Rumored to stalk the Northwoods of Wisconsin, the monstrous Hodag is a legendary creature that has captivated the imaginations of locals and visitors alike. With its fearsome appearance and mysterious origins, the Hodag has become a symbol of folklore and intrigue in the region. Described as a fearsome hybrid between a reptile and a mammal, the Hodag is said to have a spiky back, sharp claws, and menacing horns. The Hodag folklore was born during a period of economic transition for Rhinelander. In the late 1800s, Rhinelander’s attempts to separate themselves from other failed lumber towns may help explain the creation of the Hodag myth.

The origins of the Hodag can be traced back to the late 19th century during a period of unregulated logging in the colonial West. After establishing treaties with the Ojibwe and Menominee tribes, Wisconsin’s logging industry began a boom period in the 1850s. The cutting and distribution of pine trees became the backbone of Wisconsin’s economy, although harvesting the trees was no easy feat. Oxen and horses were used to pull the chopped trees out of dense forests. Long, brutal winters coupled with lumberjack in-fighting, fires, and ice made logging a deadly practice that killed scores of men and oxen. Scarce supplies and wild animal attacks also threatened the livelihood of loggers and their domestic animals. Despite the risks, logging towns like Rhinelander continued to emerge throughout the 1880s.

Despite its initial growth in the mid-1850s, the Wisconsin lumber industry declined in the 1890s. Excessive logging destroyed thousands of acres of forest, leading to significant decreases in timber production and a statewide economic slump exacerbated by a nationwide financial panic in 1893. Sawmills closed and loggers found themselves out of work. Rhinelander’s middle-class population realized that the town could no longer rely on lumber for income and strove to embrace other industries.

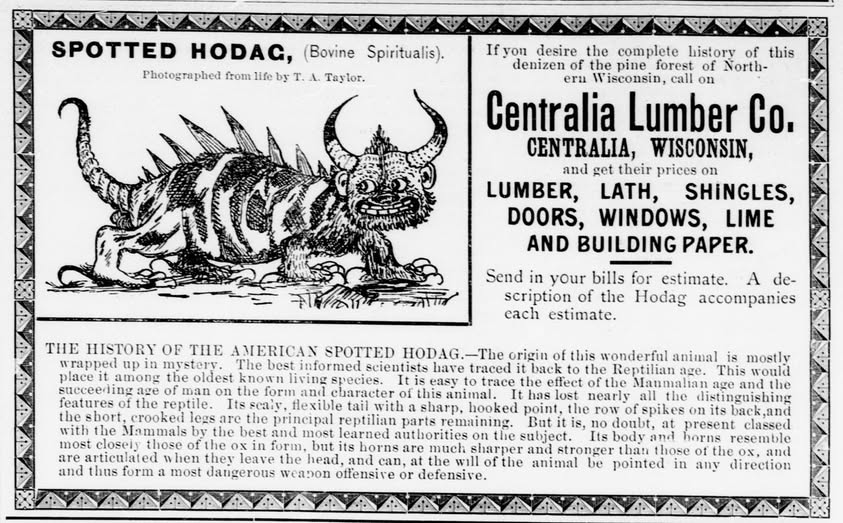

The Hodag story was first reported in 1893 by Eugene Shepard, a well-known prankster and lumberjack from Rhinelander, Wisconsin. Shepard alleged he saw a beast called a Hodag that was as big as a bear with fangs and spikes running down its back. Shepard and a group of lumbermen went into the forest and blew the Hodag up with dynamite, taking a picture of the remains. The photograph was widely circulated, published in the newspaper, and made national news. Three years later, Shepherd claimed to have captured another Hodag, which he displayed at the Oneida County Fair for thousands to view. When scientists from the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C., announced they would be traveling to Rhinelander to inspect Shepard’s Hodag at the fair, the hoax was revealed to be a set of pulleys and wires. However, the Hodag story grew in popularity, less because of a genuine fear of a giant lizard in the woods but more because it became known as the beast who hoodwinked the nation.

Opinions vary as to why the Hodag myth came about. The Hodag can be understood as a community-wide prank that was preserved by national headlines. Shepard claimed that the Hodag was born from the ashes of cremated oxen as an accumulation of animals that had been abused and died at their owners’ hands. One theory is that the Hodag symbolized environmental destruction and animal cruelty, with its depiction as a hybrid creature resulting from humans’ interference with the natural world. Shepard’s myth refers to the mistreatment of oxen who pulled pine trees out of the forests in poor conditions.

However, graduate student Craig Kinnear analyzes a different angle of the Hodag myth arguing that like many other folktales brought about in the logging region during the 20th century, it represents a memorialization of the lumberjack era as the area moved on from the timber industry. To transition into an agricultural society, Rhinelander wanted to put its “wild and wooly” origins behind them by poking fun at its past. Creating folklore and hoaxes around the timber industry allowed the destructive lumber era to remain in the past, surrounded by nostalgia and fond remembrance. Embracing the “quirky, whitewashed working-class culture” turned Rhinelander into a unique and sellable tourist destination, revamping the town’s image.

Written by Sophie Mullen, May 2023.

Sources

Emily Bright, “The Legend of the Hodag.” Wisconsin Life, 19 January 2018. https://wisconsinlife.org/story/the-legend-of-the-hodag/.

Michael Edmonds, Out of the Northwoods: The Many Lives of Paul Bunyan. Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2009.

John A. Gutowski, “The Protofestival: Local Guide to American Folk Behavior.” Journal of the Folklore Institute 15, no. 2 (1978): 113–32.

Lake Shore Kearney, The Hodag and Other Tales of the Logging Camps. Wausau, and Madison, Wisconsin: Democrat Printing Co., 1928.

Craig William Kinnear, The Legend of Logging: Timber Industry Culture and the Rise of Paul Bunyan, 1870-1945. PhD Diss., Notre Dame University. June 2016.

Rhinelander Historical Society, “Hodag Capture Stories.” https://rhinelanderhistoricalsociety.org/article/hodag-capture/