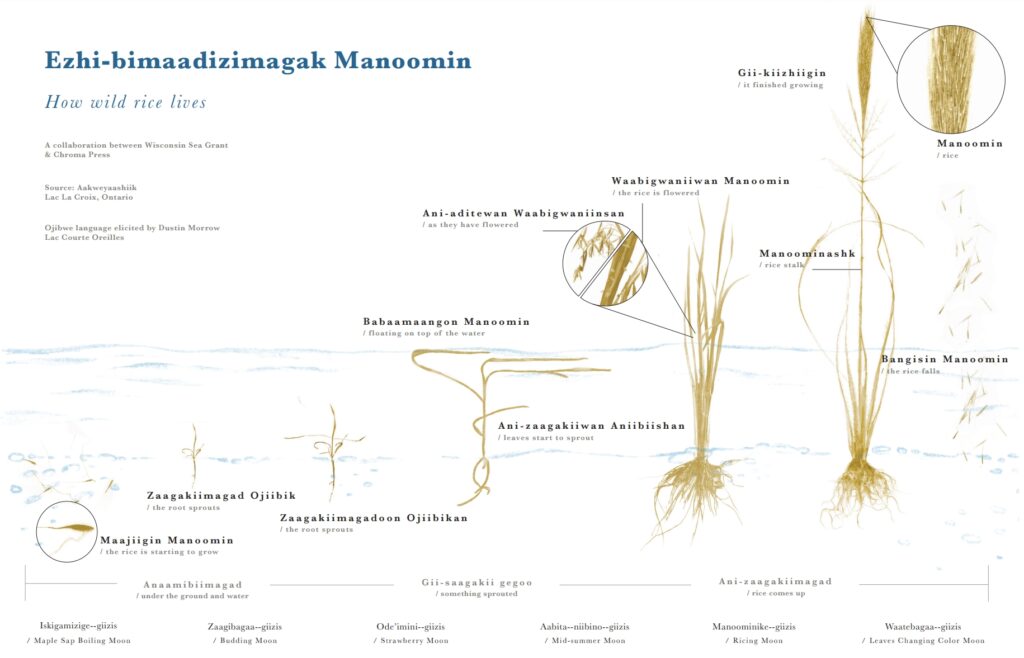

Wild rice grows only in the Great Lakes Region in shallow and calm waters. It requires specific conditions, nutrient-rich muddy soil and stable water levels, in order to properly grow to maturity, to produce the seeds able to be harvested. Damaging the rice stalks or any drastic changes in the water while the rice is growing will not allow the rice seed to mature. The plants reseed for the next year off of the rice that falls into the water and lodges itself into the muddy bottom and a poor harvest one year can lead to issues the next year. Wild rice is significant as a part of Ojibwe people’s diets, but even more so because the rice symbolized this would be Ojibwe people’s home as prophesied. The fragility of wild rice and its importance to Ojibwe people as a reciprocal relationship and promise has led to several ongoing conservation efforts to protect it.

