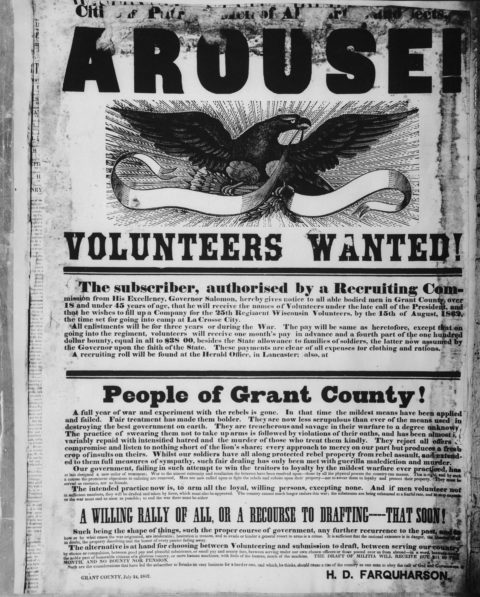

Following the South’s attack on Fort Sumter in 1861, Wisconsin, and the North as a whole, experienced a surge in patriotism and an eagerness to fight for the North, offering more volunteers than were needed. Due to the flood of new recruits, the U.S. government stopped recruiting troops. As the fighting continued, however, casualties mounted, and the Union army struggled; the former optimism was clearly seen as a mistake. The North needed more troops but now there was far less enthusiasm to enlist. During the summer of 1862, President Lincoln called for 600,000 additional men to join the fight. Wisconsin’s quota was 11,804 soldiers and they were to be ready in 15 days.

Wisconsin’s Governor, Edward Salomon, struggled to meet the quota. Too few men were volunteering for the war so Governor Salomon reluctantly called for a draft of all able bodied men between the ages of 18 and 45. Most counties in Wisconsin managed to meet their quotas with volunteers, but one county in Wisconsin had specifically lagged behind in volunteer recruits: Ozaukee County. Consequently, their draft quota was particularly high.

Ozaukee County responded to the call for troops with notable reluctance. Its opposition to the draft was due to a few reasons: Ozaukee County had not supported Lincoln and was populated by mostly Catholic immigrants, many of whom had fled their countries specifically to avoid mandatory conscription. Secondly, Ozaukee County was largely a rural county, and as such, many relied on the harvest time to subsist. Drafted farmers would miss the most crucial time for farming. Whatever reason for their distaste for the draft, on November 10, 1862—the day of the draft—tempers were running high and many were ready to oppose the draft with full force.

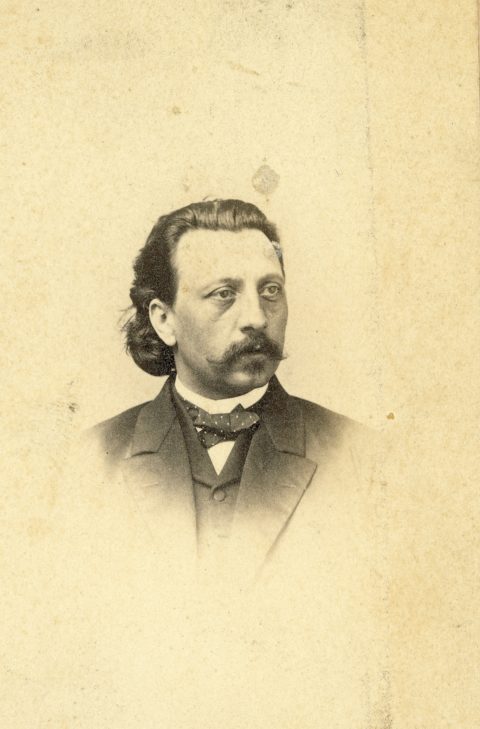

William Pors, local lawyer and draft commissioner for the City of Port Washington, was charged with conducting the draft using the draft drum. He knew there was opposition to the draft and he knew that there could even be violence. A newspaper article from the time reported that he opted to go forward despite the personal threats to his safety because he viewed it as a matter of honor. That morning, he arrived at the local courthouse to begin the draft where he was met by an angry crowd with a large banner saying “No Draft.” He was told that if he proceeded he would be a “dead man” but he calmly began the draft process. As he began reading the names of those selected, a mob of angry people rushed him beating him with clubs as well as rocks. The Sheriff finally urged Pors to “fly for his life” and he fled, as the rioters—men and women both—tore his clothes, pulled his hair, hurled him down the courthouse stairs and threw rocks after him, hitting him hard enough in the head that he was knocked down.

