The Platteville lead boom spanned from 1827 to 1849, bringing diverse groups of people and the mining industry to what would later become southwest Wisconsin. In 1827, galena (lead ore) was discovered in Platteville by frontiersmen exploring the Northwest Territory, which included the present-day states of Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, and part of Minnesota. This sparked a massive rush of lead miners and speculators hoping to strike it rich. Many of these early miners hailed from Cornwall, England. The Cornish transformed mining in the region by bringing with them the methods they had mastered back home. They constructed deep mines with ventilation and transportation and water pumping systems. The Cornish influence can still be seen today, as there is a Cornish miner on the Great Seal of the State of Wisconsin.

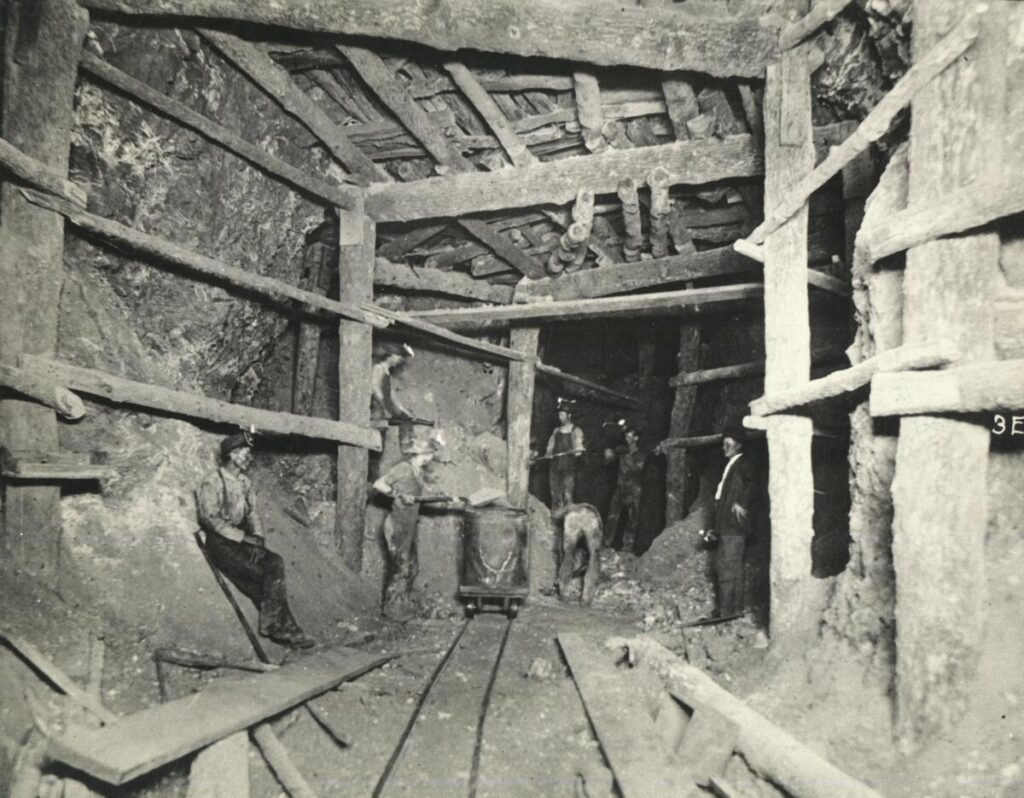

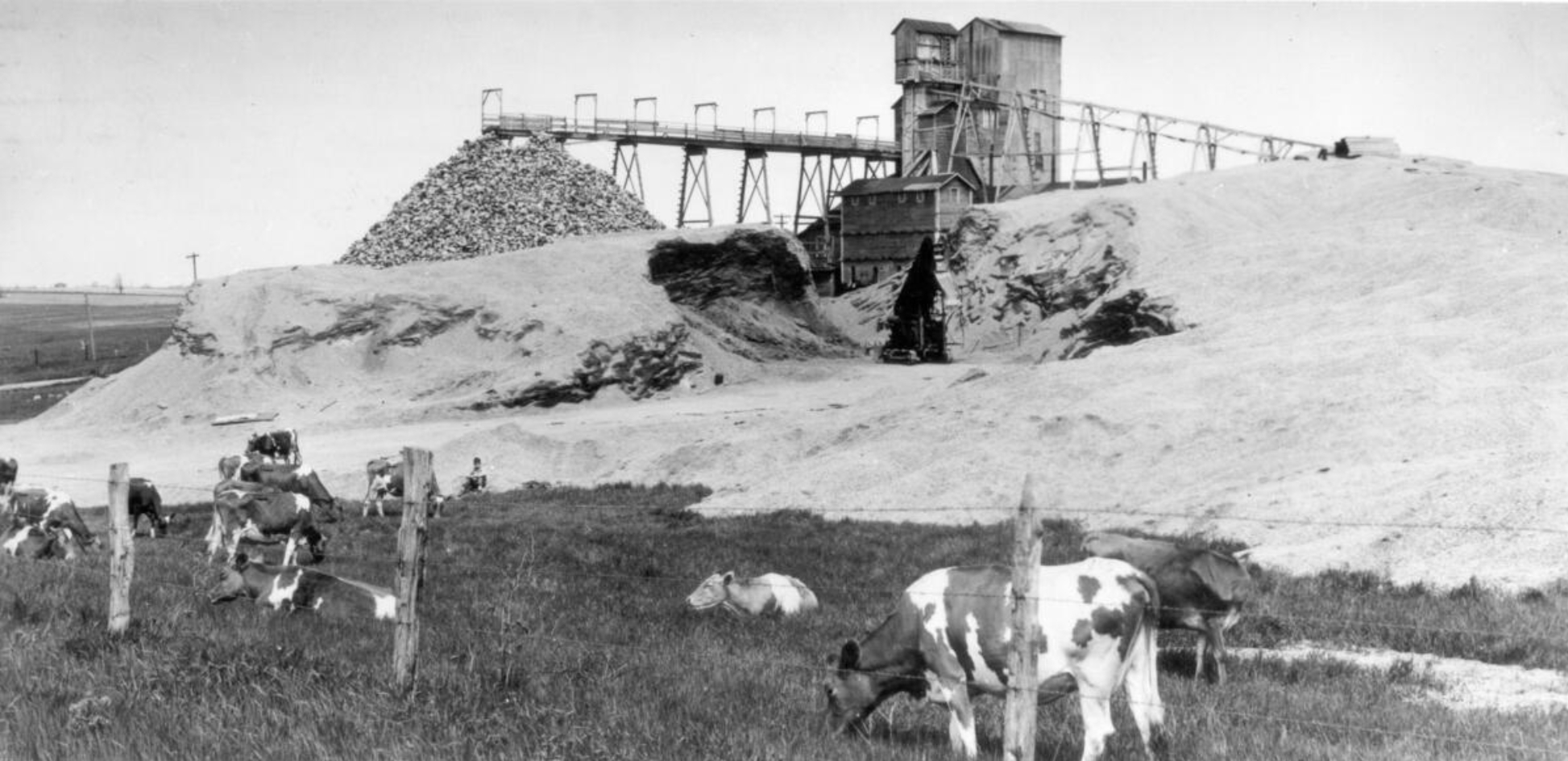

Platteville’s mining industry transitioned to primarily mining zinc ores in the 1850s because the lead deposits began to run out as the mines reached the “water table”. The water table is the depth underground at which groundwater sits behind the rock walls. At the depths just above and below the water table, the zinc ore Smithsonite is prevalent. Advancements in water pumping technology in the 1860s allowed miners to dig below the water table, where the zinc ore Sphalerite is located. Beginning in the 1870s, inventors from around the country began to improve rock drilling technology. Simon Ingersoll applied steam power to rock drills, while Henry Clark Sergeant applied his patented air compressor to power such drills. As a result of these inventions, large-scale zinc mining operations in Platteville became more efficient and, therefore, more profitable. Sphalerite was the primary mineral mined in Platteville from the 1860s to the close of the final mine in 1979.

