Madison’s beloved Camp Randall Stadium holds a rich history many football fans are unaware of as they pass under the iconic Memorial Arch entrance. A box of chlorinium, tucked away in the Wisconsin Historical Society archives, opens the window to Civil War-era Camp Randall. The use of a chlorinium disinfectant at Camp Randall is evidence of evolving sanitation practices during war and their impact in Wisconsin during the late 19th Century.

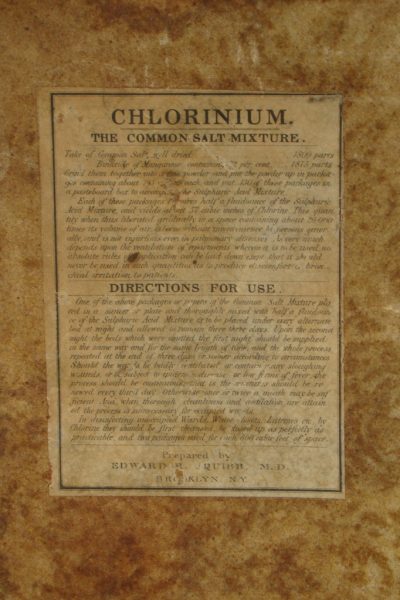

The chlorinium box, made of cardboard and covered with brown textured paper, features a faint swirl design with a bright green coloring inside the lid. The chlorinium itself is a finely ground black powder, wrapped in beige paper. The packets are carefully bundled in stacks of ten, wrapped in blue ribbon and sealed with a red wax. What the makers called ‘chlorinium’ was a mixture of two common minerals, manganese dioxide and sodium chloride (ordinary table salt), which were packed with a small container of sulfuric acid. When the acid was mixed with the powder, chlorine gas was created, which could be used as a disinfectant. These packets of chlorinium were imported to Camp Randall from Brooklyn, NY between 1861 and 1865.

Florence Nightingale’s work inspired the implementation of sanitary measures throughout Union Army hospitals during the Civil War. As a nurse for the British military in the Crimean War during the 1850s, she experienced first-hand the gross neglect and unsanitary conditions in military hospitals that held wounded soldiers. Nightingale suspected “bad air” and poor ventilation as contributing factors to respiratory diseases that commonly plagued the British troops, and she implemented various sanitation practices such as laundry in hospitals and better ventilation in attempt to prove her theory. She kept statistics on hospital sanitation and published her results in the book Notes on Hospitals in 1859. The Union’s military doctors consulted her work and applied her methods during the Civil War, maintaining her focus on medical sanitation.

The dire condition of ill soldiers was strongly criticized by many Americans during the war years, and the civilian-led U.S. Sanitation Commission pushed for reforms of military hygiene regulations in 1862. With cleanliness as a new priority, the hospital at Camp Randall imported goods from Dr. Edward R. Squibb’s private East Coast pharmaceutical practice to help advance sanitary standards, including chlorinium.

Dr. Squibb had left his position as a physician at Brooklyn Naval Hospital to pursue his passion as a pharmacist. The Union Army chose his practice in particular because of his strong military background, the practice’s priority of developing high quality products, and because in the 1860s, Dr. Squibb became a leader in championing drug regulations. During the Civil War, Dr. Squibb’s private practice supplied one-twelfth of medicine bought for the Union Army.

A box label on the Squibb product details its contents and directions for use. The first paragraph notes the space needed for the chlorinium to be used safely and warns against its use in harmful quantities. The second paragraph gives directions on how to make the chlorinium mixture, to be placed under every other hospital bed for three days. The disinfectant was also used to clean unoccupied wards, water closets, and latrines. Following the end of the Civil War, the Wisconsin Pharmaceutical Association preserved the box in their collections. The Association eventually donated the artifact to the Wisconsin Historical Society in 1914.

The use of chlorinium at the Camp Randall hospital demonstrates the Union Army’s developing sanitation practices. The Union used these methods not only in field hospitals but also at training facilities such as Camp Randall. These practices became part of the beginning of a new era in the history of medicine with Camp Randall at the forefront of these changes in the late 19th Century.

Written by Chloe Bonchonsky, September 2023.

Sources

American Medico-surgical Bulletin. United States: Bulletin Publishing Company, 1893.

Devine, Shauna. “‘To Make Something Out of the Dying in This War’: The Civil War and the Rise of American Medical Science.” Journal of the Civil War Era 6, no. 2 (2016): 149–63. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26070401.

Thompson, Tommy. “‘Dying like Rotten Sheepe’: Camp Randall as a Prisoner of War Facility during the Civil War.” The Wisconsin Magazine of History 92, no. 1 (2008): 2–15. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25482093.

Mahr, Michael. “The Squibb Story.” National Museum of Civil War Medicine. Accessed July 11, 2023. https://www.civilwarmed.org/squibb-story/

Mattern, Carolyn J. Soldiers When They Go: the Story of Camp Randall, 1861-1865. Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1981.

Meier, Kathryn Shively. “Soldiers and Official Military Health Care.” In Nature’s Civil War: Common Soldiers and the Environment in 1862 Virginia, 65–98. University of North Carolina Press, 2013. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5149/9781469610771_meier.7.

McDonald, Lynn. “Florence Nightingale, Statistics and the Crimean War.” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A (Statistics in Society) 177, no. 3 (2014): 569–86. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43965414.

Zimm, John. “‘ON, WISCONSIN!’: Celebrating Camp Randall.” The Wisconsin Magazine of History 102, no. 1 (2018): 28–37. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26541154.