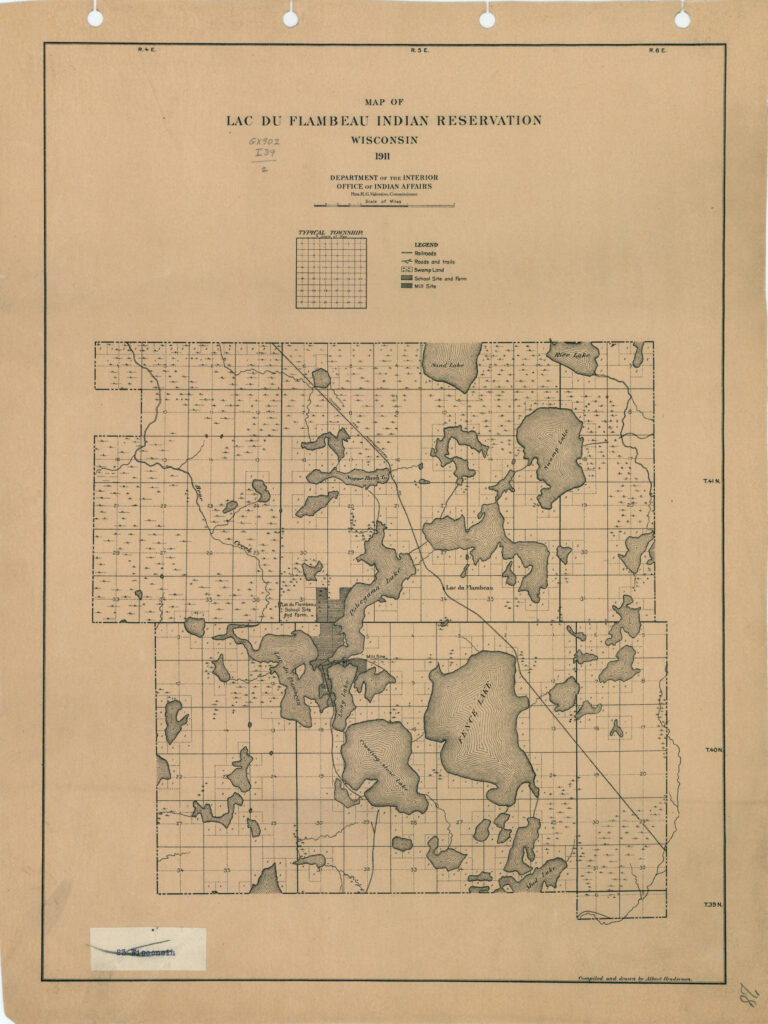

Wild rice faces many challenges to its survival in the twenty-first century that require regulations to be put into place by both tribal and state entities. Maps of the Lac Du Flambeau reservation from 1911 show 225 acres of wild rice in the nearby area, but one hundred years later barely one hundred acres remain in the area. In the 1950s there was a rising demand for wild rice in the public markets. This was great for many wild rice harvesters who could sell their excess for profit, but it also brought in new harvesters who were not Indigenous and did not follow the safe harvesting practices. Many ricing areas were over harvested, plants were being damaged, and companies began unsavory practices in attempts to increase their yield. Recognizing the damages to the rice marshes, the state of Wisconsin, the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission, and individual Indigenous tribes stepped in to regulate ricing practices. The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources instated regulations to ensure that the boats used for ricing could not be longer than seventeen feet and no wider than 38 inches, and required that they only be moved by push pole or paddle. Other regulations mandated that ricing sticks cannot be longer than 38 inches, must be tapered, and are the only tool allowed to be used to gather the rice. Ricing is only allowed from 10 am to sundown and on designated rice lakes, and ricing on tribal property is reserved for only tribal members to rice on. Recently, certain rice spots are only open via notice as tribal and environmental experts step in to monitor wild rice habitat and decide when or if it is safe for harvest. A permit is required so that the number of people ricing can be monitored, and a dealer license is needed if one plans to sell excess wild rice. Limiting the tools and their size protects the rice plants, while limiting the times and areas that can be riced protects future harvests from over-ricing in the current season.

While anyone is able to rice, the permits are meant to dissuade anyone who isn’t looking to properly harvest rice or is only looking for a profit. The permits also allow different programs to monitor how many people are out ricing and where they are going to prevent certain areas from being over harvested for future yields. Wild rice is a way of life and is more significant than a short-term profit to Ojibwe people, and that is recognized through conservation efforts from both state and tribal authorities which work to balance the desire to grow the ricing practice within their communities while continually protecting the rice and allowing it to thrive.

Wild rice is threatened by several different human factors, but reseeding practices are in place to increase the acres of available wild rice. In the mid-1900s wild rice was being harvested commercially, but the demand was higher than what the harvest would allow for. To combat the desire for more rice and the increasing regulations, companies developed paddy rice that was similar to wild rice but grown in a farm setting rather than naturally. The rice was slightly different as it was altered to be hardier, be able to grow elsewhere, and produce larger amounts. Paddy rice is now a threat to wild rice as the seeds can spread to wild rice areas outcompeting the natural rice that exists there, and jeopardizing the future harvests of rice. Work is being done to reseed wild rice with its own seeds so that it is plentiful enough to resist paddy rice. Tribal experts monitor rice beds and decide what areas need the most assistance in reseeding. Wild rice that is collected is thrown back into the water for it to settle at the bottom and grow the next year. This means a smaller harvest, but it sustains the rice and hopefully means a healthier rice bed and larger harvest the next year. Ojibwe people understand that just because the rice was promised to sustain them, that does not give them the right to over use the rice and not put in the efforts to sustain the rice back.

Education is a large part of the conservation efforts for wild rice in Wisconsin. Many residents of the state do not know that wild rice grows here, or do not understand the significance of it to Indigenous peoples. Irresponsible or unaware watercraft owners are a threat to wild rice at any stage of the plant’s growth. Wild rice is extremely fragile in its early stages of growth and the wake from boats or small watercraft can break the plants before they mature. Disturbing the water can move the bottom and disturb the seeds that are either attempting to grow or resettle on the bottom and can prevent a fertile harvest the next year.

There are stories of people finding the shallow waters of ricing areas to be optimal for jet ski stunts, but the commotion caused by this severely affects the plants. Education about wild rice, its growth patterns, and the specific areas that are protected is one way to combat this. Signs and buoys that designate “no wake” areas are placed near rice beds to alert people to change their boating habits in those areas. Through the use of social media more is being shared about wild rice in ways that can reach broader audiences who might be able to make an impact with their decisions. In 2024, the Bad River band released a film about their history (right), the significance wild rice holds, and the issues they have seen, as well as the ways they have found to help. Education also plays a large part in politics as people in positions of power to alter access to certain areas, place signs, set penalties for damaging the rice, and make this a well-known issue, are learning about wild rice and what they can do to help. Ojibwe people have always been good stewards to the rice that made this their home, and an important conservation effort is sharing that knowledge with others to do the same.

The largest current threat to wild rice is climate change, but Ojibwe people and non-Indigenous partners are constantly working to find more sustainable ways to live that will protect the rice. Fish hatcheries are often located near rice beds to not only maintain a healthy fish population, but for the spawn to provide the nutrients that the soil needs in order for rice to grow well. Tribal run fish hatcheries are a way of looking after the earth and returning what has been taken.

