Gay history in Wisconsin, while often focused on major cities like Madison and Milwaukee, was also being made in the often-overlooked rural parts of the state. One such place is the University of Wisconsin–Eau Claire, where a coalition of gay students founded their first gay student organization, the Gay Lesbian Organization (GLO), in 1984 to provide others on campus a safe place to meet and discuss their issues. Despite the fact that most other UW System schools already had similar organizations, the GLO was repeatedly denied a charter to become a registered student organization. In contrast to the strides being made on a state level, like the passage of Wisconsin’s landmark sexual anti-discrimination law, GLO had to work hard just to be allowed to meet on campus. Their struggle to educate their peers and gain acceptance at the university shows an alternative view for how gay people advocated for themselves during the 1980’s.

Creation of GLO probably would not have been possible without the passage of Wisconsin’s sexual anti-discrimination law in 1982. The law was the first of its kind in the nation to protect LGBT people from discrimination in employment and housing. After being introduced in several legislative sessions, the bill gained bipartisan and religious support in the state senate and was signed into law under republican governor Lee Dreyfus. For many gay UW–Eau Claire students, seeing this kind of support emboldened them to live more openly even though there was not much support for them in the area. It also reduced some of the barriers that came with starting a student organization, like the problem of having to publicly list officers. Though it was still difficult to convince people to put their involvement in the club on record, there was no longer a threat that students would be kicked out of their dorms or fired for being associated with such an organization.

Without a group charter, the GLO was unable to book space to meet on campus, so members instead were forced to form their club in students’ homes. This was a problem because many of them either lived in the dorms or with their parents, which meant spaces where people would not have to expose their sexualities were in short supply. They quickly began forming an organizational structure for the club, which included the election of co-presidents so that gay men and gay women would have equal leadership roles. Lack of representation of other members of the LGBT community was unintentional and would go on to be solved by later iterations of the group, but this original organization reflected the identities of the GLO’s founders and early recruits. This lack of awareness of other LGBT students not only demonstrates the necessity of this group, but also reflects the way that members met: they were introduced by a mental health counselor who had been helping them with issues related to their sexuality.

Being one of the last schools in the UW System to create a gay organization gave members hope that their charter would be quickly adopted. Co-founder Edward Frank even visited UW–Stout in nearby Menomonie to get an idea for how their gay club operated. After only a few months, on March 23rd, 1984, the club would submit its first application to the Student Senate for their charter. Expecting scrutiny, the GLO took measures to avoid denial of their application on some technicality including copying the majority of their constitution and by-laws from another already approved student organization. Within three days the club received a letter denying their application, seemingly without any directions on how to improve their constitution for resubmission. At this point they faced the challenge of convincing a faculty member to be their advisor. Unmarried professors refused the role for fear of being perceived as gay, and professors who were not yet fully established did not want to risk being alienated from their peers. Eventually they found Dr. Elliot Garb, an older, married professor who was willing to be their advisor; with this ally on their side they were given provisional organization status as their application was reviewed.

Less than a month after their first attempt, the club resubmitted their application and was rejected again. This time the Student Senate issued a letter detailing eight mistakes they would have to fix to be accepted, including addressing the semi-exclusive nature of a club for gay people. Then, as now, student organizations in Wisconsin must, at least in theory, be open to all members of the university who meet the requirements for the organization regardless of factors like race, ethnicity, sex, and sexuality. This meant the constitution had to be written in a way which would allow straight students to attend meetings, while simultaneously balancing the need for its members’ privacy. Even though other clubs on campus, like those that were ethnicity based, faced similar discrimination concerns the Student Senate would go on to cite this as a reason for rejecting the organization a second time.

