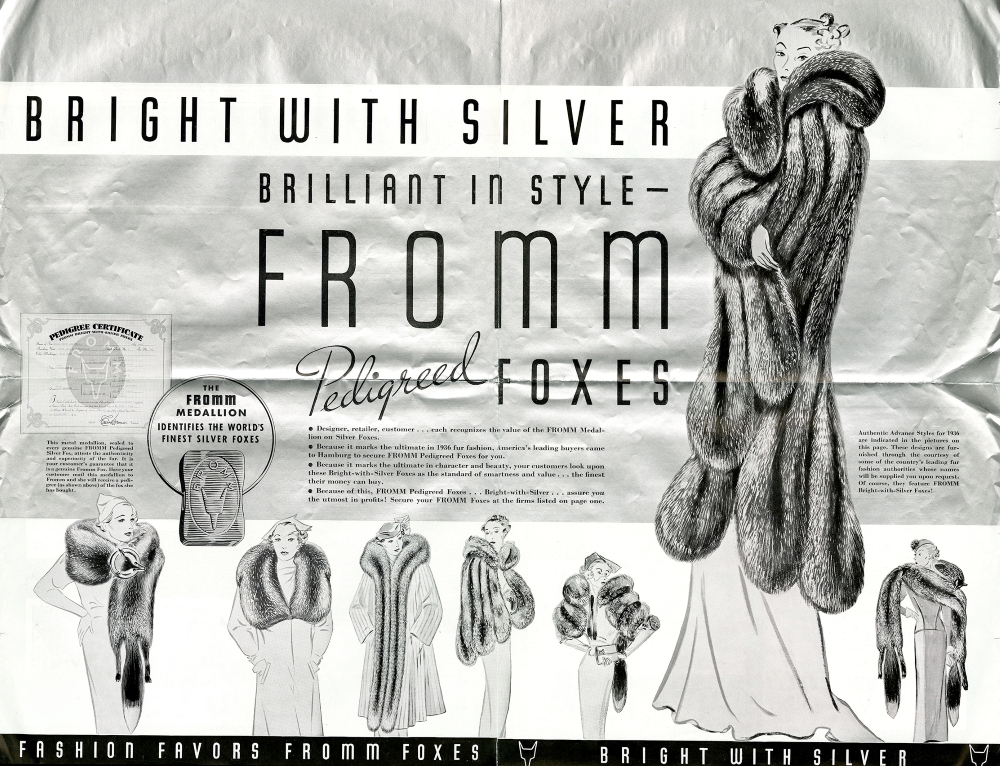

Probably the biggest reason for the success of the Fromm Brothers’ fur farm was the particular color of fur that they bred. As fashions shifted to favor the trademark Fromm “bright with silver” color, the Fromms were in a position to capitalize on their control of light silver fox fur supply. They then used their resulting fame to shape the international fur trade by getting into the business of auctions, where fur producers and buyers met.

The pelt of the silver fox can actually be any color ranging from a dark black to bright white, depending on the ways farmers breed their foxes. Darker black-haired pelts had been the most sought-after furs in the 1910s and 1920s, leaving the Fromms, with their preference for the lightest colored silver foxes, in the minority at that time.

But in 1934, scarves, wraps, and coats generously trimmed with bright silver fur suddenly became very popular. The Fromms had noticed some promising changes in the prices for silver fur in the 1920s, and in 1928 they started an advertising campaign aimed at spreading the Fromm brand to prospective buyers. Most other fur farmers were caught off guard, and had to scramble to switch their fox breeding to produce lighter coats. Because the breeding process is slow, however, it would take years before these farmers could adjust to meet current trends. Way ahead of their competitors, the Fromms had cornered the market and, in the mid-1930s, were sitting on the largest supply of light silver foxes in North America.

The Fromms made the most of their newly found influence to reshape the industry. The brothers had long complained alongside other fur farmers, about the unfair tradition of holding fur auctions in centers of trade like Leipzig, London, Paris, St. Louis, and New York—all far from the place where furs were raised. Farmers had no say or influence over prices once they shipped their harvest off on trains to the auctions. And so the Fromms decided to change things by inviting the fur buyers directly to their Hamburg, Wisconsin, farm to bid on Fromm furs directly.

The greatest supply of silver fur in the world, set amidst the rustic, wintry forests of central Wisconsin, attracted fur buyers in droves. At the first Hamburg auction in 1935, there were 86 clothing companies from cities across the United States. They even chartered a train to run nonstop from New York’s Central Station to Wausau, Wisconsin, to accommodate all of the buyers from that region.

The auction was a success for everyone involved. The buyers had direct access to the largest supply of silver foxes in the world, while the Fromms sold their entire stock—a first in fur auction history—of 7,500 pelts at an average of 15% over what they had sold for in New York the previous season. At one point a single pelt was sold for $450—the single highest price paid for a pelt since the dawn of the Great Depression—at which point the gathered buyers “stood and cheered.” As they left, the visiting buyers made a point of asking to return to attend the auctions next year. The Fromms obliged, making their auction a regular event. Indeed, for the next few years they hosted three events annually (autumn, mid-winter, and spring) that continued bringing in record prices for furs, including non-Fromm furs from other Wisconsin farms.

By the end of the 1930s, however, the novelty of the Hamburg fur “resort” had worn off. Competitors had eroded the Fromms’ near-monopoly over silver fox fur and, as fur prices fell due to greater supply, the family’s Wisconsin auctions stopped being profitable. As fur prices fell in the 1940s, the Fromms relocated their auction company (Federal Furs) to New York, which had become the global fur capital while London and Paris languished during WWII. But for several years at least, the Fromm brothers’ silver-colored foxes had allowed a small farm in rural Wisconsin to dominate the international fur trade.

Written by Ben Clark.

SOURCES

J.C. Furnas, “Hide and Hair DeLuxe,” The Saturday Evening Post, January 25, 1941.

Michael Kronenwetter, Wisconsin Heartland: The Story of Wausau and Marathon County (Midland, Michigan: Pendell Publishing Co., 1984), 41-42.

Dorothy Rae Lewis, “Fur Farming,” Liberty, May 5, 1945. In the 1900’s a good quality red fox pelt sold for around $3.50, while a good silver pelt sold for up to $1,000.

Kathrene Pinkerton, Bright With Silver (New York: William-Sloane Associates, Inc., 1947). The furs went for an average of $75, or roughly $1,320 today adjusted for inflation.

Melvin N. Taylor, “Ten-Million-Dollar Fox Tale,” The Saturday Evening Post (February 13, 1937).