In 1861, a group of Lac du Flambeau Ojibwe traders set up a camp near the South Fork of the Flambeau River in what is now the Chequamegon National Forest. This group was led by Ogimaa Weigiizhig (Chief Big Sky), son of Ah-mous (translated either as Little Bee, or Thunder of Bees), an ambitious and influential leader. There are multiple versions of the story, but Ogimaa Weigiizhig came into possession of an eaglet—by some accounts the group had cut down a tree unaware that there was an eagle’s nest, and Ogimaa Weigiizhig rescued the eaglet; by other accounts he had seen the eagle’s nest, climbed the tree to steal the eaglets, and was made to kill the mature eagle that attacked protecting it’s young; yet another account combines elements of these two stories: Ogimaa Weigiizhig had initially tried to climb the tree to reach the eagle’s nest but was unsuccessful, he decided instead to cut down the tree but only one of the two eaglets survived. In any case, this Ogimaa Weigiizhig came to have the eaglet that would grow to be known as Old Abe.

Continuing down the river on their trading mission, the group came to Jim Falls where they met innkeepers Margaret and Daniel McCann, to whom they traded the eaglet for a bushel of corn. For a few months the eaglet remained with McCanns, who kept it as a pet. The McCann children hunted rodents to keep it fed, and Daniel would play his fiddle for the bird. It’s said that the eaglet seemed to enjoy the music, and whenever McCann would play Bonaparte’s March, the bird would pace to the music during the slower parts, and flap its wings and hop during the livelier parts.

By August 1861, four months after the onset of the Civil War, local men had begun forming volunteer companies for the war effort, but the aftermath of a childhood injury had left McCann with great difficulty walking, so he was unable to enlist.

