Famed for its healing properties, the mineral spring water of Waukesha, Wisconsin grew widely popular during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The Waukesha Springs Era (1868-1914) saw the rise of over 200 spring water companies and a robust resort culture. In this small Wisconsin town, a lavish Victorian culture and tourism industry flourished alongside the commercial success of the spring water businesses. The period was influenced by developments in medical treatments, the rising wealth and expanding middle class of the Gilded Age, and advancements in railroad transportation.

People travelled from far and wide wanting a taste of Waukesha’s healing waters. At the height of the Springs Era, Waukesha received thousands of visitors each year, turning the tiny prairie town into one of the premier vacation spots of the Midwest. At the time, medicinal mineral springs were discovered in different places across the United States, from New York to Colorado, creating regional destinations for medical tourism. Although not the only mineral springs hotspot in the Midwest, Waukesha was the largest, home to over fifty mineral springs throughout the county. Located near Milwaukee and Chicago, Waukesha was also just a train ride away for city dwellers. To accommodate the influx of tourists to Waukesha, proprietors built new hotels, parks, and entertainment venues alongside the springs. Before long, Waukesha became known as “The Saratoga of the West,” nicknamed after the resort town in New York, and quickly became a place for the wealthy to spend their summers. Waukesha’s reputation drew notable high society visitors, including Mary Todd Lincoln, who visited Waukesha in search of rest and healing after the assassination of her husband, President Abraham Lincoln.

The natural springs of Waukesha were rich with minerals used to heal a wide range of illnesses, from indigestion to kidney disease, during the Victorian Age. Decades before the discovery and introduction of antibiotics, doctors treated diseases with mineral disinfectants. Spring water contained natural minerals, such as sulphur and charcoal, which were believed to have curative properties. The discovery and promotion of Waukesha springs, replete with precious mineral disinfectants, drew droves of visitors to Wisconsin to taste the healing waters.

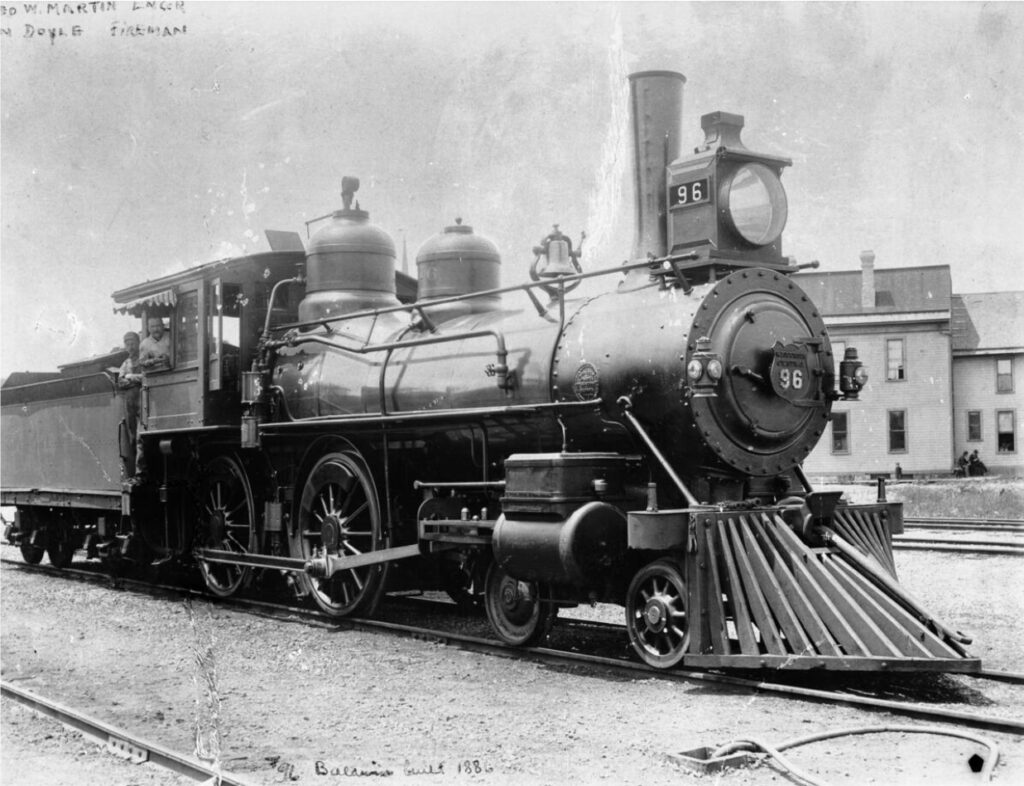

Meanwhile, the Industrial Revolution brought a new era of enterprise and innovation to American cities. The development of factories opened new opportunities for managerial and clerical work, which allowed men and women to take up office jobs and fostered the growth of the American middle class. People found new ways to spend their income on consumer goods and leisure activities. Meanwhile, inventions like the trolley, railroad, and eventually the automobile made transportation much easier, so people could travel from city to city more quickly. In Waukesha, three train lines – the Chicago and Northwestern; the Chicago, Milwaukee, and St. Paul; and the Soo Line – ran directly from Chicago, carrying visitors from the major city to the Wisconsin resort town. Many Chicago families spent their summers and weekends in Waukesha, which became a tourist destination with the growing popularity of its famous mineral spring waters.