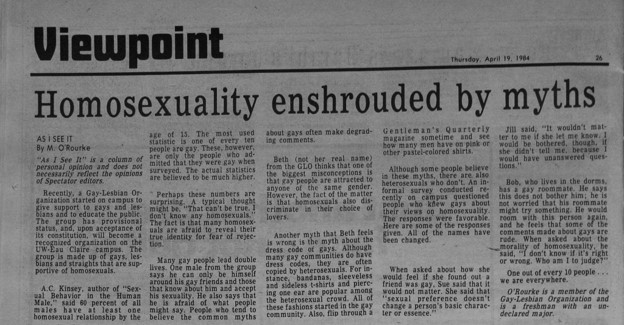

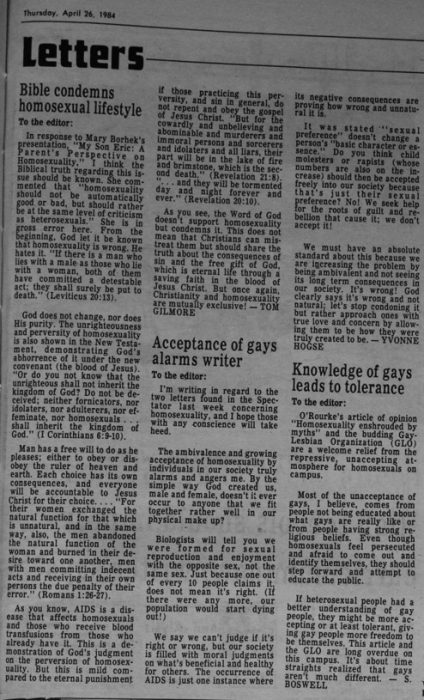

While the issues the Student Senate had may have been valid, this second rejection made the group feel disheartened. They rightly noted that many of the problems cited had not also prohibited the organization whose constitution they had modeled their own from being granted their charter. Though none of the GLO’s founders had initially intended to be activists, one of them, Jill Muenich, began researching discrimination to build a case against the Student Senate to bring to their faculty adviser Dr. Elliot Garb. At the same time, the club had their constitution reviewed by a lawyer to make sure it did not violate any anti-discrimination laws. Articles were written in the school paper to make a case that gay people were just like anybody else and deserved their own space. This struggle went on back and forth until finally the faculty adviser was able to convince the Student Senate to let them through.

While this kind of discrimination was unlike UW–Madison’s Gay Purge of 1962, it was no less frustrating or energizing for the students at UW–Eau Claire. The major difference was that the discriminating body was not the university, but other students. Many of these students did not know any gay people, nor did they have knowledge of the issues which plagued gay students. As a few members of GLO have mentioned in oral history interviews, even public libraries in the Eau Claire area were lacking in resources about the LGBT community; and those that had books, usually restricted access to them. There was a fundamental lack of accessible knowledge about queer people even as AIDS began to tear apart gay communities in places like Milwaukee and Minneapolis in the 1980s. Though AIDS activism would not become a large component of GLO, members of the club did informational sessions during classes to educate their peers about gay issues and people.

Listen to co-founder Jill Muenich explain to interviewer Melissa Schultz the group’s struggle to become chartered.

GLO at UW–Eau Claire exemplifies the way gay people rise to meet the needs of their community when faced with adversity. By this time, other organizations around the state had already begun providing spaces for gay people to meet, talk, and had even moved into more deliberate political action, like those formed in response to the AIDS epidemic. Though the GLO at Eau Claire faced prejudice from their peers, the students used that to gain momentum and rally their community; letting people know that they were there to stay.

Written by Rae Kalscheuer, October 2023.

Sources

GLO pin, University Historical Collection 351, Box 1, Folder 6, The University of Wisconsin–Eau Claire Gay and Lesbian Oral History Project, 2013-2014, Special Collections & Archives, McIntyre Library, University of Wisconsin–Eau Claire, Eau Claire, Wisconsin.

Johnson, Carla, interview by Melissa Schultz, November 22, 2013. University Historical Collection 351, Box 1, Folder 6, The University of Wisconsin–Eau Claire Gay and Lesbian Oral History Project, 2013-2014, Special Collections & Archives, McIntyre Library, University of Wisconsin–Eau Claire, Eau Claire, Wisconsin.

“Letters to the Editor,” The Spectator, University of Wisconsin–Eau Claire, April 19, 1984, 27.

Muensch, Jill, interview by Melissa Schultz, November 30, 2013. University Historical Collection 351, Box 1, Folder 6, The University of Wisconsin–Eau Claire Gay and Lesbian Oral History Project, 2013-2014, Special Collections & Archives, McIntyre Library, University of Wisconsin–Eau Claire, Eau Claire, Wisconsin.

O’Rourke, M., “Homosexuality enshrouded by myths,” editorial. The Spectator, University of Wisconsin–Eau Claire, April 19, 1984, 26.

PBS Wisconsin, Wisconsin Pride. “Part 2: Struggles and Victories,” aired June 2023. https://pbswisconsin.org/webisode/wisconsin-pride/part-two-struggles-and-victories/video/

Red pin, 1985, University Historical Collection 351, Box 1, Folder 6, The University of Wisconsin–Eau Claire Gay and Lesbian Oral History Project, 2013-2014, Special Collections & Archives, McIntyre Library, University of Wisconsin–Eau Claire, Eau Claire, WI.

Schultz, Melissa. “If Sexual Orientation Is a Choice, When Did You Choose?: A History of the LGB Student Group at the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire, 1983-2000.” MA Thesis, The University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire, 2017.

RELATED STORIES

OBJECT HISTORY: 602 Club T-Shirt