The legacy of abolitionists and anti-slavery figures didn’t end with the Civil War or the abolition of slavery, indeed many of the political and moral sentiments that fueled this movement for freedom continued on and inspired other political movements in Wisconsin, particularly the Progressive movement of the late-19th and early-20th centuries and subsequently the Wisconsin Idea. The Wisconsin Idea is a philosophical approach to politics that pushes for both a more academic government and a more active one. It encourages the use of academic experts as consultants by representatives but also encourages academics to be more active in their government and communities with an eye towards preventing concentrations of power and the injustices that they usually inflict upon individual rights. Similarly, both Abolitionism and Progressivism were concerned with the threat that concentrations of power posed to individual liberties and natural rights on both political and moral bases and both used these philosophies and ideas to work towards real political actions and change the injustices they witnessed. Just like the abolition movement before it, Progressivism and the Wisconsin Idea were concerned with concentrations of power that threatened individual liberties and used well-developed political and moral philosophies to address the injustices they saw through political organizing. Therefore, abolition in Wisconsin can be considered a part of the Wisconsin Idea tradition despite predating the formal naming of the concept.

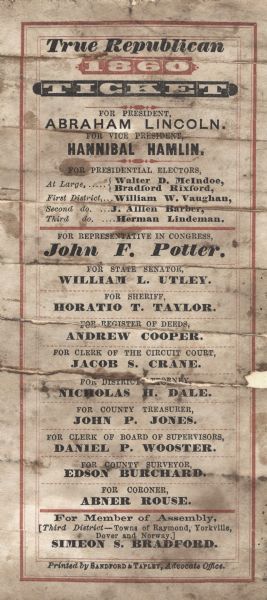

Anti-slavery movements in Wisconsin on the eve of the Civil War found their home in three main parties; the Liberty Party (founded in 1840), the Free-Soil Party (founded in 1848), and the Republican Party (founded in 1854). Each combined both moral and political arguments into their stances against the institution of slavery. Both the Liberty Party and the Free-Soil Party opposed slavery on the religious grounds that to hold another human being in a position of servitude was a sin, which meant that these groups denounced slavery on a moral basis as it went against the Christian faith. However, abolitionists in these parties also made the political argument that if slavery persisted or spread it would threaten the rights of white people—particularly white laborers. While the Liberty Party was primarily focused on the abolition of slavery, the Free-Soil Party had other platform concerns such as support for westward expansion. Despite these slight differences between the parties, they formed a coalition in order to advance their common goal of stopping slavery.

The Republican Party’s arguments against slavery are a bit more multifaceted simply because the party began as a coalition between various people from preexisting parties who were unhappy with the way their parties approached the issue of slavery. This meant that the party contained people with many different interests and opinions. The more “radical” coalition of the party held that slavery was sinful and opposed it on moral grounds, while the more “moderate” coalition was against it for fear that slavery would cause white Americans to lose their rights as well. But the Republican Party also had a third coalition, a more “conservative” faction concerned with the power slavery granted the southern states. This sect was concerned that if slavery continued or expanded it would only give the southern states a greater share of federal power than northern states in the national government. This was a much more political and self-interested argument against slavery, but it also shows a concern for the concentration of power in the hands of those who would abuse it. Thus, the movement against slavery can be seen as being a kind of ideological precursor to the political sentiments that would eventually be named the Wisconsin Idea.

