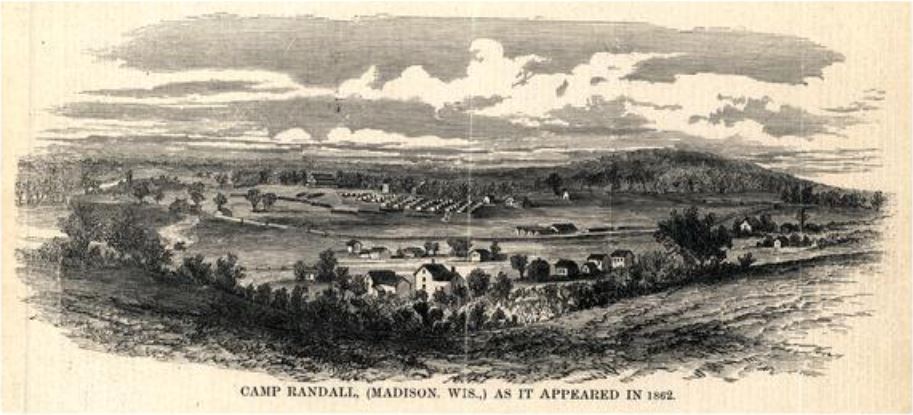

Madison residents crowded outside the local railroad station in April of 1962 and awaited the arrival of Confederate prisoners to be held at Camp Randall. Surprisingly, the Northerners met the newcomers, many among which were riddled with disease, with sympathy and curiosity rather than standard enemy hostility. Those of the prisoners strong enough to walk slowly made their way to their new residence, while others in worse condition were carried on stretchers. This first interaction foreshadowed the unlikely relationship formed between them during the prisoners’ two-month stay at Camp Randall during the height of the Civil War. The site already faced overwhelm by an influx of Wisconsin soldiers in the preceding months, leaving undesirable conditions for the last minute arrivals. The locals did their best to mitigate the Confederates’ suffering by donating supplies, volunteering assistance, and condemning the camp’s state in local newspapers.

On February 28, 1862, a fierce battle broke out in Kentucky at a Confederate-held fortification in the middle of the Mississippi River, known as the Battle of Island No. 10, the fight ended with a Confederate surrender on April 8, 1862. Following the battle, the Union Army regiment detained the surviving Confederate soldiers, and transported them up the Mississippi River as prisoners of war. Union orders consigned some prisoners to Camp Douglas in Chicago (one of the larger Confederate prison camps in the North), and 1,156 prisoners (a majority of which were from the First Alabama Regiment of Volunteer Infantry) to Camp Randall necessitating a partial conversion to a temporary prisoner of war camp at the year-old troop training facility. The harrowing journey north cost numerous Confederate prisoners their lives. Many of those lucky enough to survive arrived severely ill from the unforgiving conditions of war and travel. Soldiers on both sides of the Civil War fell ill with pneumonia, typhoid fever, and other infectious diseases. The losses felt by the Union and Confederacy became a common ground between enemies, and out of shared loss and grief grew unexpected compassion for the other side.

The surviving sick Confederates were crowded into Camp Randall’s hospital upon arrival. The building had undergone expansions and renovations earlier that winter to accommodate an increasing number of patients. Limited barracks space meant soldiers faced living in tents, exposed to the unforgiving cold of Wisconsin’s winter, and many found it difficult to keep disease at bay. In a period of just two months, about 200 Confederate prisoners received medical treatment at Camp Randall, and while staff attempted to maintain new medical sanitary standards by importing disinfectants such as chlorinium, the hospital remained overwhelmed. As the use of disinfection at the time was not widespread, its presence at the hospital shows an uncommon effort to improve sanitation practices. A local physician, Dr. Joseph Hobbins was placed in charge of the hospital, working alongside doctors of the Wisconsin 19th Regiment, Homor C. Markham and Thomas J. Linton, and a Confederate army surgeon, Dr. William A. Martin. This diverse team of medical professionals is proof of a collective effort across enemy lines to help the suffering patients at Camp Randall hospital.

