The Decline of Wheat

From 1840 to 1880, Wisconsin produced about one-sixth of the nation’s wheat. But soil depletion, insect infestations, plant disease and competition from other states lowered Wisconsin yields and eroded profits. By 1880, wheat supremacy had passed westward to Minnesota and the Dakotas. Wisconsin farmers desperately sought a profitable substitute for wheat.

A Chicken-and-Egg Problem

Progressive farmers in Wisconsin noted the success of dairying in the similar climate of New York State and aimed to duplicate that success in the Badger state. The Wisconsin Dairymen’s Association, formed in 1872, led this effort. Their task was a formidable, chicken-and-egg problem: convincing farmers to switch to dairying without an established demand from creameries and cheese factories, and convincing dairy producers to set up shop where there was no reliable milk supply.

A Market Revolution

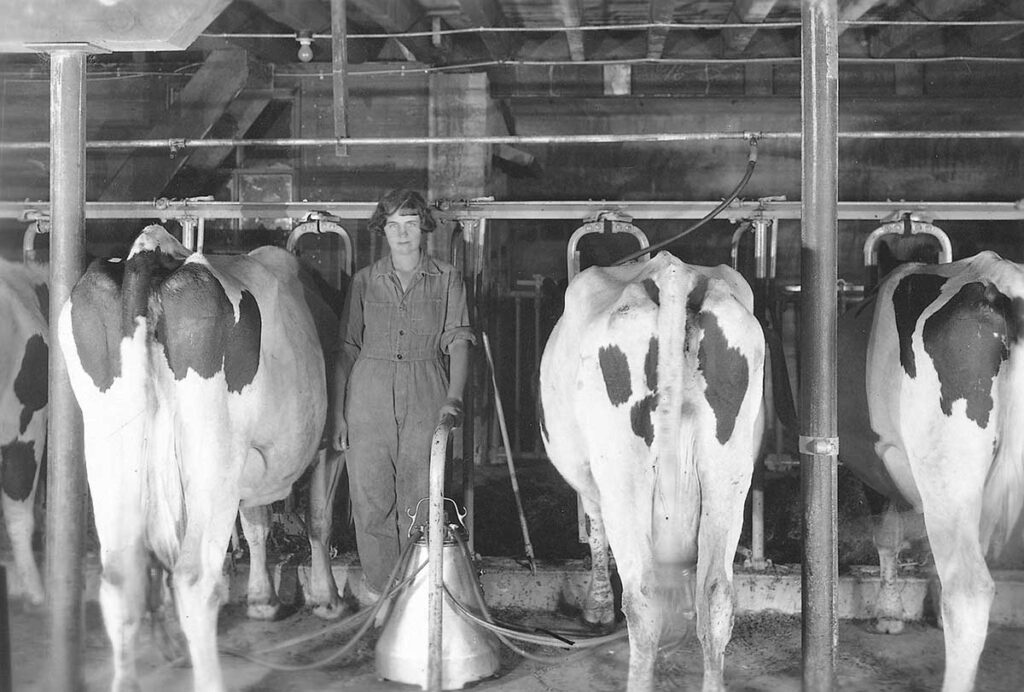

To transform Wisconsin’s agricultural economy, farmers had to fundamentally revise their practices and work routines and adopt new technologies like silos and Babcock testers. At the same time, cheese making, which had been a seasonal, farmstead activity, had to be professionalized and expanded. In order to support so many dairy farms, Wisconsin cheese had to become competitive on national and international markets, which in turn required strict quality control, efficient and affordable transportation, good promotion, and favorable legislation.

A Pivotal Invention

The Babcock test was crucial in this process. Dairies used it to reduce skimming or watering down milk and to pay the best farmers more for their efforts. Farmers used it to identify their most productive cows and to improve their herds. Butter and cheese makers used it to learn how efficient their manufacturing processes were. After 40 years of promoting feed research, herd testing and improvement, new technology, inspection for quality, and other best practices, the Wisconsin Dairyman’s Association and other promoters could claim success. By 1915, Wisconsin had become the leading dairy state in the nation, producing more butter and cheese than any other state.

Written by David Driscoll, December 2013.

SOURCES

Eric E. Lampard, The Rise of the Dairy Industry in Wisconsin: A Study in Agricultural Change 1820-1920. Madison; State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1963.

Wisconsin Historical Society, “Turning Points: The Rise of Dairy Farming.” https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/turningpoints/tp-028/

RELATED STORIES

The Men Behind the Butterfat Test

The Babcock Tester and the Wisconsin Idea

How Does a Babcock Tester Work?

OBJECT HISTORY: Babcock Butterfat Tester