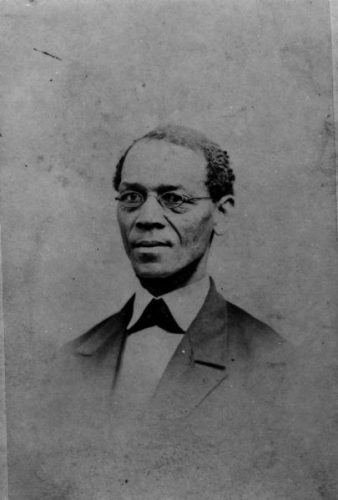

The Wisconsin Idea can be a lofty political goal, and it’s one that the state it is named after hasn’t always lived up to. Like so many other places in the United States, Wisconsin has a history of discriminating against its citizens based on the color of their skin, including denying citizens their right to vote on this basis. This discrimination was directly challenged when one individual in particular, a man named Ezekiel Gillespie, decided to stand up for his right to vote and challenge the system that was preventing him from doing so. Gillespie’s fight demonstrated the ways that even when the state itself didn’t live up to the values entailed in the Wisconsin Idea, individuals could still embody those ideals and make the necessary political changes when the state failed to do the same.

Ezekiel Gillespie was born into slavery in 1818, in Greene County, Tennessee to an enslaved black woman, and was likely fathered by a white slave owner. He bought his freedom from the slave owner as a young man and by 1845 or 1846 was living in Evansville, Indiana with his wife Sophia and eldest daughter Mary. He began working as a self-employed retailer of produce and other small goods but due to the dangers to free black people that the recently passed Fugitive Slave Act posed, Gillespie and his family moved to Milwaukee in 1851. There he set up a permanent grocery store that was quite successful until the economic panic of 1857 when he had to close the store and find work as a messenger for the Milwaukee and St. Paul Railway Company. He had five children with his wife Sophia, but after she died in 1864 Gillespie remained a widower for two years until he remarried Catherine Robinson, who was a widow with two children herself. Ezekiel and Catherine then went on to have four more children together to create a large family, which greatly influenced his community contributions later in his life. With Catherine, who was a devout member of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, Gillespie started the first branch of this church located in Milwaukee. He and his family took a very active role in its organization during the church’s founding years. When Catherine died in 1874, Ezekiel was once again a widower with young children, yet he continued to maintain the familial connections amongst all of his children, even the ones from his first marriage.

Though an 1849 provision of Wisconsin’s constitution extended the right to vote to Black men living in the state, Black citizens continued to be denied the right until 1865. The passing of this provision was unusual in that the state constitution specified that the law would only go into effect if approved by “a majority of all the votes cast” in a state-wide referendum, and though the majority of votes cast were in favor of allowing Black men to vote, more than half of all voters abstained from voting on the issue. Therefore, a majority of votes cast on the issue were in favor of Black suffrage, but the provision did not receive affirming votes from a majority of voters—leaving the provision in a legal gray area. Most believed that the law had not passed and therefore was not enforced. The Wisconsin Legislature passed new suffrage laws in 1857 and 1865, but voters rejected both.

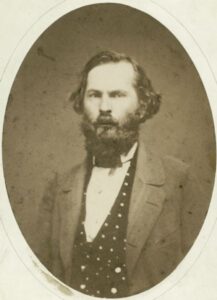

As a leader of Milwaukee’s Black community, Ezekiel Gillespie decided to force action on the issue. Supported by some of the city’s leading abolitionists like Sherman Miller Booth, a newspaper man and editor of The Evening Wisconsin, and former Wisconsin Supreme Court justice Byron Paine, Gillespie attempted to vote in a local election in 1865. When denied from both the voter registration and from the polls, Gillespie filed suit against the Board of Elections contending that though the 1849 provision had in fact received a majority of all votes cast, and was therefore law, Black men were still denied the vote. The case, Gillespie vs. Palmer, quickly made its way to the Wisconsin Supreme Court which unanimously ruled in favor of Gillespie by arguing that it was sufficient to have a majority of only those who actually voted on the referendum in order for it to become law. Thanks to Gillespie’s suit this provision of the Wisconsin constitution was finally recognized as law and had to be enforced as such. His actions officially won black men the right to vote in Wisconsin.

This particular episode of Wisconsin’s history has some interesting implications on the Wisconsin Idea and the values it is supposed to espouse. After all, how can a state claim to be a beacon of progressive politics and democracy while simultaneously denying members of its communities their basic civil and political rights? It seems the answer lies in the fact that the Wisconsin Idea is bigger than Wisconsin itself, and the Idea does not reflect what Wisconsin is but Wisconsin can and should be. The Wisconsin Idea is not meant to serve as a justification for anything the state and its people do, it’s much bigger than that. Indeed, at many points in the state’s history it has failed to live up to those ideals embodied in the Wisconsin Idea. But these failures do not mean that the broader goals of the Idea should be abandoned and by standing against those failures people like Ezekiel Gillespie challenged the state to be true to the ideals it set for itself, to push Wisconsin to embody the Wisconsin Idea, and to consequently reinforce its value to politics.

Written by Maria Serrano, October 2024.

Sources

Christy Clark-Pujara, “Contested: Black Suffrage in Early Wisconsin,” Wisconsin Magazine of History 100(4), Summer 2017. https://content.wisconsinhistory.org/digital/collection/wmh/id/52595

Michael Edmonds and Samantha Snyder, Warriors, Saints and Scoundrels: Brief Portraits of Real People Who Shaped Wisconsin. Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2017.

“First Colored Voter.” The Evening Wisconsin (Milwaukee, WI), June 12, 1897.

John O. Holzhueter, “Ezekiel Gillespie, Lost and Found.” Wisconsin Magazine of History 60, no. 3 (1977): 178-184.

Henry A. Huber, “Citizenship of Wisconsin: Some History of Its Progress.” Racine Times Call (Madison, WI), June 18, 1929.

Supreme Court of the State of Wisconsin, “Gillespie vs. Palmer and others.” Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Supreme Court of the State of Wisconsin. Vol XX. (Madison, Wis.: Atwood & Rublee, 1867); online facsimile at http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/turningpoints/search.asp?id=1377.

Wisconsin Historical Society, “Ezekiel Gillespie: Celebrating Wisconsin Visionaries, Changemakers, and Storytellers.” Celebrating Wisconsin Visionaries, Changemakers, and Storytellers, WHS. https://wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS16501

Wisconsin Historical Society, “Gillespie, Ezekiel (1818-1892), Black Voting Rights Activist.” Historical Essays, WHS. https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS1724

Ideas for Educators:

Click the images at right to view some of the historical documents related to Ezekiel Gillespie and the fight for Black suffrage in Wisconsin.

View more period images and documents related to suffrage and abolition from the Wisconsin Historical Society.

RELATED STORIES

OBJECT HISTORY: John Fox Potter’s “Monster Knife”