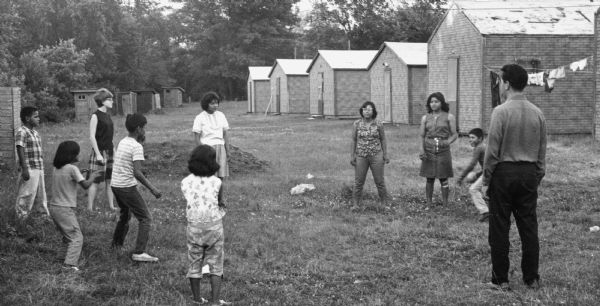

This cabin, once occupied by a family of migrant workers employed by the Bond Pickle Company, is located at the property of Thomas and Jamie Sobush of Pensaukee, Wisconsin. The cabin was originally one of many other small cabins, clustered together at the Bond Village Migrant Camp on Van Hecke Avenue in Oconto, Wisconsin.

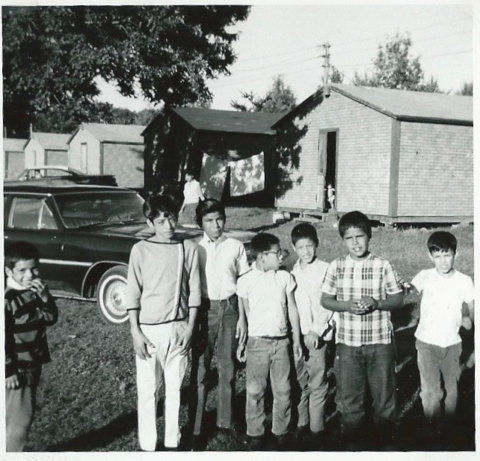

Cabins like this were home to seasonal migrant workers who came to Wisconsin to harvest cucumbers for the pickle industry. The cucumber harvest employed more migrant workers than any other Wisconsin crop. In the 1920s and 1930s, most of the migrant laborers who worked in the Wisconsin pickle fields were unmarried men. After World War II, however, migrant laborers in Wisconsin increasingly worked in family units, and by 1950 the majority of Wisconsin’s migrant workers were Latino. Following this shift toward family workers, pickle companies and farmers began to build small cabins so families could live together during the pickle harvest. Migrant workers in Wisconsin’s pickle fields were American citizens, and most of the workers came from Texas.

The family who occupied this cabin, the Saldañas, picked cucumbers for the Bond Pickle Company.

Amado P. Saldaña and his wife Teresa began coming to Oconto County to pick cucumbers in the 1930’s. For fifty years migrant workers like Amado, Teresa and their children lived in houses such as this at Bond Village. Each cabin measured a meager 24 feet by 14 feet. There were no internal room dividers. The walls were unfinished and uninsulated, and the floors were bare wood. Most of these cabins had a front door aligned so that if you continued walking forward you could walk straight to the back door. There was no indoor plumbing. A central bathhouse served the entire village. Although all of the cabins had some kind of electrical connection, the majority of the electricity was used by the two light-bulb outlets and the refrigerators found in every home. A few of the families were lucky enough to own a small electric floor fan, which was the only relief from the heat after long summer days working in the fields.

There was minimal furniture inside the homes; there wasn’t room. Because of the small dimensions of the space and depending on the size of the family, numerous family members slept directly on the floor with no mattress. Amado’s son, Antonio Saldaña, who spent his childhood working in the Bond cucumber fields, remembers that those unfortunate enough to sleep on the floor, would do so with a single blanket as a mattress and another blanket to cover themselves.

“Some were blessed to have a pillow and others were not,” he recalls.

Although the Bond Pickle Company no longer exists, several of these cabins have withstood the test of time. Collected artifacts and stories from the Saldaña’s cabin and the family that occupied it were displayed at the Neville Public Museum’s Estamos Aquí exhibit.

Written by Antonio Saldaña, September 2017.