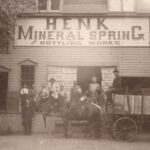

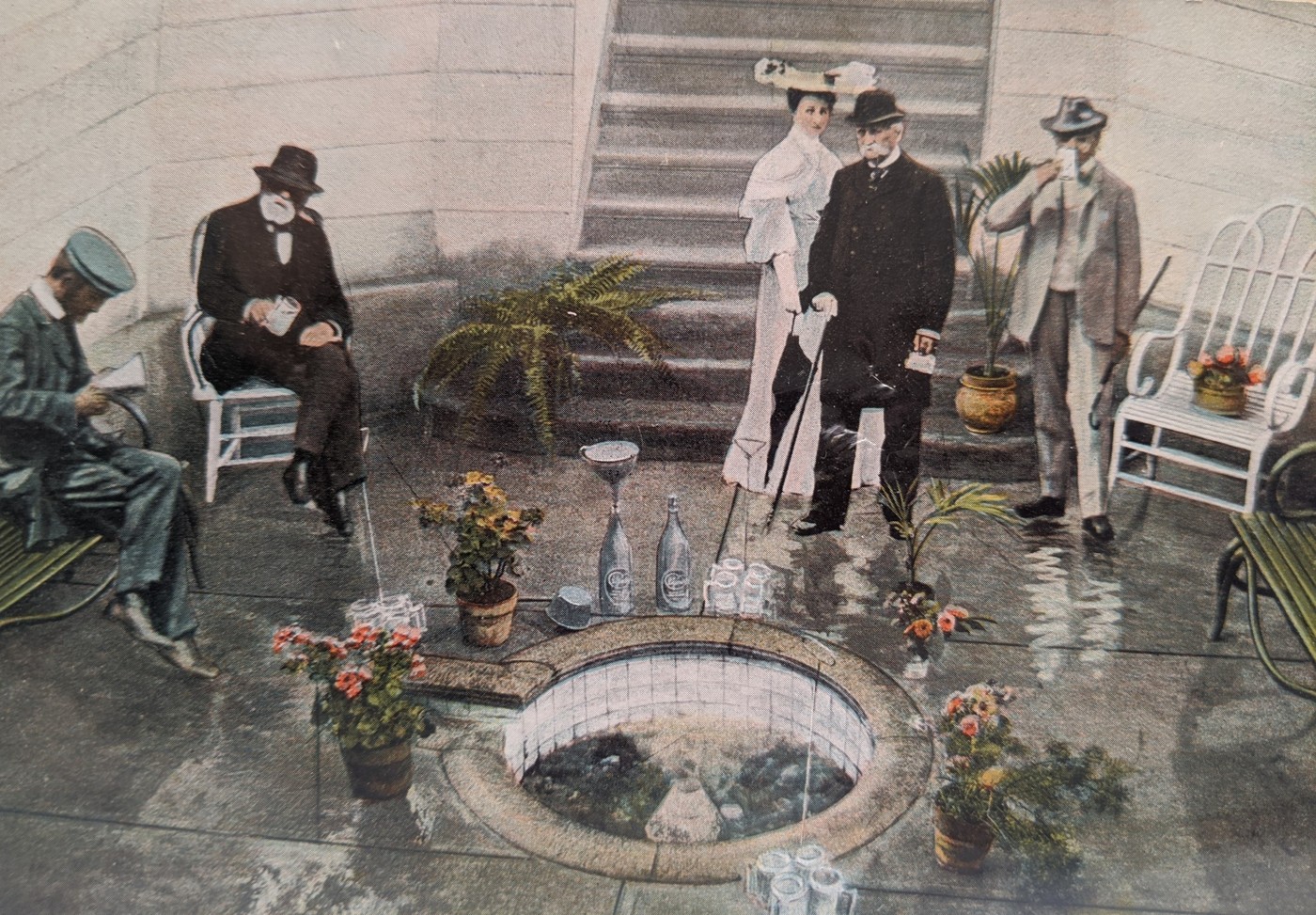

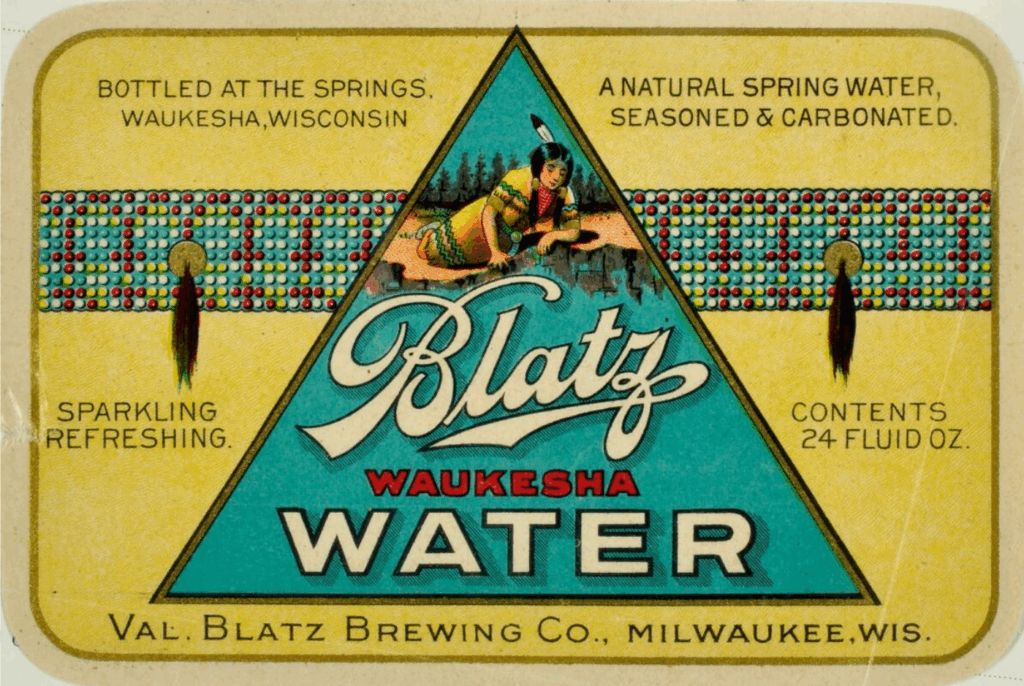

At the height of the Springs Era, twenty-five trainloads of people per day came to visit Waukesha. Many came for the famous healing waters, but others visited to enjoy recreational activities created by the springs industry that sprang up around the county. Some mineral spring water companies were so successful, they developed parks surrounding the springs. These parks hosted theaters, casinos, and hotels. Visitors enjoyed festivals, parades, musical programs, and other leisure activities. A main attraction in Waukesha, Silurian Springs Park was one of the largest in the county, second only to Bethesda Springs Park. An elaborate gazebo structure sheltered the naturally flowing mineral spring, and inside, dipper boys fetched water for visitors. Floral gardens, a lagoon, and small pavilions throughout the park surrounded the springhouse. At the park’s bandstands, weekly open-air orchestral concerts drew crowds of visitors, who listened to live music while enjoying spring water by the glass. Other amenities on the park grounds included an elegant bathhouse, a reading room, a casino, and a clubhouse. At the bottling plant, the Silurian Springs Company shipped water by the barrel and bottle. As tourism declined at the end of the Springs Era, the park closed to the public, but the bottling plant remained open for a few decades, continuing to produce bottled mineral water and sodas such as ginger ale and cherry phosphate.