After beating Pors, they proceeded to destroy the draft box, and the official draft records. Pors, injured and bleeding, made it to the nearby post office and took refuge in the basement. Some of the rioters demanded the post office clerk turn Pors over to them, threatening to hang them both. When the clerk claimed Pors was not inside, they returned to the courthouse to destroy the enrollment lists, then the mob proceeded to seek out the homes of several Republicans and an Abolitionist, destroying their property. They went to Pors’ home, as well. Pors’ wife, three year old child and a servant barely had time to escape before the mob broke in and destroyed many of the family’s possessions, including Pors’ personal library, photographs of his deceased parents, linens his wife had brought from Germany, even killing his pet canaries and throwing a cradle out the window. The house and gardens were ruined.

Expecting an armed response, the mob took the cannon used for the County’s 4th of July celebration, loaded it with the only cannon ball in the entire town, and aimed it towards Lake Michigan. Unfortunately for the rioters, the armed response was swift and more extensive than the rioters anticipated. They were quickly arrested and more than 100 of them were placed at Camp Randall where they remained for a year.

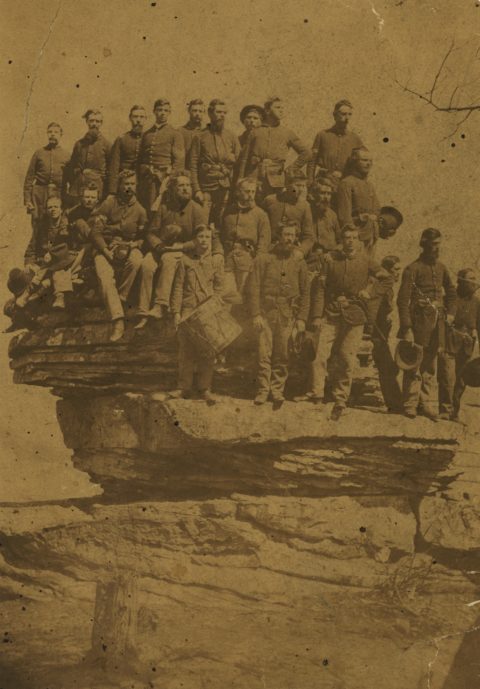

Of the 4,537 men drafted in Ozaukee County, only 1,739 entered the army. Of the 38,495 drafted in Wisconsin, only 6,812 reported for duty. As the war continued, however, Lincoln gained more support. In the end, 91,000 Wisconsinites in total served in the Civil War against the South; they had a dramatic impact on the war most notably in the Iron Brigade, so named by General McClellan, who was struck by their tenacity and bravery.

The Ozaukee county riots had a profound effect on how the Wisconsin State government would respond to potential dissent in the future. This was evident in Washington County which, like Ozaukee County, was made up of almost entirely German Immigrants. It was a predominantly farming community, as well as anti-Republican. Because of a lack of enthusiasm with the war, Washington County put forward fewer volunteers for the war than any other county in Wisconsin. Because of this, the draft quota was high for Washington County. Washington County also spent the most to avoid the war at all costs. Newspapers were filled with ads seeking people to take their place in the draft. When E. Gilson, the draft commissioner for the county began the Washington County draft proceedings, a riot broke out. This riot, however, was squelched almost immediately, as the state dispatched six companies of soldiers to maintain the peace and the draft resumed. In Ozaukee County, the draft resumed a few days after the riots. William Pors and his family did not return to Port Washington.

Written by Jack Fain, June 2017.