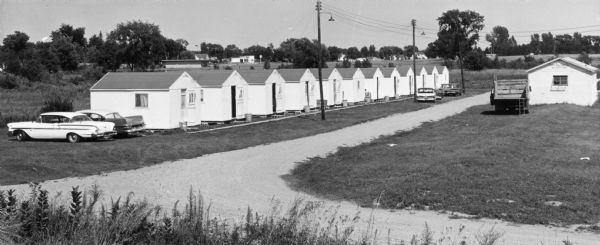

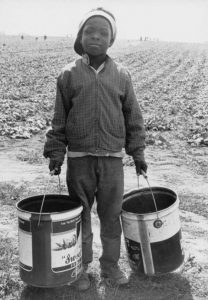

Before World War II, most of the migrant workers in Wisconsin’s pickle fields were single young men, and pickle companies provided housing for workers in large dormitories. After World War II, however, farmers began to hire more families to harvest pickles in the summer. With this transition, farmers and pickle companies began to build small single-family accommodations for workers.

The changing demographics of migrant labor in Wisconsin, from single men to families, drew the attention of state lawmakers. With more children working in the fields, for instance, lawmakers began to pass a series of child labor and school attendance laws. Meanwhile, beginning in 1949, Wisconsin began trying to provide protections for migrant worker housing needs. A special migrant camp law was passed first in 1951 and amended versions were passed in 1957 and again in 1961. The law applied to camps housing six or more migrant workers.

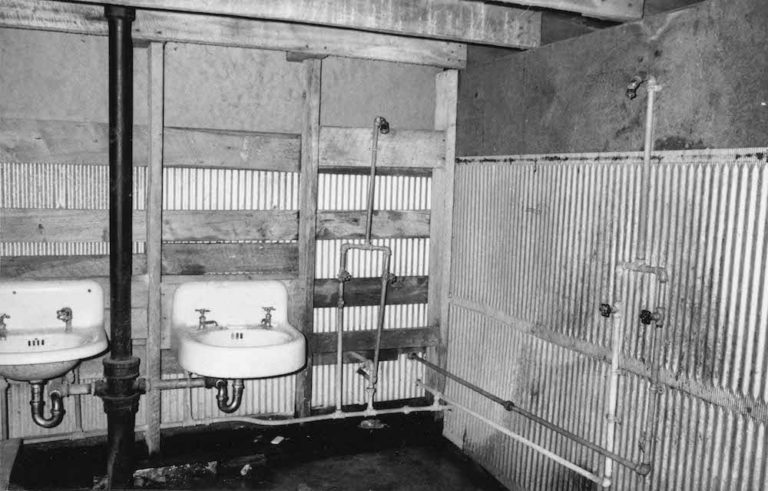

By 1961, the state’s migrant housing code set minimum standards for migrant worker housing in Wisconsin, establishing baselines for space per person, ventilation, toilet facilities, washing facilities, water supply, window screenings, door screening, waste disposal, etc. These standards included stipulations that required all migrant housing to be built within 200 feet of a toilet facility. All dwellings needed to have a window that could be opened and an electrical hook-up. Buildings like the migrant cabin occupied by the Saldaña family when they were picking cucumbers in Oconto County during the summer season were not required to include as much space as those intended for year-round occupancy.

Though the law set minimum standards, it was not consistently enforced. As the images on this page suggest, though the cabins were all built on similar patterns, some of them were well maintained while others were not. Sometimes overcrowding or inadequate facilities were an issue: sixteen people occupied the Saldaña’s cabin, for example, though state law required a minimum of 400 cubic feet of space per occupant over 12 years of age. David Giffey, a photographer who chronicled the experiences of migrant workers in Wisconsin, particularly highlighted the often-inadequate shower and bathroom facilities in migrant worker camps.

Wisconsin’s migrant housing laws were strengthened by support from President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty and the national housing reform bill of 1964. In the latter half of the decade, following federal guidelines, Wisconsin joined other Midwest states in adopting stronger and more consistently enforced minimum standards for migrant worker housing and housing inspections.

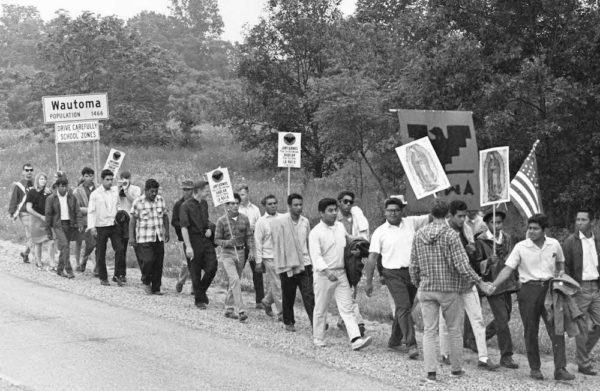

Changes in migrant worker’s labor rights also began to improve the quality of worker housing. During this period, the Delano Grape Strike and National Farm Worker’s Association inspired migrant laborers across the country to organize. In Wisconsin, Wautoma High School graduate Jesus Salas helped organize the Wisconsin farm workers’ union, Obreros Unidos. During this period, farm workers were not protected by the provisions of the National Labor Relations Act, and in Wisconsin they had only just won the right to unionize in 1964. In 1966, Salas and a group of farm workers marched from Wautoma to Madison to protest the living and working conditions for migrant workers in Wisconsin. Marchers demands included a minimum wage of $1.25, better housing conditions, better toilet facilities, and access to insurance. One year later, in 1967 they began a campaign to organize cucumber pickers working for Libby, McNeill & Libby, Inc., a large Chicago-based company that produced canned foods and beverages. After a decade of organizing, in 1977 the Obreros Unidos succeeded in passing the Migrant Labor Law, which guaranteed signed labor contracts, official start and end dates for contracts, and agreed-upon wages for workers.

Written by Antonio Saldaña, August 2017.

SOURCES

“United Workers March to Madison,” Wisconsin Historical Society image collection, Image ID: 90227.

Featured image: Central Wisconsin migrant labor camp cabins, 1967. Image courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society, Image ID: 91132.