The Springs Era began to decline in the early 20th century, gradually giving way a slow decrease in tourism and demand for medicinal spring water. Eventually, medical research discredited the healing powers of the miraculous Waukesha waters as scientists found new ways to treat diseases. Developments in transportation also slowed the tourism industry in Waukesha. When the automobile became more accessible, people were no longer limited by train routes and had more freedom in choosing travel destinations. Additionally, people no longer had to travel to the springs to get a taste of Waukesha waters with bottled water widely available in stores.

After a brief resurgence during prohibition, many mineral spring water businesses closed their doors, but a few continued to produce bottled water and beverages into the late 20th century. Today, most of the springs no longer exist, but some live on as historical landmarks and reminders of the period that shaped Waukesha’s history.

Written by Sara Mulrooney, February 2023.

SOURCES

J.W. Haight, Waukesha, the center of the Wisconsin lake region, popularly known as “the Saratoga of the West,” (Waukesha, Wisconsin: The Journal Print, 1888).

Cassie Nespor, Medical Treatments in the late 19th Century, (Youngstown, Ohio: Melnick Medical History Museum, 2013).

John Schoenknecht, From Prairieville to Waukesha: Columns Published in the Waukesha Freeman 2008-2010, (Waukesha, Wisconsin: The Daily Freeman, 2010).

John Schoenknecht, The Great Waukesha Springs Era 1868-1918. (Waukesha, Wisconsin: J.M. Schoenknecht, 2003).

James L. Small, “Mary Todd Lincoln Once Resided at Waukesha,” Milwaukee Sentinel, 11 February 1928.

Waukesha County Historical Society and Museum, “Victorian Life & the Springs Era,” https://www.waukeshacountymuseum.org/education/sprngs-era/

Waukesha County Historical Society

This object is part of the Waukesha County Historical Society Collection. Research for this object essay and its related stories was supported by the Waukesha County Historical Society in Waukesha, Wisconsin.