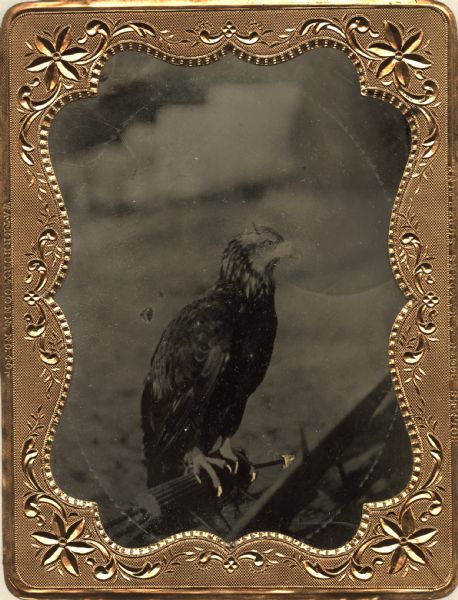

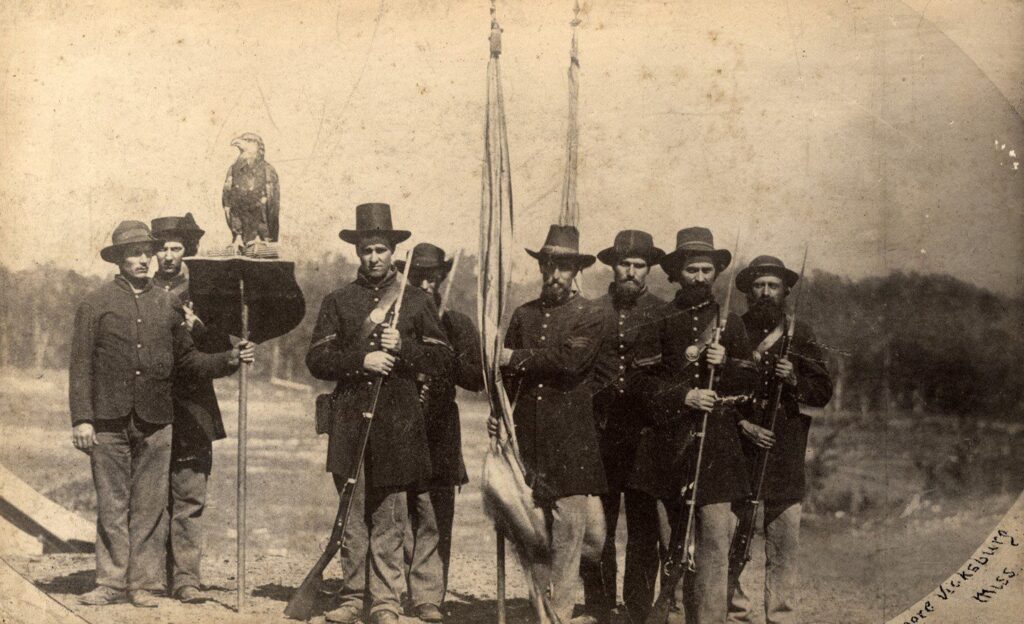

The story goes that McCann was deeply patriotic, and determined to contribute to the war effort; so, he brought the eaglet from his tavern at Jim Falls to offer it as a mascot to the militia company forming there. The reality may have been (at least in part) that he saw an opportunity to unload the rapidly growing bird that he and his children were wholly unprepared to care for. Either way, he first offered the eagle to the Chippewa Falls company, who refused. McCann then offered it to Lt. James McGuire of the Eau Claire company. Again, the story goes that McGuire was initially uninterested, but that his mind was changed when he saw how the bird danced to McCann’s fiddle. Though his infantry unit was nicknamed the Eau Claire Badgers, the idea of a live mascot intrigued the lieutenant, so he approached his unit’s captain for permission to purchase the eagle. It seems that McGuire was not the only one interested in the idea, as he convinced his fellow company men to pool their money to gather the $2.50 McCann had asked. (It’s said that a local merchant, S. Mills Jeffries, reimbursed the men who had initially fronted the money.) The company constructed a shield-shaped wooden perch for the eagle, mounted atop a five-foot pole made to fit into a belt holster, with (at first) a metal chain to serve as tether (this was later replaced by a leather cord).

Soon after, the Eau Claire company trained at Camp Randall in Madison, and mustered as Company C of the 8th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry Regiment. Though they had come to Madison as the Eau Claire Badgers, their live mascot prompted them to change their name to the Eagles. It’s also believed that the eagle was given the name Old Abe while in Madison, in honor of the president.

Fantastic stories of Old Abe’s contributions to the war effort quickly circulated—that Old Abe circled ominously overhead during battles, that he dropped rocks on Confederate soldiers, or that he swooped down to steal their hats, or that his noble screech sent shivers down men’s backs (maybe laughable to anyone who’s ever heard an eagle cry). However, historic records do seem to agree that Old Abe was involved in a recorded 36 battles in Mississippi and Louisiana, and was present at the Surrender of Vicksburg on Independence Day 1863. His handlers wrote that he proved useful on more than one occasion by raising alarm when strangers approached. According to David McClain, Col. Rufus Dawes of the Iron Brigade had once remarked that “Our eagle usually accompanied us on the bloody field, and I heard [Confederate] prisoners say they would have given more to capture the eagle of the Eighth Wisconsin, than to take a whole brigade of men.” (Other sources attribute a similar quotation to Confederate Gen. Sterling Price, who at the Battle of Corinth said, “That bird must be captured or killed at all hazards. I would rather get that eagle than capture a whole brigade or a dozen battle flags!”) To whatever extent, Old Abe was generally a morale booster, a true mascot of the Wisconsin Eighth, and a symbol of Wisconsin pride long after the War.

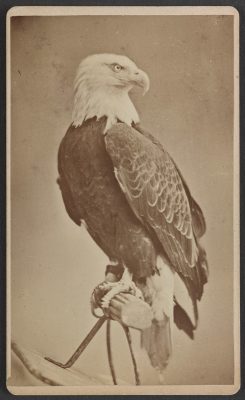

When the Eighth’s enlistment ended in 1864, Old Abe returned with the company to Wisconsin for a well-deserved furlough. It’s said that war aged the bird, but the reality is that the young eaglet they carried from Eau Claire had returned a mature eagle three-years later—with the white head and tail feathers that give the species its name. The Eighth then decided that Old Abe had served his country well, and would not re-enlist.

Following his retirement from service, Old Abe was presented to Governor James T. Lewis, who created the State Eagle Department to care for the animal. Old Abe was given a two-room “apartment” in the State Capitol, with blue-painted ceiling adorned with white stars, as well as a custom bathtub and personal caretaker. For the next seventeen years, Old Abe lived out his days as a celebrity. He attended charity fundraisers, Civil War company reunions, the United States’ Centennial Exposition and World’s Fair in Philadelphia, and made many special appearances at events for the Wisconsin Republican Party. Old Abe met his untimely end, though, after a small fire broke out in the Capitol in February 1881. Though the fire was extinguished quickly, Old Abe inhaled a significant amount of smoke from which he never recovered. He died about a month after the incident in the arms of his final caretaker, George Gilles.