Wild rice is also a very particular plant whose growing conditions are greatly affected by the change in climate. Warmer temperatures can lead to droughts and sudden heavy rainfalls that destabilize the water levels around rice beds. Severe storms are likely to damage plants, lead to flooding that kills the plant, or wash out the bottom and eliminate future harvests. Even temperatures in the winter affect the plants, as they need the harsh cold of the Midwestern region to generate thicker lake ice that insulates the seeds along the bottom. Milder winter temperatures result in fewer healthy seeds. There is little that can be done to immediately protect the rice from floods that appear, or the gradual increase in temperature, but research is being conducted for the future. Researching ways to live on the Great Lakes sustainably and reduce the impact of climate change is the number one priority. This includes things that people who live along the lakes can individually do to reduce their impact, but also ways that corporations can continue their business while not damaging the lakes’ resources. Several tribes are involved in larger efforts that focus on sustainable living to ensure there is still rice for generations to come.

Ojibwe tribes are also working to protect wild rice legally by combating larger companies in court who pose a risk to, or are harming wild rice areas. Industries encroach closer to protected spaces in ways that may seem small to them, but can cause lasting damages to wild rice plants. Oil pipelines are one of these industrial threats to wild rice as improperly maintained pipes cause oil to seep into the surrounding soil. With expansive pipelines that run through remote locations, many argue that the question is not if, but when something will go wrong with one of the pipelines. Enbridge Line 5 is specifically an oil pipeline that runs through the Bad River reservation and intersects several streams and rivers that lead to Lake Superior and the ricing beds. A leak would damage the rice for a few harvests, but a rupture of the pipe could be catastrophic as it would potentially kill all of the rice plants and seeds, preventing future growth of a plant that is already so threatened. The Bad River Tribe is involved in a current legal battle with Endbridge to remove the pipeline from privately owned lands on the reservation where it is in a state of trespass. Enbridge is a multi-million dollar company with an extensive legal team, but with the future of wild rice on the line, Bad River refuses to back down. Wisconsin courts ruled that Enbridge has until 2026 to remove the pipeline from the areas it is trespassing in, but Enbridge refuses, has filed several motions against the ruling, and is continuing the battle in court. Mines near water sources connected to rice lakes are also of special interest as the chemical runoff can destabilize ecosystems and make it impossible for wild rice to grow. Legal cases and political protests to end mining operations near wild rice beds have also been prevalent in Madison courts. Ojibwe people conserve wild rice through every possible way, including the legal system as it is often the only way to make large corporations pay attention.

Wild rice is an important food source and promise to the Ojibwe people that this area will always be their home. As a part of that promise, they look after the rice so that it will continue to remain true for generations to come. There are several conservation efforts to maintain the rice and bring it back to its full harvest potential including: new regulations, reseeding practices, education, research and a focus on sustainable living, and legal battles. Each of these approaches works to protect, spread awareness, and replenish wild rice in different ways so that in seven generations there won’t be the fear of losing wild rice.

Written by Kyra Michalski, November 2024.

Sources

Barb Bell and Ethel Plucinski, Ethel. “That was Quite an Adventure!” News from the Sloughs (Odanah, Wisc.) October 1, 1997.

Danielle Kaeding, “Wild Rice Harvest Tradition Passed Down to Youth,” Wisconsin Life, Wisconsin Public Radio. October 9, 2019. https://wisconsinlife.org/story/wild-rice-harvest-tradition-passed-down-to-youth/

Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission, “Manoomin-Wild Rice: The Good Berry,” Pamphlet. https://glifwc.org/publications/pdf/Goodberry_Brochure.pdf

Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission, “Ricing with Tommy Sky: A Sequel to Growing Up Ojibwe,” Mazina’igan, 2007. https://glifwc.org/publications/pdf/Ricing_Supplement.pdf

Mackenzie Martin, “Birch Bark Canoes Take Time, As Does Learning We’re Stronger Together,” Wisconsin Life, Wisconsin Public Radio. December 7, 2021. https://wisconsinlife.org/story/birchbark-canoes-take-time-as-does-learning-were-stronger-together/

University of Wisconsin-Madison, Center for the Study of Upper Midwestern Cultures, “Wiigwaasi-Jiimaan,” Site accessed November 2024. https://canoe.csumc.wisc.edu/index.html

“Wild Rice Festival Celebrates Harvest,” WXPR. September 11, 2014. Accessed August 2024. https://www.wxpr.org/arts-life/2014-09-11/wild-rice-festival-celebrates-harvest

Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, “Wild Rice Harvesting,” Accessed August 2024. https://dnr.wisconsin.gov/topic/wildlifehabitat/rice.html

Wisconsin PBS Education, “The Ways: Manoomin, Food that Grows on Water,” https://pbswisconsineducation.org/story/manoomin/

Moka’aangiizisiban Tribal Museum

Research for this object and its related stories was supported by the Moka’aangiizisiban Tribal Museum, which operates under the Mashkiiziibii Natural Resources Department, and the Bad River Tribal Historic Preservation Office. Visit their website to plan your visit!