Gay students at the University of Wisconsin-Madison have not always received the protection they do today; in fact, from 1962-1963 the university attempted to systematically identify and expel gay students. The Dean of Men, in collaboration with Student Health Services and the Department of Protection and Security, created a list of suspected homosexuals who were subsequently tracked down and interrogated. Students were encouraged to give up the names of fellow gay students to avoid being expelled. Though gay students had previously been targeted, the intensity of these Lavender Scare tactics affected them in ways those attempts at enforcing heterosexuality on campus had not before. The Gay Purge of 1962-1963 is a story which touches on university politics, national witch-hunt campaigns, and international fear all coming together to affect students who were simply trying to live their lives.

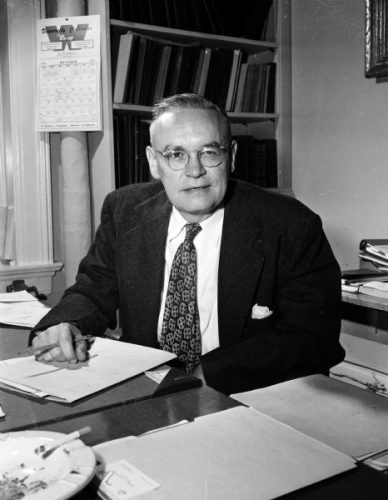

The driving force behind the purge was Dean of Men Theodore Zillman, whose job was to oversee and control the behavior of male students. In this period, Zillman alongside many other university staff became increasingly concerned about student conduct as it related to “sexual deviancy,” a vague term which included everything from gay men, to voyeurs (Peeping Toms), to men who went to parties with unchaperoned women.[1] Many of these problems stemmed from the fact that gender segregation, which had been the norm, was no longer possible. For years the university had been over-admitting students, causing a housing crisis for young women who had to adhere to strict guidelines about where they could live off-campus. Single women had to choose from special university-approved apartment buildings that both did not allow male tenants and which hired a chaperone to enforce curfews and forbid men from entering. In 1959, the University ended most chaperoning requirements on the stipulation that students were now liable if they were to “‘endanger the moral integrity of another” or damage the “good name of the university”.[2] Once male-female conduct rules had loosened, the moral panic over sexuality concerning sex shifted largely onto gay men.

Part of the urgency for stopping “deviant” behavior stems from UW-Madison’s position as a public university just a short walk from the State Capitol. Zillman’s repressive attitude can be seen as a means for mitigating the financial risk to the university posed by rowdy college-aged men whose actions were witnessed by the legislators at the other end of State Street. Hiding and removing the problem of sexual deviancy became a priority; in fact, historian Richard Wagner speculated, “The purge was hidden from view because administrators did not want the public or state government to know that a large number of homosexuals attended the university.”[3] Similarly, Zillman also worried about parents whom he believed would not continue sending their children to the university unless they felt it was a safe environment. For years the university adopted a system of in loco parentis (‘in the place of the parent’), to govern students as if they still lived with their parents. Unfortunately, prejudices and misconceptions about gay men at the time intersected with Zillman’s wishes to exert control on a rapidly changing student body demanding more and more freedom.

Though no longer the case, at this time homosexuality was classified as a mental illness, and one of the most wide-spread fears was that those afflicted were trying to recruit straight people. Since the late 1940s at the university, psychiatrists at Student Health Services like Dr. Annette Washburne worked to classify homosexuals and to find treatments for homosexuality. Washburne believed engaging in homosexual behavior did not make someone a homosexual, but in her estimation, most of the people who engaged in that behavior were just experimenting and could be convinced to stop if they were willing to go through conversion therapy. There were only a few “true homosexuals” determined to continue their behavior and who needed to recruit others to do it with them.[4] During the Purge, over a decade later, administrators agreed their primary concern was eliminating homosexual behavior rather than expelling homosexuals students, evidenced by their offering leniency to those who gave up names and who sought counseling.

The Lavender Scare of the early-to-mid-1950s, a federal campaign against homosexuals working in areas of national security perpetrated by Wisconsin’s own Senator Joseph McCarthy, also contributed to the public’s distrust and hatred of gay people. McCarthy publicly speculated that the Communists would be able to blackmail gay Americans into committing treason. Though Senator McCarthy never had a large base of support at the university, and by the time the Purge began his national influence had waned significantly, his tactics of making a list and intimidating suspected homosexuals were the main tactics adopted by the university. It is likely that renewed fears about homosexuals in government prompted by a 1961 gay British spy scandal involving Soviet blackmail, and popular media like the 1962 movie Advise and Consent (which depicted a gay man being blackmailed for his sexuality), were factors that led administrators to believe homosexuality was becoming an urgent problem–despite there being no significant change on campus. In their eyes, having a degree from UW-Madison meant that the university was attesting not only to academic but also moral integrity, and because they believed homosexual behavior was both immoral and dangerous, these students were damaging the good name of the university.