After his death, Civil War veterans from around the state volunteered to serve as pallbearers at Old Abe’s funeral. There was a significant debate about the disposition of his remains, and many championed the idea of interring the eagle at Union Rest, the burial ground within Madison’s Forest Hill Cemetery where the Union soldiers who died while at Camp Randall were interred, as the most appropriate and justified final rest. However, Governor William E. Smith decided to taxidermy Old Abe to preserve his likeness for future generations. The mount of Old Abe was first displayed in a glass case in the Capitol’s rotunda, then in 1885 it was moved to the Capitol’s G.A.R. Memorial Hall where it remained for fifteen years before being moved to the (then newly built) State Historical Society building in 1900. In 1903, pressured by war veterans, Governor Robert M. Lafollette returned Old Abe’s mount to the Capitol. One year later, in 1904, the mount was destroyed in the fire that razed the Capitol.

Since then, a number of feathers said to have been from Old Abe have been found in circulation, and a number of them remain in the State Historical Society. The four most reputable of these feathers came to the state’s collection immediately after the fire: one from Gov. Lafollette, and three other from the wife of a former handler (who had collected feathers shed by the bird.) In 2016, these four feathers were tested to put a long-time rumor to rest: that Old Abe was actually a female bald eagle. According to Eric Lindquist, these rumors may have originated (or at least popularized) by the suffragette Lillie Devereux, who claimed that Old Abe had been seen laying eggs. The DNA tests, performed by UW-Madison’s Biotechnology Center Molecular Archaeology Group concluded that the all four of the feathers were genetically identical and that the gender of the bird that shed all four of the feathers in this collection (sealed since 1904) was male.

Written by Travis Olson, May 2025.

SOURCES

Joseph O. Barrett, History of “Old Abe,” the Live War Eagle of the Eighth Regiment Wisconsin Volunteers. Chicago: Dunlop, Sewell & Spalding, 1865.

Mark Frederick, “The Story of Old Abe,” Wisconsin Magazine of History 2(1), 1918.

Eric Lindquist, “DNA Testing: Famed eagle Old Abe was male,” TCA Regional News, Chicago, 15 July 2016.

David McLain, “The Story of Old Abe.” The Wisconsin Magazine of History, vol. 8, no. 4 (1925): 407-414.

Capt. James A. Page, “The Story of ‘Old Abe,’ famous Wisconsin War Eagle on 101st Airborne Divison patch,” United State Army (website). 15 November 2012. https://www.army.mil/article/91178/the_story_of_old_abe_famous_wisconsin_war_eagle_on_101st_airborne_division_patch

Wisconsin Historical Society, “8th Wisconsin Infantry History: Wisconsin Civil War Regiment,” Wisconsin Historical Society Historical Essay. Accessed July 2025. https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS2026

Wisconsin Historical Society, “How an Indian Chief Captured the Eagle that Became ‘Old Abe’: A Wisconsin Civil War Story,” Wisconsin Historical Society Historical Essay. Accessed July 2025. https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS3221

Wisconsin Historical Society, “‘Old Abe’ the Eagle Accompanies the 8th Wisconsin Infantry into War: A Wisconsin Civil War Story,” Wisconsin Historical Society Historical Essay. Accessed July 2025. https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS3387

Wisconsin Historical Society, “Old Abe, the War Eagle: Civil War Mascot, 8th Wisconsin Infantry,” Wisconsin Historical Society Historical Essay. Accessed July 2025. https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS2541

Wisconsin Veterans Museum, “Famed Bald Eagle Mascot ‘Old Abe’ Confirmed as Male DNA Testing of Mascots Feathers Answers 150 Year Old Debate,” Wisconsin Veterans Museum Press Releases, 14 July 2016. https://wisvetsmuseum.com/famed-bald-eagle-mascot-old-abe-convfirmed-as-male-dna-testing-of-mascots-feathers-answers-150-year-old-debate/

Wisconsin Veterans Museum, “Old Abe Wisconsin’s War Eagle,” Wisconsin Veterans Museum Blog, 20 July 2022. https://wisvetsmuseum.com/old-abe-the-war-eagle/

Richard Zeitlin, Old Abe the War Eagle: A True Story of the Civil War and Reconstruction. Madison: The State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1986.