The lead mining industry of the 1830s and 1840s brought miners from Cornwall, England, a county of South West England, to southwestern Wisconsin. The miners brought Cornish traditions like the pasty, a filling food for hungry miners. The availability of pasties today demonstrates the lasting traditions of early European immigrants in Wisconsin.

Pasties are folded pastries filled with meat and vegetables. Traditional ingredients include beef, rutabagas, onions, and potatoes. They are small enough to fit in one hand but contain enough calories to be a hearty lunch for a hardworking miner. Since meat was considered a luxury in those times, pasties contained mostly vegetables. In addition to holding the filling inside, the thick crust of the pasty helped the filling retain heat long enough that they were still warm by lunchtime. The pinched crust made a convenient handle- perfect for miners’ dirty hands.

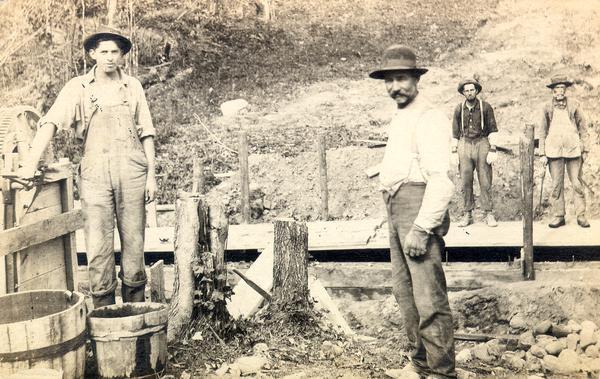

In the 1830s, the lead-mining industry took off in southwestern Wisconsin. Most settlers came to Wisconsin to mine galena, the mineral used to make lead. The miners founded settlements with names like New Diggings, Miner’s Grove, and Mineral Point. The settling of the frontier skyrocketed demand for lead and before lead poisoning was discovered, lead was used for water pipes, paint, and many other common items. Immigrants from Cornwall, who had experience working in mines, flocked to Wisconsin to take advantage of the work opportunities. The immigrant miners brought traditions from their home countries, like pasties.

The crust of the pasties played an important role in the miners’ superstitions. One superstition was that the lead mines were inhabited by the spirits of deceased miners, called “Knockers” or “Tommyknockers.” To keep the “knockers” happy, miners would leave the crusts of their pasties in the mines for the knockers to eat. They believed it was in their interest to keep the knockers happy: superstition said that the offering would encourage the knockers to show them where to look for deposits of galena.

In Wisconsin, lead mining peaked in the early 1840s. When demand for lead decreased, many miners moved on to Michigan’s Upper Peninsula to work in the copper or iron mines or participated in the California Gold Rush. Today, you can find pasties in the former mining regions of southwestern Wisconsin and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, a continuing tradition of Cornish culture.

Listen to a National Public Radio segment on the tradition of pasty-making in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. Transcript available here.

Written by Nick Ostrem, October 2018.

This object is part of the Wisconsin Historical Museum Mini Tour at the Wisconsin Historical Society. Teachers, download the Pasty Lesson Plan!

Essay by Nick Ostrem

Produced for Wisconsin Life by Jane Genske

Imagine this: It’s early morning in a small Wisconsin town about a century ago. The sun hasn’t risen, but parents bustle around the kitchen. They’re making pasties.

One’s for dad, who’s preparing for a day in the mines.

Some are for the children, who are about to head to their one-room schoolhouse.

The extras are for mom, who will warm them up for dinner tonight.

Listen below to the segment from Wisconsin Public Radio’s Wisconsin Life.

Maureen McCollum: Is there really anything better than a buttery, flaky pastry filled with meat and vegetables, or perhaps just vegetables for our vegetarian friends? The pasty has long been a staple in certain Wisconsin communities and has a rich history with a particular group of workers. Jane Genske went to learn more about the role of pasties in Wisconsin history.

Jane Genske: Imagine this: it’s early morning in a small Wisconsin town about a century ago. The sun hasn’t risen, but parents bustle around the kitchen. They’re making pasties. One’s for dad, who’s preparing for a day in the mines. Some are for the children, who are about to head to their one-room schoolhouse. The extras are for mom to warm up for dinner tonight. The pasty is convenient, handheld and delicious. It’s a flaky, buttery pastry folded over, pinched at the crust, bursting with meat and vegetables. The more traditional fillings might include beef, rutabagas, onions, and potatoes.

Customer Recording: Okay, yeah, could we do two of the Greek.

Jane Genske: Joe’s Pasty Shop has been making these savory pies for decades. Jessica Lapachin opened a location in Rhinelander 15 years ago. She talks about the business’s history while her husband, Larry, chops onions.

Jessica Lapachin: So Joe’s Pasty Shop is a third-generation pasty business. My family opened up Joe’s Pasty Shop in Ironwood, Michigan in 1946

Jane Genske: Miners from Cornwall, England flocked to Wisconsin in the 1800s. They settled in places like Mineral Point and Miners Grove as more lead was needed for things like paint, pipes, and lead shot. Cornish miners brought their mining expertise for extracting Galena, which is a mineral used to make lead. They also brought a piece of their European culture, the pasty.

Jessica Lapachin: It’s a portable meal that the Cornish miners would have taken down into the mine, a handheld meal that they could hold with dirty hands. And they would hang onto the crimp of the crust, eat the center and throw the crimp away.

Jane Genske: While the pasties kept the miners nourished, they also thought the scraps could bring them good luck.

Jessica Lapachin: So there’s a superstition in mining culture of these spirits that live in the mine. They’re called Tommy Knockers. And so they would do things like move tools around or hide things from the miners. And so, you know, the miners started to think, well, we have to appease them. Let’s give them the crust of our pasties. So they would toss that into the corners of the mine. So…

Jane Genske: When the demand for lead decreased in southwestern Wisconsin, many Cornish miners moved to the Upper Peninsula to work in copper and iron mines. Pasties became a family tradition passed on from generation to generation. Lapachin says hers isn’t the only family with a pasty story.

Jessica Lapachin: And it’s a very familiar, memorable food for people. People are really passionate about their favorite pasty and their pasty stories and the way their grandmother made them.

Jane Genske: Inside Joe’s is regular customer, LJ Summers. He didn’t grow up with pasties, and had his first one when he moved to Rhinelander.

LJ Summers: In the past year, since I’ve lived in the neighborhood, and everybody was like, “You need to go get a pasty.” And so I did, and I’ve been hooked ever since.

Jane Genske: Summers is now a pasty fanatic. He can’t stay away from the shop for more than a week.

LJ Summers: Well, I like the Greek pasty a lot. That’s definitely my favorite. And then my new favorite recently is the Cornish one, because that one goes unannounced, like, I feel like nobody pays attention to it because of the rutabagas. People are scared of rutabagas.

Jane Genske: Even after the fall of the mining era in Wisconsin, people’s love of pasties lives on.

Maureen McCollum: That story about pasties in Wisconsin came from Jane Genske. She’s a UW-Madison student working on an internship for Wisconsin Life and Wisconsin 101 which tells the history of the state through objects. Wisconsin Life is a co-production of Wisconsin Public Radio and PBS Wisconsin, in partnership with the Wisconsin Humanities Council. Additional support comes from Lowell and Mary Peterson of Appleton. Want to make sure you catch every Wisconsin Life story? Subscribe to our podcast feed and find more Wisconsin Life at wisconsinlife.org and on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. I’m Maureen McCollum.

This Post Has One Comment

Comments are closed.

Thank you for this history lesson on Wisconsin and pasty. My father’s mother used to make delicious pasty. It was interesting learning about this dish that my Grandma used to make.