The End of the Old Fur Trade

The development of fur farms at the close of the 19th century was perhaps the most revolutionary change in North America’s fur industry, and fashion played a significant role in that change. Beaver pelts had been the mainstay of the North American fur trade since the beginning of the 1600s, when the pelts had been used to make men’s hats. Over more than two hundred years, an extensive infrastructure had developed through which both Native American and white trappers harvested pelts for American and international markets.

But by 1900, beaver felt hats had been largely replaced by silk top hats among the fashionable men of Europe. Combined with severe depletion of beaver populations across the continent, this shift in taste caused a collapse of the North American fur industry. Although pelts continued to be used in some clothing like water-resistant coats and the linings of gloves and hats, demand for beaver fur hit an all-time-low in the mid-1800s.

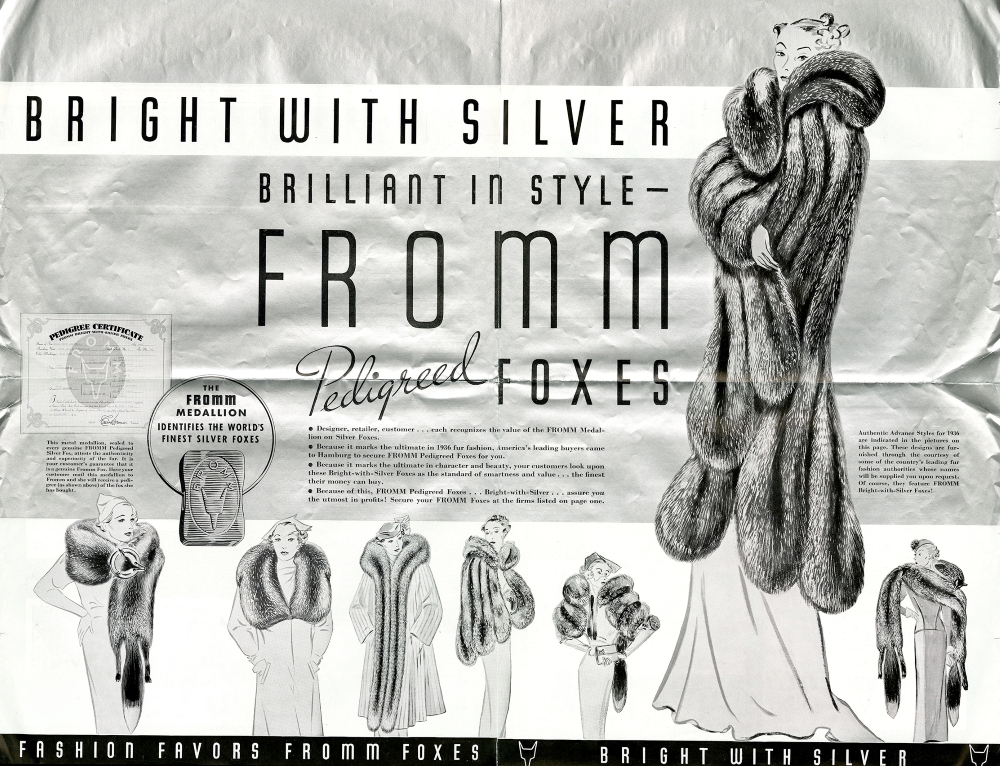

Further developments in fashion, however, ensured that by the end of the 19th Century, fur had begun to make a comeback, but this time in women’s coats instead of men’s hats. The fur linings that had been used to add warmth and comfort inside a coat, now also appeared on coat exteriors to make ever wider collars and cuffs. By the 1920s, fashion houses were sewing fox furs together to create entire jackets, as well as shawls, scarfs, capes and other trendy pieces of clothing.

Fur Farms in the Twentieth Century

In the early years of the 20th Century, a growing number of farmers were applying modern scientific methods to raise foxes for their fur. Raising foxes in captivity made it possible to produce much more fur than ever before. And through careful breeding and by developing proper nutrition, the fur farmers of the early 20th century were able to put out a steady stream of quality pelts that would have been impossible to procure through trapping. Perhaps most importantly, fur farms allowed farmers to carefully breed for color and texture, tailoring their herds to meet the ever-changing demands of fashion. Foxes caught in the wild were predominantly common red foxes, but the controlled environment of a fur farm allowed farmers to breed in genetic traits for “silver” pelts (actually ranging from dark black to pale white) that were rare in the wild and highly valued on the market.

Most fur farms consisted of a few types of different enclosures where fur-bearing animals would be kept throughout their lives. The Fromms developed a three-pen system whereby a fox was first born in the breeding pen of its parents, and then moved to a pup kennel until it was old enough to have its fur graded. If judged to be good breeding stock, the fox would then be moved to its own breeding pen and mated to start the process over with a new litter. If not suitable for breeding, the fox would be sent to a pelting range, where it would grow out its fur before being pelted.

Pelting ranges were often wooded, and designed so that workers could easily feed the herd of hundreds of foxes that resided there. Fur farmers also had to be careful when maintaining large herds of animals to minimize the spread of diseases like distemper. When the time came for pelting, fox keepers employed a range of methods for efficiently killing the foxes, both to make their deaths more humane and speed up the labor. Decomposing bodies could quickly damage the valuable furs so workers had to separate pelts from the dead foxes as soon as possible. Pelts were then treated, sorted, graded, and stored until they could be sent to auction.

Rising demand for fur by clothing makers in the early twentieth century drove an increase in fur farming. The greater supply of fur in turn made such clothing available to a wider range of people. But the changing tastes of fashion continued to have a tremendous impact on fur farmers. In 1934, the fur industry was surprised to find the light silver fox had become the must-have material of the year. A few fur farmers were ready for the shift; the Fromms were a notable example and even managed to upend the industry’s standard auction practices thanks to the demand for their silver furs. But for those fur farmers who had spent decades carefully breeding for dark pelts, it would take years to adjust their herds to produce light silver fur for the market. Successful fur farmers therefore learned to try to anticipate the fashion trends and to maintain a wide range of colors and species of fur-bearing animals to meet the inevitable shifting demands of fickle fashion.

Written by Ben Clark.

SOURCES

Despite being called the “fur trade,” it was really the beaver pelt under the fur that was used to make clothing. The fur was removed altogether. Alice E. Smith, The History of Wisconsin, Volume 1: From Exploration to Statehood (Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1973).

Michael Kronenwetter, Wisconsin Heartland: The Story of Wausau and Marathon County (Midland, Michigan: Pendell Publishing Co., 1984), 41-42.

Dorothy Rae Lewis, “Fur Farming,” Liberty, May 5, 1945. In the 1900’s a good quality red fox pelt sold for around $3.50, while a good silver pelt sold for up to $1,000.

Kathrene Pinkerton, Bright With Silver (New York: William-Sloane Associates, Inc., 1947).

Wisconsin Historical Society, “The Fur Trade Era: 1650s to 1850s,” A Short History of Wisconsin. https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS3585

RELATED STORIES

Canine Distemper and the Fromm Vaccine

The Fromm Brand and the Hamburg Fur Auction

The Fromm Fur Farm