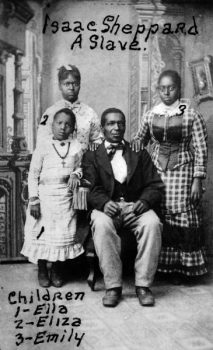

It may come as a surprise to learn that during the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries slavery existed in the region that would become the state of Wisconsin. Over this period, thousands of enslaved African Americans or enslaved American Indians lived and worked in this region. Although their lives and histories have been obscured, enslaved men and women helped build some of the most important industries in the state.

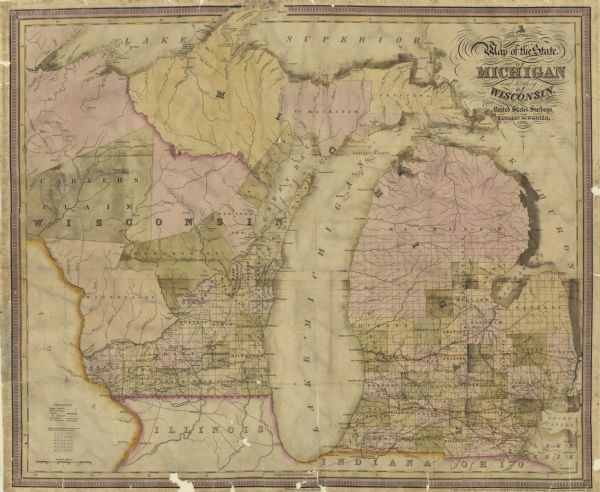

French fur traders were the first to introduce chattel slavery to the region. They brought hundreds of enslaved African Americans and Kaskaskias, Meskwaki, Pawnee, and others into the region from the 1670s to 1763. When the British took control after the French and Indian War (1754-63), over 100 enslaved African Americans entered what would become the state of Wisconsin against their will. These men and women were brought to this region as laborers supporting the British fur trade. After the Revolutionary War, the newly formed United States drafted the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 to govern the territories on the frontier of the new country, including the lands that would become Wisconsin. The Northwest Ordinance forbade the owning of slaves, but lax enforcement permitted slavery to continue in the region.

Chattel slavery increased during the Lead Rush in the Upper Mississippi River Valley, supporting an economic boom in southwest Wisconsin and neighboring parts of Iowa and Illinois. Because the Northwest Ordinance stipulated that statehood was dependent on population, the population spike associated with the lead rush helped transform Wisconsin into a territory and then a state by 1848.

Prominent figures in Wisconsin history were connected to this history of slavery and lead mining. Henry Dodge (Dodgeville), John Rountree (Platteville) and George W. Jones (Sinsinawa) all came to the region in the 1820s to mine and process lead. Each brought enslaved individuals with them from Missouri or Kentucky.

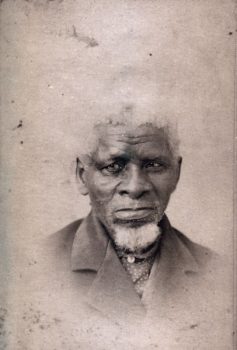

In the case of Henry Dodge, he arrived in the Wisconsin Territory in 1827 from Missouri and brought five enslaved individuals with him. Toby, Tom, Lear, Jim, and Joe were held in bondage in the Wisconsin Territory, working as smelters at Dodge’s furnace. Dodge had promised to free the five men if they would work a short time at his smelting furnace. Instead, Dodge held them in captivity for twelve years despite the prohibition of slaveholding in the region. The five individuals were finally freed on April 11, 1838. The lead industry was already in decline when slavery was abolished in the United States in 1865.

Of the approximately 100 African Americans who worked with lead in nineteenth-century Wisconsin, most gained their freedom by 1842. Toby, Tom, Lear, Jim and Joe remained to work in the lead industry for years beyond 1838 as free Wisconsinites soon to be joined by freemen like James D. Williams. By 1860, the African American population in Wisconsin had grown to 1,200, all of whom were free.

Written by Winifred V. Redfearn and Deja M. Roberson.

SOURCES

Grant County Historical Society, “Pleasant Ridge: A Refuge for Former Slaves,” https://grantcountyhistory.org/pleasant-ridge-a-refuge-for-former-slaves/

Eugene R.H. Tesdahl, “Lead, Slavery, and Black Personhood in Wisconsin,” The Wisconsin Magazine of History 102(4), Summer 2019, 17-27. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26683202

Eugene R.H. Tesdahl, et al. “African American Lead Miners in Wisconsin,” The Mining and Rollo Jamison Museums, Platteville, Wisconsin, online exhibit. https://mining.jamison.museum/african-americans-in-the-lead-mining-district/

Wisconsin Historical Society, “Pleasant Ridge: A Community of Black Farmers in Wisconsin,” Historical Essay. https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS1576.