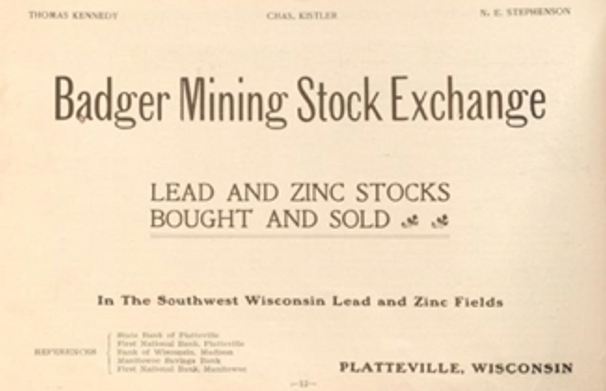

Platteville’s “zinc boom” began at around the turn of the century and spanned until the 1950s, revitalizing the town’s economy and population. The creation of new jobs in the mining industry led to population growth and increased economic opportunities. New businesses in Platteville like movie theaters and parking for cars instead of hitches for horses signified this change. Over 31 joint-stock mining companies were incorporated in Platteville alone in 1905 and 1906. A single stock of Empire Mining Co. from this era was offered at $600 ($18,000 in 2022 dollars) in Platteville’s stock market. Largely due to the mining industry, the population of Platteville grew from 2,740 in 1890 to 4,452 by 1910: an increase of 61.5%. Demand for zinc skyrocketed during World War I, World War II, and the Korean War. Zinc was needed for the production of certain metals and tires used by the military at this time. More jobs were created in Platteville’s zinc industry to bolster production to meet the high demand. As wartime demands waned and environmental regulations were enacted, the profitability of zinc mining in Platteville decreased. The final zinc mine in Platteville ended operations in 1979.

Platteville’s mining industry led many different groups of people to settle in the area. In addition to settlers from the Eastern and Southern United States, African Americans and Eastern European immigrants moved to Platteville. During the lead boom, wealthy mining speculators from Southern slave states arrived in southwest Wisconsin with their slaves. Although slavery was illegal in the Northwest Territory, the law was often not enforced. However, despite the fact that slaves were taken to Wisconsin against their will, it also became a place where escaped slaves could find a job and even forge a community. Some African Americans who had worked in the lead mining industry, such as George W. Jones’ former slave America Jenkins, settled at Pleasant Ridge. Pleasant Ridge was a racially integrated community near present-day Beetown in central Grant County (around 25 miles west of Platteville) that served as a refuge for escaped slaves. The remaining slaves in southwest Wisconsin gained their freedom by 1840.

Eastern European immigrants from Hungary and Bulgaria settled in Platteville from the 1890s to the 1920s to work in the booming zinc mining industry. These immigrants were mostly young, single men who moved to the region to find temporary work and earn money to send back home to their families. Many of the Eastern European immigrants in Platteville lived in “boarding houses”, communal living spaces owned by local property owners and rented out at low prices. Unfortunately, these immigrants faced discrimination in Wisconsin and the United States more broadly. This anti-immigrant sentiment led to national legislation which severely limited immigration from Eastern Europe, among other places.