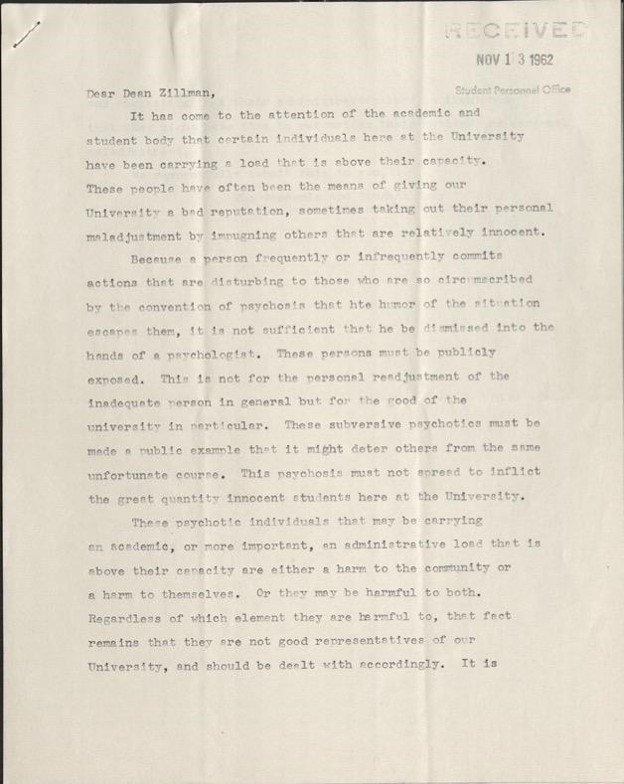

While it’s difficult if not impossible to understand the extent of the Purge’s effects, the way it was conducted is much more clear. An emphasis on staying closeted at the time it was occurring, student conduct records which remain heavily restricted to this day, and intentional misdirection on the part of administrators when doling out disciplinary actions to students means it will probably never be known exactly how many students were affected by this campaign. However, the testimony of a few of the gay students from the time and the apparatus which Dean Zillman created tells a compelling story of discrimination. For instance, before Dean Zillman even broached the idea of a gay purge with the rest of the Student Life and Interests Committee he encouraged making a deal with the Dane County District Attorney to offer legal immunity to students who would give up the names of other gay students.

The first thing the Dean’s office did was create a list of suspected homosexuals filled with as much information on the students as possible. Dozens of names were listed each with an associated file that contained a history of the students’ residences, their phone numbers, workplaces, alleged sexual partners and more. Though the Dean’s office could have verified some of this information, like addresses, easily enough, even these facts were sometimes the result of hearsay and rumors. One student who was questioned by the Dean asserted that “almost everything in the report was inaccurate to some degree or another,” including listing people he barely knew as his partners and showing him living somewhere that he did not.[5] Despite the errors, these files had an intimidating effect on many gay students at the time causing them to feel like they had to either repress their behavior or leave.

As Dean Zillman called in more and more students, fear grew amongst a small, secretive community of gay men. For some, it no longer felt safe to go out to the popular gay bars of the time, such as the 602 Club and Kollege Klub, because they might be next for persecution. Even hanging around gay men who displayed what were construed as more stereotypical attributes or following gay fashion trends like bleaching their hair threatened their safety because one’s associations became all it took to be listed as a suspected homosexual. One gay student, Lewis Bosworth, was lucky enough to be warned about the purge by a friend who spoke to him in French in case anyone was listening in on their conversation.[6] Even opting out of helping the Dean of Men on his crusade sometimes had disastrous consequences; Bosworth lost a scholarship because he refused to assist in the investigation. Another student recounted finding his gay roommate after he had “slashed his wrists” because he was so scared of being outed.[7] Other students simply left campus, either to await the end to the Purge or never to return to the university.

The end of the Purge came just as quickly as it had begun. Counselors at SHS had to beg the administration to call off their efforts citing the stress it was causing their patients. Additionally, over the course of the investigation the committee had begun to uncover secrets about the sex lives of respected faculty members and staff. Unlike the undergraduates and graduate students whose options were limited in terms of fighting off the administration, these professors would be much harder to get rid of. Though Wisconsin’s anti-discrimination law would not go into effect until 1982, the Gay Purge of 1962-1963 was the last time the University of Wisconsin – Madison would systematically discriminate against gays for their private and consensual sexual relations

Written by Rae Kalscheuer, October 2023.

Footnotes

[1] Curti, Merle. The University of Wisconsin: A History, Vol. 4, Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1999.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Wagner, Richard. We’ve Been Here All Along: Wisconsin’s Early Gay History. Madison: The Wisconsin State Historical Society, 2019.

[4] Gerard, Ezra. “Gay Purge: The Persecution of Homosexual Students at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, 1962–1963.” Public History Project. Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System , March 22, 2021. https://publichistoryproject.wisc.edu/gay-purge-persecution/.

[5] McCrea, Ron. “Madison Gay Purge.” Midwest Gay Academic Journal Vol 1, iss. 3 (1978).

[6] Bosworth, Lewis, Oral History Interview by Scott Seyforth, UW-Madison Oral History Program (04-07-2009): http://digital.library.wisc.edu/1793/57107

[7] McCrea, “Madison Gay Purge.”