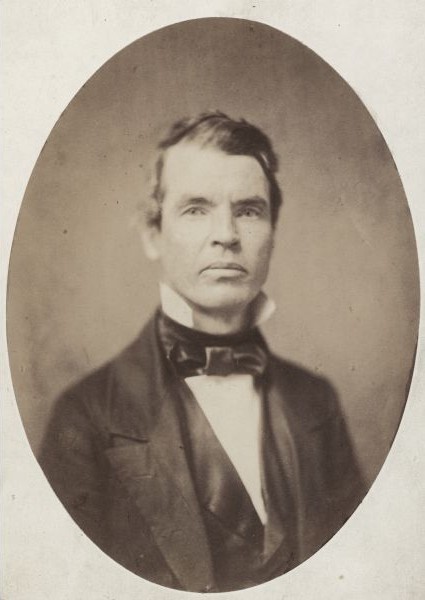

As immigration to Wisconsin swelled in the 1840s, so, too, did the state’s scientific and technological community, with innovations across industries ranging from agriculture and manufacturing to geology and environmental studies. Among Wisconsin’s first “pioneer scientists” was Increase A. Lapham, a young canal engineer and surveyor from New York who came to the state in 1836 at the age of 25. While Lapham had little formal education, he already had roughly eight years of experience in cartography as a professional surveyor since the age of 17. Over time, Lapham became one of the state’s most notable scientists and naturalists, officially surveying much of the southern half of Wisconsin for the first time, cataloging American Indian effigy mounds, and founding the United States Weather Bureau, among numerous other accolades.

While Lapham spent much of his first decade in Wisconsin surveying the state and mapping for the U.S. Geological Survey, he also began recording meteorological measurements beginning shortly after his arrival in 1836. His true pioneering work in the field began in 1849, when he began providing official weather reports to the Smithsonian Institute in Washington D.C. Lapham quickly realized just how significant a factor the weather was to Wisconsin pioneers, many of whom were farmers. It was also crucial for shipping companies on the Great Lakes, which had grown exponentially as the country expanded westward. Lapham established a weather observation post for the Smithsonian in Milwaukee at his home (though since demolished, the home stood near to the present-day Fiserv Forum). Using early meteorological tools like a barometer, a barograph, and a rain gauge, Lapham and his assistants recorded atmospheric measurements twice daily and relayed them to the Smithsonian Institute. The Institute established other observation posts throughout the United States, providing a steady stream of meteorological information to the Smithsonian Institute.

Coinciding with the growth of weather observation was the invention of the electrical telegraph, a small machine that provided a way to send information nearly instantaneously across the country through wires. Lapham saw an opportunity to help Wisconsin farmers and protect shipping on the Great Lakes: if he could get information from weather observation stations around the country, he could reasonably predict the weather that would be coming towards Wisconsin, and thus Wisconsinites could prepare themselves for the weather ahead. This had been previously impossible, as information on trains or horseback could not travel faster than the weather.

Lapham quickly got to work lobbying local officials to help establish an organization to spread information in order to predict the weather, though initially he found little success. Eventually, he partnered with United States Representative Halbert Paine to bring a proposal to Congress. Congress passed the legislation within a week and it was signed by President Ulysses S. Grant on February 9th, 1870. The resolution called for “…taking meteorological observations at the military stations in the interior of the continent and at other points in the States and Territories…and for giving notice on the northern [Great] lakes and on the seacoast by magnetic telegraph and marine signals, of the approach and force of storms.” (US Congress, 1870).

The US Army Signal Corps initially established the weather observation and prediction network eventually known as the Weather Bureau, which evolved into the National Weather Service we know and use today. Operations began on November 1, 1870, with Lapham, himself, making the first forecast of the newly formed U.S Weather Bureau on November 8th, warning of high winds on the Great Lakes. His first forecast was accurate and is credited with protecting lives and saving property of Midwesterners in the Great Lakes region.

By the time of his death in 1875, Increase Lapham had changed the scientific community of Wisconsin. He brought with him an indefatigable spirit of innovation and curiosity, leaving his mark on numerous academic fields and forever changing the landscape of Wisconsin. He is credited as the “Father of the National Weather Service” and proved instrumental in legitimizing the study of weather and the atmosphere as a science. Lapham Peak, the highest point in Waukesha County, is named in his honor, with a dedicated plaque and historical marker standing beside the state park’s observation tower.

Written by Cole Roecker, September 2020.

SOURCES

Martha Bergland, “A Man for All Seasons.” Milwaukee Magazine, September 28, 2009. Accessed on August 9, 2020.https://www.milwaukeemag.com/amanforallseasons/

Glen Conner, History of Weather Observations Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 1837-1948. NOAA’s National Climatic Data Center, 2006.

Rob Nurre, “Increase A. Lapham’s Legacy and the Wisconsin Archeological Society.” WisArch News, v. 11 n. 1, Spring 2011: 5–6.

United States Congress. “House Resolution 839; Recognizing the 150th anniversary of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Weather Service.” Accessed on September 1, 2020. https://www.congress.gov/116/bills/hres839/BILLS-116hres839ih.pdf

The Weather Guys, UW-Madison. “How are the National Weather Service and Wisconsin connected?” Accessed August 8, 2020. https://wxguys.ssec.wisc.edu/2017/11/27/nws/

Wisconsin Historical Society, “Lapham, Increase, 1811-1875; Wisconsin’s First Scientist.” Accessed on August 3, 2020. https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS527

Wisconsin Historical Society, “Historical Site Marker 328: Lapham Peak” Accessed on July 28, 2020. http://www.wisconsinhistoricalmarkers.com/2012/09/marker-328-lapham-peak.html

Wisconsin Historical Society, “19th-Century Immigration and Growth.” Accessed on August 31, 2020. https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS3668

RELATED STORIES

The Works Projects Administration – An Answer to the Great Depression