Oak Trees have been regarded for centuries as a symbol of strength, moral, and knowledge, and throughout history have been represented in different mythologies to show these attributes. And for the original Council Oak Tree, grown in Eau Claire, it also held the same esteem, being of key importance historically for the University of Wisconsin school, as well as culturally, as legends that have grown with the tree claim to describe its significance to indigenous tribes and nations in the Chippewa Valley. While there is no history documented of the original Council Oak Tree, deductive reasoning by tribes within the area, as well as History department faculty on the campus have been able to decipher some truth within the supposed legends.

Following the introduction of The Eau Claire Normal School in 1916, the original Council Oak Tree, which dates to the early 1800’s, became positioned in an area between academic buildings on campus. With the founding of the school, there was an attempt to blend cultures of the indigenous tribes of the area for the attending students. First documented in 1923, Eau Claire Normal School adopted the Camp Fire movement, in which students, primarily women, would adopt pseudo-Indian names for themselves, dressed as Native Americans, and preformed “ceremonial dances” at their meetings.

Stories about the supposed significance of the Council Oak Tree for the local indigenous tribes of the area are first documented in the early 1930’s. First written by the Eau Claire State Normal School’s newspaper and yearbook documenter Periscope, discussion of the tree’s significance came at a moment when the school wished to begin to create and document a rich historical identity to help compete with surrounding schools.

In 1938, the Periscope provided an essay on the “historical background of Little Niagara Creek”, a small stream running between academic buildings. The article said that “without a doubt” the entrance of Little Niagara into the Chippewa River was the boundary between Ojibwe and Sioux territory delineated by the Treaty of Prairie du Chien in 1825. The yearbook wanted this event to be recognized as “one of the traditions of the college”, and thus Little Niagara Creek, as well as a tree near the mouth of Little Niagara that would come to be known as the Council Oak Tree, would play an important role of the college to develop its identity in the 1930’s.

According to the claims, the original Council Oak Tree marked a spot of meeting for the Ojibwe and Dakota tribal leaders, where they negotiated treaties, used its large branches for shelter, and more generally provided a gathering place for multiple generations of their people over the 19th century. The Ho-Chunk, Menominee, and Potawatomi nations were also cited to have used it as a place to share knowledge and discuss peaceful resolutions.

In 2009, UW – Eau Claire emeritus professor Richard St. Germaine, a member of the Lac Courte Oreilles Tribe of Ojibwe, located 100 miles north of Eau Claire, offered his own interpretation of the tree’s significance. During his undergraduate studies at UW – Eau Claire, St. Germaine began to hear stories about the legends of the tree being where a multitude of councils were held under the large branches. St. Germaine believes that the likely age of the tree, in combination with stories of when these councils supposedly took place, made it unlikely that the tree would have been large enough to shelter gatherings or serve as a landmark.

However, citing topographical knowledge and his cultures history, St. Germaine believes the story of the Council Oak Tree might not be entirely false. In an interview in 2009 St. Germaine detailed, “I think Little Niagara is a very prominent feature along the river and I think it’s likely that the Ojibwa and the Santee chose Little Niagara for that reason. I would see them parking their canoes here by Little Niagara drinking their water and then walking upstream a ways and then finding an opening. . . I would have no proof, but knowing the, knowing the Indian mind they would look for things like Little Niagara.”