SOURCES

Claras Backes, “The Migrants’ Union Comes to Pickle Country,” Chicago Tribune 20, 1968.

J.P. Kelly, “A timeline of Oconto’s pickle plant,” Green Bay Press-Gazette, 13 April 2017. https://www.greenbaypressgazette.com/story/news/local/oconto-county/2017/04/13/timeline-ocontos-pickle-plant/100432564/

Wisconsin Public Radio, “EPA Dismisses Scientists, What Drives Rural Economies, Green Bay’s ‘Estamos Aqui’ Exhibit,” Central Time, 8 May 2017. https://www.wpr.org/shows/central-time/epa-dismisses-scientists-what-drives-rural-economies-green-bays-estamos-aqui-exhibit

This object has been featured on WPR's Wisconsin Life!

Produced for Wisconsin Life by Erika Janik

What can this tiny migrant workers’ cabin tell us about the history of Wisconsin’s pickle industry?

Listen below to the segment on Wisconsin Public Radio’s Wisconsin Life:

Erika Janik:

Antonio Saldaña began working in the fields with his family as a migrant worker when he was four years old. He tells us about his childhood and becoming the first in his family to graduate high school and then college in Green Bay.

Antonio Saldaña:

I started working as a migrant worker at the age of four. Everybody had to work, not just mom and dad. Everybody, if you could walk and talk, you were expected to work. The family had been coming to Oconto since the ’30s and ’40s. We were just there from the middle of July until the first week, second week of September, and then the cucumber harvest would finish, and then you would go to the next state for harvesting another crop. You went to school there in each city that you were at, so you were never there more than 2/3/4, weeks. So you didn’t make a whole lot of friends because the language barrier. Because although we were born, like I was born in Oconto, we were only around the migrant workers so we could understand English and speak it, but it was very limited.

I was doing better academically, and the teachers took a, you know, an interest in what I had to say. So school was a lot of fun, but then a month before school was out, the students never understood why then I’d be gone, because then I would have to hop on the Greyhound, and you’re scared, you’re 14, so you get on the bus, and you’re on that bus for about two days, and then you travel all the way to Torrington, Wyoming, where you’re going to hoe beets. The sun was not our friend, he was our enemy. And I used to just look up at the sun and think, oh my gosh, I hate the sun. It is so hot, you know, but we loved the rain. If it rained, you didn’t have to work, but then there was nothing to do.

There was 14 of us. Our shack was only between 24 and 25 feet long, and about 14-16, feet wide. You know the joke, it’s so small I have to go outside to change my mind. That’s about the way it was.

Well, I always knew I didn’t know anything about education, because my dad had zero education, my mom only had a fifth grade education. But somehow, like in my mind, I knew this isn’t what I want to do, and there’s a way out, out of all the Saldañas and we’ve been here, I am a fourth generation, and I was the first one to graduate from high school.

You know, as a school teacher, I just tried telling my students, they go, this is this subject that I teach. Spanish might not seem important to you, but if you don’t like the situation that you’re in, education can do this for you. So that the kids want a lot of the kids have the same dreams that I had, but there’s a lot of the children that do that that are trying to get out. But how can you, how can you have dreams when you can’t even dream? When that son’s beating you? When there’s not enough to eat? How can you have dreams? We are not an invisible people. If you went back to the ’30s, ’40s, ’50s, ’60s and early ’70s, there was anywhere from 1,400 to 1,600 families at one time, in Oconto, in Neenah, all those places. We were a part of that economical system, and there’s nothing there to remember us.

Erika Janik:

Antonio Saldaña is a Spanish teacher in Green Bay, Wisconsin. Wisconsin Life is a co-production of Wisconsin Public Radio and Wisconsin Public Television, in partnership with the Wisconsin Humanities Council. Additional support comes from Lowell and Mary Peterson of Appleton. Find more Wisconsin Life on our website, wisconsinlife.org and on Facebook. I’m Erika Janik.