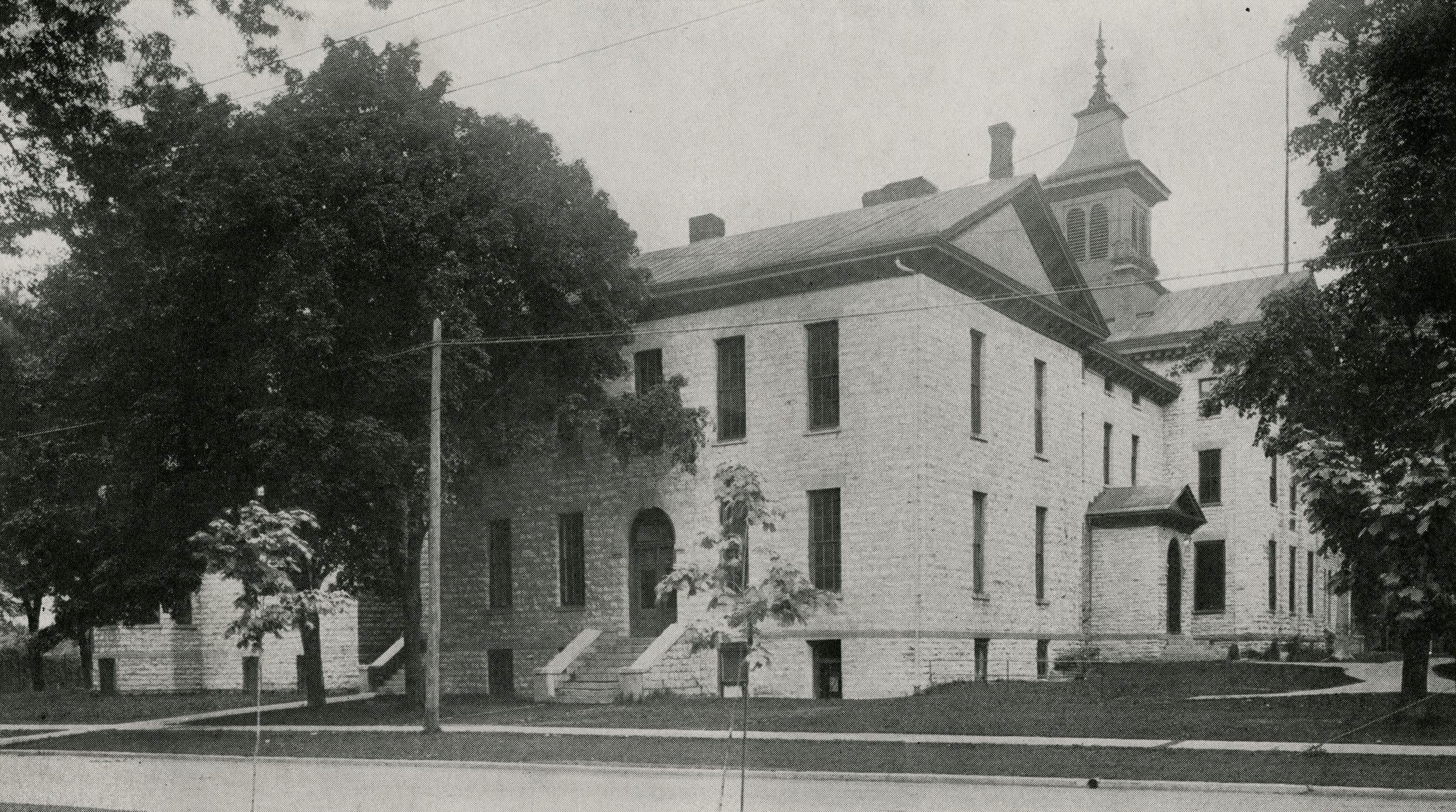

Platteville’s mining legacy has had a lasting impact on Wisconsin. The present-day University of Wisconsin-Platteville has roots in the Wisconsin Mining Trade School, which was established in 1907 to provide specialized education in the new inventions required for commercial zinc mining. The Mining School became the Wisconsin Institute of Technology in 1939 and merged with the Platteville State Teachers College in 1959. The college underwent two name changes before becoming the University of Wisconsin-Platteville in 1971. Today, UW-Platteville continues to be known for its engineering education.

Mining is a revered tradition in Platteville that continues to take on meaning through landmarks and celebrations. The Platteville Mound, a relic of the unglaciated Driftless Area, rises above the horizon three miles east of Platteville. On the west side of the mound facing Platteville is the world’s largest hillside letter “M”, which stands for “mining”. Completed in 1937 by Mining School students, the “M” measures 214 by 241 feet and is made up of 400 tons of whitewashed stone. The “M” takes center stage in an annual tradition for UW-Platteville’s Homecoming when it is lit with lanterns and hosts a fireworks show.

The Mining Museum in Platteville, opened in 1971 and continues to educate visitors on Platteville’s mining history today. On the museum grounds, visitors can ride on a railroad and observe what the operations of a mine looked like. Most notably, visitors can enter the Bevans lead mine: an excavated former lead mine from the 1840s. The mining industry shaped Platteville into a vibrant community with an enduring legacy, while bringing diverse groups of people and economic opportunity to the state of Wisconsin.

Written by Liam Reinicke, December 2022.

SOURCES

Karel D. Bicha, “Hunkies: Stereotyping the Slavic Immigrants, 1890-1920,” Journal of American Ethnic History 2 no.1 (1982): 24. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27500236.

Castello N. Holford, History of Grant County Wisconsin. Marceline, Missouri: Walsworth Pub. Co., Inc.

The Mining and Rollo Jamison Museums, “Mission, Vision, History & Governance.” https://mining.jamison.museum/history/

The Mining and Rollo Jamison Museums, “Virtual Fieldtrip,” 2021. https://mining.jamison.museum/virtual-school-field-trip.

The Mining and Rollo Jamison Museums, “Wisconsin Lead and Zinc Mining History,” 2022. https://mining.jamison.museum/wisconsin-lead-zinc-mining-history/

Eugene R.H. Tesdahl, et al. “African American Lead Miners in Wisconsin,” The Mining and Rollo Jamison Museums, Platteville, Wisconsin, online exhibit. https://mining.jamison.museum/african-americans-in-the-lead-mining-district/

University of Wisconsin-Platteville, “History,” Accessed December 2022. https://catalog.uwplatt.edu/undergraduate/about-uwplatteville/history/.

Wisconsin Historical Society, “Pleasant Ridge: A Community of Black Farmers in Wisconsin,” Historical Essay. https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS1576.