The first generation of women—mostly white and middle- or upper-class—to graduate from college in large numbers left school full of promise and enthusiasm, but were largely denied employment in medicine, law, or business. Rejected by the professional world, many focused their energies to combat social injustices instead. Milwaukeean Elizabeth “Lizzie” Black Kander, however, began her social activism long before she attended classes at the University of Wisconsin in Madison.

Lizzie Black Kander was born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin in 1858—the fourth of six children. A rarity of the time, Kander was elected valedictorian of her high school graduating class in 1878. In her speech, titled “When I Become President,” Kander spoke on topics such as the nation’s commerce and tariffs, isolationist policies, political bribery, the ever-widening gap between the rich and the poor, and school reform. The Milwaukee News called her graduation speech the event of the evening.

Lizzie Kander did not become President of the United States, but did become president of the Ladies Relief Sewing Society in 1894, an aid society that shaped her future reform work. Members of the Sewing Society repaired used clothing and donated them to poor immigrant families living in Milwaukee’s Haymarket District, a home for the recent flood of Jewish migrants from Russia. Kander had a different approach, “I am almost sure that this giving for nothing is doing them more harm than good.” She wanted to teach the new immigrants to be bread winners, not alms takers.

Kander’s efforts to aid and acculturate the new Jewish immigrants were not entirely altruistic. A real fear existed within the established Jewish community that the recent wave of mass immigration might provoke anti-Semitic attacks that would not discriminate among native-born Jews of German descent and the new Eastern European immigrants. In her yearly report to the Ladies Sewing Society, Kander stated, “We must try and uplift our downtrodden and unfortunate brethren, not alone for their own sakes and for that of humanity but for the protection and reputation of our own nationality. Their misdeeds reflect directly on us and every one of us individual ought to do all in his power, to help lay the foundation of good citizenship in them.” Kander believed that a social welfare program that stressed Americanization could deter this kind of discrimination and violence.

Although sometimes referred to as “the Jane Addams of Milwaukee,” Kander did not live among her “flock” as Addams did. What made Kander unique from similarly minded reformers was her religious connection to the new immigrants. And while other female social activists of the period used their platform to advocate for national causes like women’s suffrage, temperance, or labor reform, Kander focused her energies on local issues.

Perhaps Kander’s greatest legacy is her work in establishing Milwaukee’s first settlement house and The Settlement Cook Book. Outside of her settlement house work, Kander was a long-time member of the Milwaukee School Board where she helped to establish a high school for girls with a domestic arts curriculum. During World War I, Kander headed the Food Conservation Committee of the Milwaukee County Council of Defense, and during the Great Depression she established one of the first food exchanges in the country. The Lincoln House Food Exchange cooked large quantities of food to be sold at a nominal price. In 1938, she was the first person chosen for the Milwaukee Jewish Center Honor Lecture, and at the 1939 New York World’s Fair she was designated as one of Wisconsin’s outstanding women. Kander died in Milwaukee on July 24, 1940 at the age of eighty-two.

Written by Elizabeth Matelski, May 2017.

RELATED STORIES

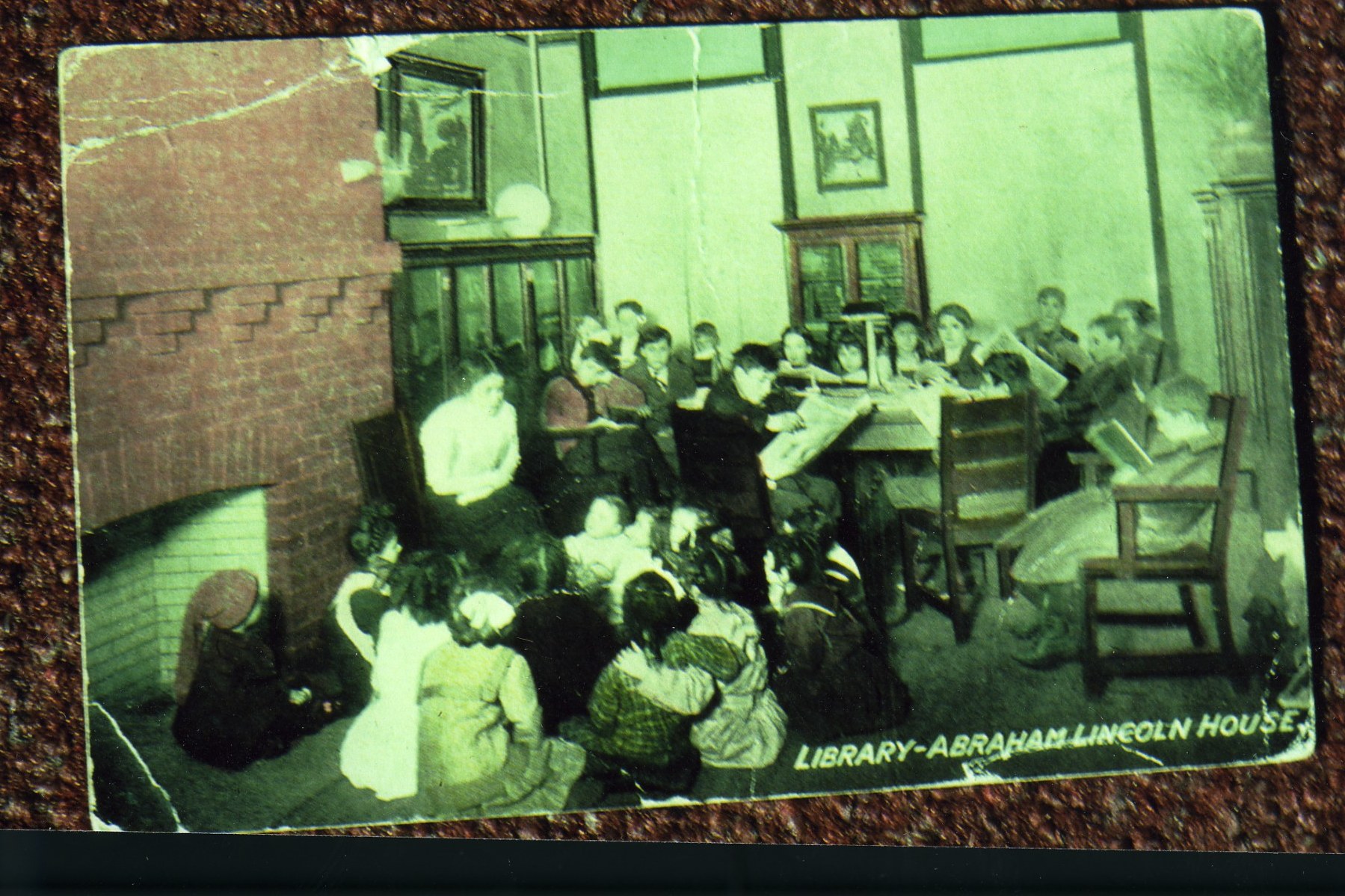

Roots of Milwaukee’s Settlement House

The Settlement

The Settlement House Movement