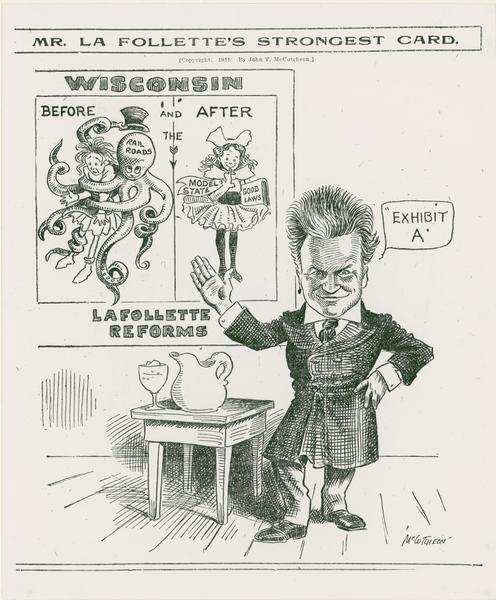

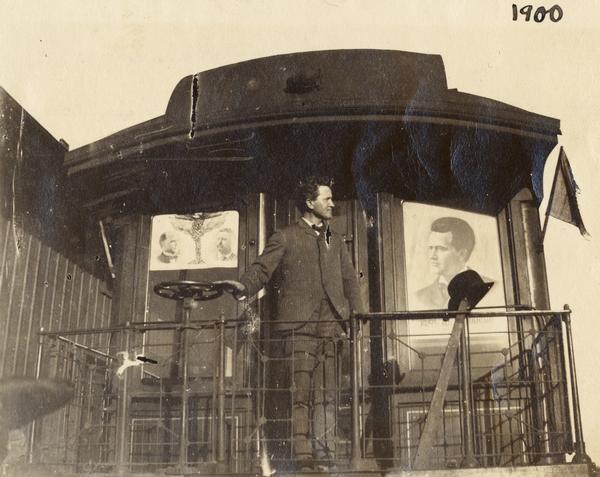

At the end of the nineteenth century, a progressive movement started to gain popularity throughout the country and nowhere was that more evident than in Wisconsin. Even Teddy Roosevelt recognized that “the Wisconsin reformers have accomplished the extraordinary results for which the whole nation owes them so much, primarily because they have not confined themselves to dreaming dreams and then to talking about them.” In the immediate aftermath of the Civil War the Republican Party began to gain popularity for the introduction of progressive internal improvements such as providing funding to support Civil War veterans and the improvement of internal waterways. These efforts were led by Philetus Sawyer, Henry C. Payne, and John C. Spooner who would become the party bosses. However, as time went on these men became entrenched leaders who fully controlled the party, something that would truly spark a progressive strain in Wisconsin politics led to a large degree by Robert M. “Fighting Bob” La Follette. One of La Follette’s main methods of disrupting the power of the entrenched politicians was the advocacy of direct primaries which would take the power of nominating candidates away from party bosses and give it directly to the people. Once he was able to win the nomination of his party and then the governorship, he continued to promote policies that would break up concentrations of power, particularly economic power. He introduced measures to control lobbying, increase railroad taxes, prohibit free railroad passes, and regulate railroad rates.

This kind of progressive politics became an important part of The Wisconsin Idea, particularly for members of the University of Wisconsin who played a critical role in its formalization. The Idea was in part inspired by the civic involvement of members of the University of Wisconsin, particularly John Bascom whom La Follette had studied under, and Charles McCarthy who had done his graduate work at UW and went on to be the state legislature librarian. There, McCarthy expanded the purview of his role from merely providing legislators information to also providing advice, thus starting a tradition of legislative policy informed by academics to work towards real political change. Yet Wisconsin politics began shaping the Wisconsin Idea long before the term came into use. It was thanks to those in the state who fought for the abolition of slavery as well those who stood up to concentrations of corrupt political power during the progressive era that this guiding principle was formed.

Written by Maria Serrano, October 2024.

Sources

John D. Buenker and William Fletcher Thompson. The Progressive Era, 1893-1914. Madison: State Historical Society Of Wisconsin, 1998.

Richard N. Current, The Civil War Era, 1848-1873. Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society, 2013.

Richard N. Current, Wisconsin: A Bicentennial History. New York: W.W Norton & Company, Inc, 1977.

Robert La Follette, La Follette’s Autobiography: A Personal Narrative of Political Experiences. Madison: Blied Printing Company, 1911.

Charles McCarthy, The Wisconsin Idea. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1912.

Davis Thelen, The New Citizenship: Origins of Progressivism in Wisconsin, 1885-1900. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1972.