Simplicity, Simplicity, Simplicity

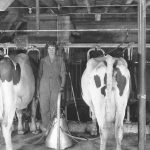

In 1890, few farmers had ever taken a science class, and even if they understood the potential benefit, most lacked the cash to pay an expert for laboratory testing. Babcock’s great accomplishment was to develop a powerful, reliable test that was simple enough and cheap enough for average farmers and cash-strapped small dairies to adopt.

How It Works

The basic test involves just a few steps:

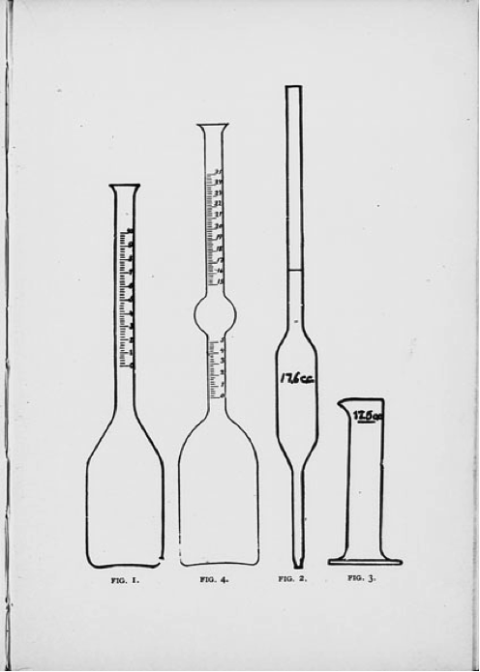

1. Using a pipette, measure 17.6 cubic centimeters (cc) of milk into a specially made, thin necked flask.

2. Add 17.5 cc of sulphuric acid to the test flask and gently swirl the acid and milk together. The acid dissolves the casein, or proteins, in the milk, freeing the fat globules from the liquid.

3. Spin the flasks in “whirler,” or centrifuge, for 5 minutes, rotating at 700 to 1200 rpm. Centrifugal force pulls the heavier portion of the mix to the bottom of the flask and forces the lighter portion – the butterfat – towards the top.

4. Add hot water to the 7% mark on the neck and spin for another minute. This helps the fat stay fluid and float up into the neck. If necessary, place the flasks in hot water before measuring, again, so that the butterfat can flow into the neck easily.

5. Read the height of fat column in the neck of the flask, subtracting the lower reading from the upper. The flask is marked in butterfat percentage, rather than in cubic centimeters, so no further calculations are needed.

Slightly different flasks and procedures were used for measuring cream, skim milk, or whey, but the basic concept was the same.

As in any test, accuracy depended upon care and consistency – in the uniformity of the milk sample, in measuring liquids, in the strength of the acid, in whirling speed and duration – but the test was robust enough and forgiving enough that it could be used effectively with minimal training and expense.

Want to learn more about the Babcock Butterfat Tester? Watch this video from Professor Emeritus David L. Nelson (Biochemistry, University of Wisconsin-Madison).

Written by David Driscoll.

SOURCE

Babcock, S.M. “Directions for using the Babcock milk test and the lactometer,” in Bulletin of the University of Wisconsin Experiment Station, no. 36 (July 1893).

RELATED STORIES

Becoming the Dairy State

The Men Behind the Butterfat Test

The Babcock Tester and the Wisconsin Idea

OBJECT HISTORY: Babcock Butterfat Tester