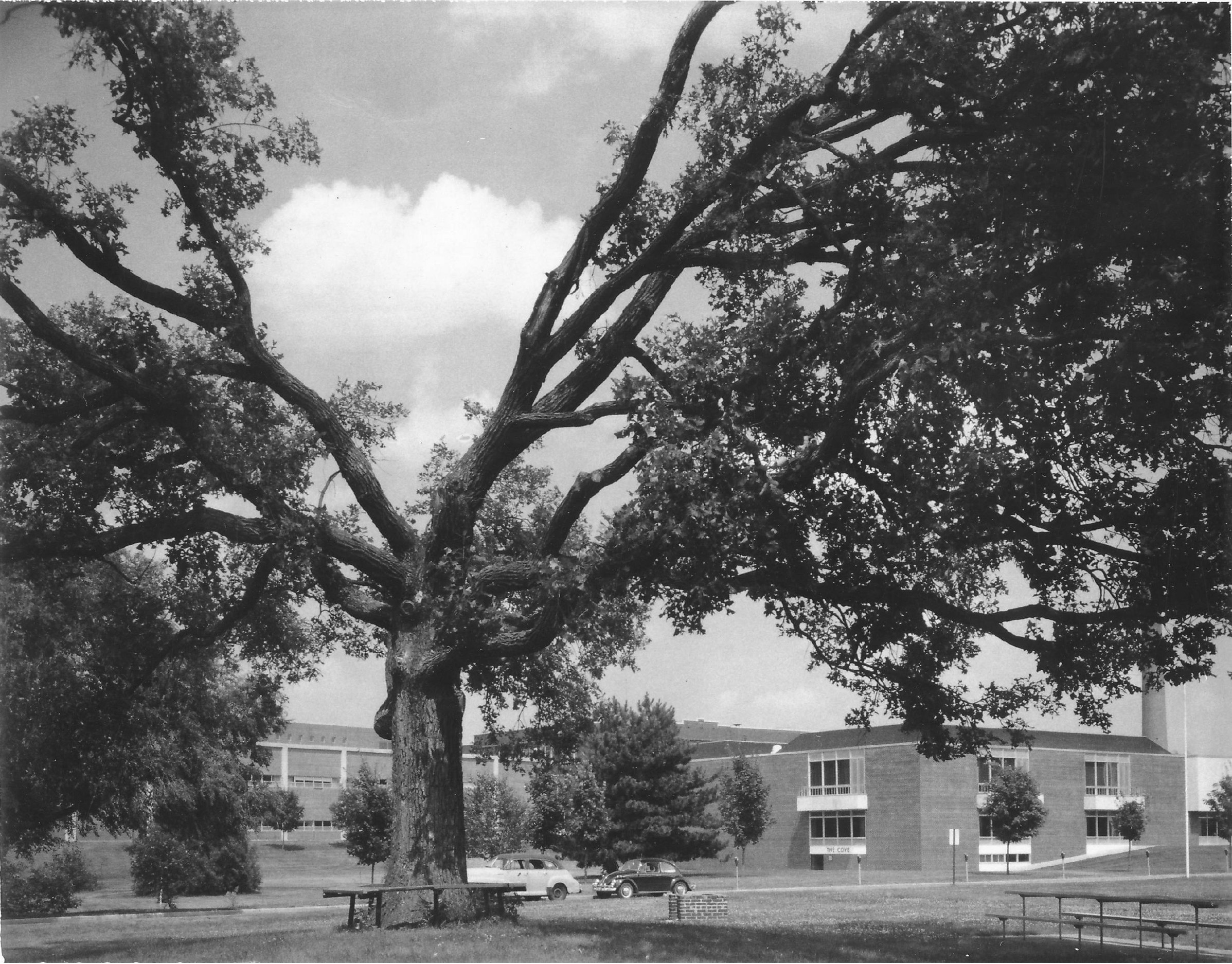

On the evening of July 10, 1966, a summer storm blew through the city and lightning struck the center of the tree, destroying major integral branches. The storm left a large gap in the center of the tree and ruined its otherwise perfect shape. Yet, the Council Oak continued to stand strong for over 20 more years, until the remaining portion of the tree fell to a windstorm in 1987.

A replacement Council Oak Tree was planted during Earth Day ceremonies in April of 1990, being buried in the same spot of its predecessor. Ernie St. Germaine, elder of the Lac du Flambeau tribe, tied ribbons into the tree’s branches, each representing the four directions and the heavens, with the University making a promise on that day that this new Council Oak Tree would stand for at least 300 years, and continue the legacy of cultural and historic significance for generations to come.

While no one may ever know how accurate the legends of the original Council Oak Tree are for cultural and historical heritage to indigenous tribes and nations of the area, there is agreement amongst scholars and tribal elders that the legends are based in some historical truth. The University school has adopted the stories and have thus made the original Council Oak a key addition to their school and campus. They have done this is a multitude of ways, such as, having the tree adorned on their university seal; naming conference rooms and ballrooms within their student center after the tree and the local tribes of the area that were said to have met under it; and perhaps the most important, by centering their campus academic and residence buildings around the spot of the original tree where the new Council Oak is planted.

Written by Bailey Carruthers, October 2021.

SOURCES

Robert J. Gough and James W. Oberly, “Historic Council Oak,” Building Excellence: University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire, 1916-2016. (Online Exhibit for McIntyre Library, University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire). Archived. http://web.archive.org/web/20060505021114/http://www.uwec.edu/Library/archives/exhibits/oak.htm