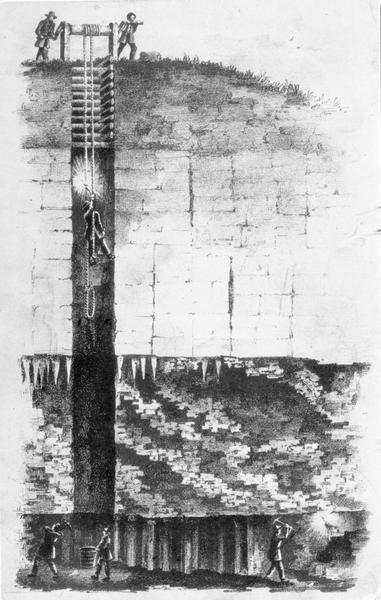

This is a machine used to lower and raise miners and materials through mine shafts in the lead mining region around Platteville, Wisconsin. Made from wooden supports with a wooden barrel shaft and crank attached to a rope with a bucket, a windlass like this is deceptively simple. Cheap to build and easy to maintain machines such a this one were vital to the development of Wisconsin’s lead mining industry in the nineteenth century.

This windlass was used by an African American lead miner and farmer named James D. Williams at his mine near Rewey, Wisconsin. Typically miners built their own windlasses, and it is likely that Williams built the one used in his mine. Like other miners, Williams used this windlass to raise and lower tools, ore, explosives, and miners into and out of the mine. Looking closely at the wear on the crank handle, we can imagine the thousands of hours of labor Williams invested in his mine, and the thousands of pounds of material he lowered and raised each year. In places it is so worn, you can almost see the places where each finger held the handle.

James D. Williams arrived in the Pecatonica Welsh settlement north of Platteville and west of Mineral Point in the late 1860s. Roughly a decade after he arrived in the region, Williams purchased a lead diggings and farm in Rewey. He operated the mine for the next twenty years or so, and continued to farm until his death in 1903.

Although Williams came to the Platteville area as a freeman after the end of the lead rush, during the height of the lead rush (1827-1849) at least one hundred enslaved African Americans were brought to Wisconsin to work in the mines. During that period slavery was prohibited in this region, but the law was often overlooked or loosely enforced. Of the approximately 100 African Americans who worked with lead in nineteenth-century Wisconsin, most gained their freedom by 1842. By 1860, the African American population in Wisconsin had grown to 1,200, all whom were free. This windlass helps introduce us to both the history of slavery in Wisconsin’s mining region, and the experiences of James D. Williams and other African American miners in the region.

Written by Deja Roberson and Winifred Redfearn, August 2018.

Hawks Inn & Delafield History Center

This object is in the collection of the Mining & Rollo Jamison Museums of Platteville, Wisconsin. Research for this object essay and its related stories was supported by the museum.