If you look closely, the landscapes around us tell stories about the past. Sometimes in the curve of a road, a line of trees, or stretch of prairie careful observers can find evidence of the people and animals that used to call a place home. Because people have called Wisconsin home for roughly 12,000 years, in some parts of the state the landscape can tell very old stories. The rocks and cliffs in the Kickapoo Valley, for instance, tell stories about Wisconsin’s ancient as well as recent past.

Sometimes humans change the landscape around them in ways that obscure the stories the land once held. For instance, when the Wisconsin River was dammed to create the La Farge Dam Project, the rising water of the lake threatened to submerge the long history of the Kickapoo Valley beneath its rising water.

Researching the Kickapoo Valley

Hoping to save some of these stories, in the 1950s as part of the proposed dam project at La Farge, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers entered into an agreement with the Wisconsin Historical Society to survey the archeological and historic significance of the lands that would be flooded by the new lake. Beginning in 1959 and continuing through 1974, archeologists from the Wisconsin Historical Society and students from the University of Wisconsin came to the Kickapoo Valley each summer to conduct archeological studies of the lands north of La Farge.

First led by archeologist Donald Brockington and later William Hurley, the studies of the northern Kickapoo Valley provided an amazing catalog of archeological significance. From those initial surveys, a total of 132 archeological sites were identified in the land north of La Farge, and forty of those sites were tested and found to contain significant archeological artifacts. The sites date from between 10,000 BCE and 1,150 CE.

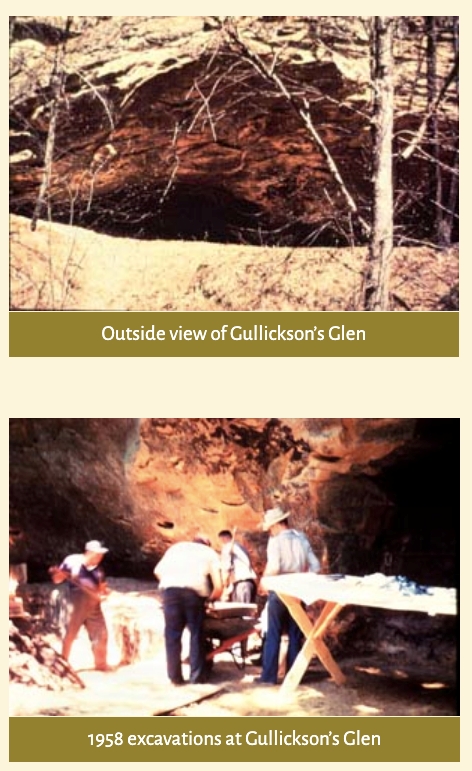

Sixteen of the sites that were tested during those summer surveys were rock shelters. Rock shelters were typically rocky overhangs under which archeologists found evidence of ancient hearths and refuse piles. These rock shelters revealed important information about the diet and culture of Wisconsin’s early inhabitants as well as the ancient flora and fauna of the region. All of the sites that were surveyed yielded artifacts and specimens that were removed and archived in Madison at the State Historical Society.

Archaeology in the Valley

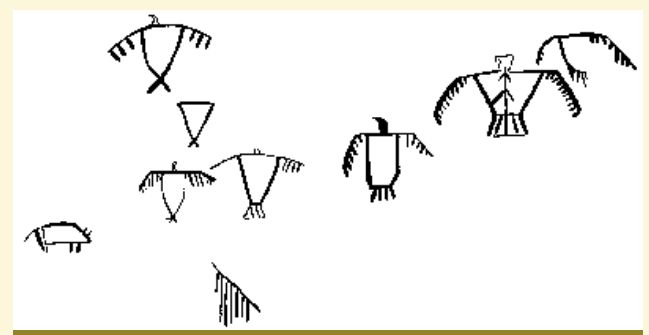

The richness of the archeological finds in the northern Kickapoo Valley in the early 1960s initiated nearly thirty years of continued study in the area. Meanwhile, the dam project which had inspired the surveys was delayed in the 1970s and ‘80s. While the dam project was delayed, the number of significant archeological sites discovered in the Kickapoo Valley grew from the original eight listed in 1959 to a total of 596 by 1998. The sites included ancient campsites and farming areas, linear and conical burial mounds, once-occupied rock shelters and many petroglyphs.

Thanks to these discoveries, the La Farge Dam & Lake Project lands became one of the most intensely studied localities in the region of Wisconsin knowns as the Driftless Area. Nearly half of the sites, 282 to be exact, were of such archeological significance that they are now included on the National Register of Historic Places. The Ho-Chunk Nation is closely connected to the 1,200 acres of the dam project lands. The study of the cultural and historical significance of these lands by the Ho-Chunk people and others continues today.

Geology in the Valley

Another aspect of this intensive research on the dam project lands has been the recognition of the truly unique geologic nature of the northern Kickapoo Valley. In 1974 Wisconsin Senator Gaylord Nelson called for a study to see if the Kickapoo Valley lands could become a national park. In the last Ice Age, glaciers covered most of Wisconsin. Only a small corner of the state escaped the ice. Because this region was not scraped by the glaciers, its geology is very different from the rest of the state and help us understand what Wisconsin was like before the glaciers. The region is known as the “Driftless Area.” Making the case for the Kickapoo Valley to become a national park, Senator Nelson said that the formations located along the river were some of the best examples of the unique geologic features of the Driftless Area that could be found.

The valley did not become a national park, nor did it become a lake. Instead, nearly 6,000 acres of the northern Kickapoo Valley has been designated a National Natural Landmark by the National Park Service. This land, known as the Kickapoo Valley Natural Area, is the third largest natural area in Wisconsin. The beauty of the geologic formations in the Kickapoo Valley as well as the archeological sites are still there for visitors to see – a magnificent discovery for all to enjoy. Paddling down the Kickapoo River we can learn to read the layers of ancient history still present in the Wisconsin landscape.

Written by Brad Steinmetz

Sources

Kickapoo Reserve Management Board, “History,” Kickapoo Valley Reserve (website). http://kvr.state.wi.us/About-Us/History/.

Kickapoo Reserve Management Board, “Archaeological Sites in the Upper Kickapoo Valley,” Kickapoo Valley Reserve (website). http://kvr.state.wi.us/About-Us/History/Archaeology/Archaeology-Sites/

Mississippi Valley Archaeology Center, “Rock Art,” Mississippi Valley Archaeology Center at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse. https://www.uwlax.edu/mvac/past-cultures/specific-sites/rock-art/.

Marcy West, “Citizen Management in a Contested Landscape,” Edge Effects, 5 December 2017. https://edgeeffects.net/kickapoo-valley-reserve/.