During the Confederates’ first weeks at Camp Randall, many died. The mortality rate was alarmingly high. While the hospital registry records these deaths, the treatment of prisoners and the specific causes of their deaths are less certain. Assistant Quartermaster Joseph Potter, a visitor from Camp Douglas, noted the dismal conditions of the Camp Randall hospital. In early May 1862, the Wisconsin Daily State Journal reported on the “gross neglect” at the hospital with hope that the conditions would be remedied. Dr. Martin pointed out the article disregarded a key fact, many of the Confederate prisoners were already doomed by sickness caught prior to their arrival at Camp Randall. He assured the public the doctors were treating the ill to the best of their ability. Despite the newspaper’s questionable assumptions, the claims brought attention to the condition of those suffering so far from their southern homes. Locals were moved to show kindness to the prisoners by offering supplies of newspapers, jellies, pudding, and brandy.

At the end of May 1862, the Union ordered the Confederate prisoners to Camp Douglas, a larger prisoner of war camp in Chicago, Illinois. Those too ill to travel followed close behind in the summer months, bringing an end to Camp Randall’s era as a Civil War prison.

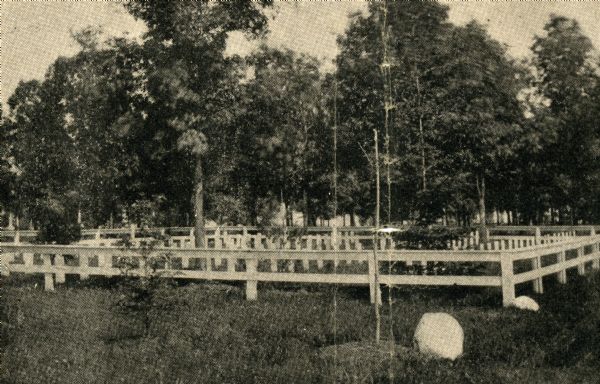

One-third of the ill Confederates did not survive their stay at Camp Randall, and the dead were buried together in Madison at the Forest Hill Cemetery. A Louisiana-born local resident, Alice Whiting Waterman took an interest in the soldiers’ final resting place, taking care of the grounds until her passing 35 years later. Wisconsin governor Lucius Fairchild along with other Madison officials recognized her efforts and offered their help. The Wisconsin governor began to pay tribute annually to the fallen enemy soldiers by decorating their graves on Memorial Day, giving rise to a new tradition. Fairchild was the first northern governor to perform this act of honor, another salute to the unique relationship among enemies of the Civil War in Madison.

Despite a difficult journey north to a part of the country against which they were waging a war, efforts were made to welcome and care for Confederate prisoners in Madison. The civilian turnout in aid of the suffering enemy soldiers and local news outcry for better conditions showed the community’s compassion. While most had not encountered Confederate soldiers prior to their arrival in Madison, their similarities suggested they weren’t all that different. The use of disinfectants like chlorinium signaled the efforts made by Camp Randall hospital to improve sanitary conditions, a novelty during this period. The Confederate prisoners’ short stay at Camp Randall illustrates a surprising demonstration of empathy for the enemy during the Civil War.

Written by Chloe Bonchonsky, September 2023.

Sources

Thompson, Tommy. “‘Dying like Rotten Sheepe’: Camp Randall as a Prisoner of War Facility during the Civil War.” The Wisconsin Magazine of History 92, no. 1 (2008): 2–15. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25482093.

Titus, William A. “A Wisconsin Burial Place of Confederate Prisoners of War.” The Wisconsin Magazine of History 36, no. 3 (1953): 192–94. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4632558.

Zimm, John. “‘ON, WISCONSIN!’: Celebrating Camp Randall.” The Wisconsin Magazine of History 102, no. 1 (2018): 28–37. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26541154.