For Germans, beer was socially and culturally important, and beer and the brewing process were central to communal life. Having recognized this, Barry later used his platform to advocate for an amendment to the 1849 law that he hoped would gain public support.

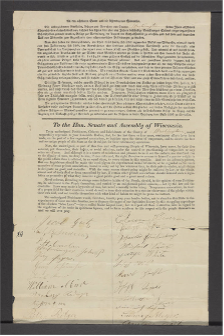

While the law was amended, it was not done in a way that garnered public support as per Barry’s suggestion. The amended 1849 liquor law abolished liquor licensing in the state of Wisconsin, much to the chagrin of the state’s German population. John B. Smith chaired a special committee that reported in favor of the new amended law. In honor of the chair, the law became known as the Smith Law. This development was met with public outrage which came to a head when a group of Germans—angered by the apparent affront to their social and cultural lifeways—marched on Smith’s Milwaukee home. Popular German sentiment of the time viewed the law as anti-democratic, with many arguing that an American ought to have the right to consume alcohol at their own discretion.

In the end, uproar about the Smith Law was pointless, as a lack of public support meant that the law was rarely enforced. By the end of 1850, the amended law was considered a loss that anti-alcohol legislators and the Sons sought and failed to correct. In 1851, a law was passed that returned Wisconsin to its licensing standard. The law was reminiscent of the unamended 1849 law but required a bond of only $500, half of the original required bond. The law’s passage was lamented by the Sons, including A. Constantine Barry who characterized the defeat in The Old Oaken Bucket as an abandonment of Wisconsin’s historical temperance pedigree.

Unfortunately for the Sons of Temperance and the Wisconsin Temperance movement at large, the 1851 defeat coincided with a continued rise in the beer-positive German population, particularly in eastern counties like Milwaukee. Perhaps most emblematic of this power shift was Smith’s failed reelection campaign and defeat at the hands of Dr. Franz Huebschmann. By 1855, nearly all efforts to introduce temperance policy were futile, and the Sons of Temperance effectively lost their political power. Pro-beer policy, courtesy of German legislators and supported by an established German public, supplanted the society’s influence, thus creating the conditions necessary for the ubiquitous German culture experienced throughout Wisconsin today. In 1848, temperance ruled Wisconsin’s state legislature, but by the end of the following decade, temperance as a political powerhouse had all but died out.

Written by Austin Barrett, October 2022

SOURCES

Draper, Lyman Copeland, and Reuben Gold Thwaites. Wisconsin Historical Collections. IX, State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1909, Page 428.

Ranney, Joseph A. “Demon Rum and Sunday Lager: The Temperance Movement in Wisconsin.” Wisconsin’s Legal History: An Article Series, Wisconsin Supreme Court, Madison, WI, 1998.

Schafer, Joseph. “Prohibition in Early Wisconsin.” The Wisconsin Magazine of History, vol. 8, no. 3, 1925, pp. 281–99. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4630552.

Shears, A. (2014). Local to National and Back Again: Beer, Wisconsin & Scale. In: Patterson, M., Hoalst-Pullen, N. (eds) The Geography of Beer. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7787-3_5

Rohrer, James R. “The Origins of the Temperance Movement: A Reinterpretation.” Journal of American Studies, vol. 24, no. 2, 1990, pp. 228–235., https://doi.org/10.1017/s0021875800029753.