By 1890, the majority of Milwaukee’s Russian and Polish Jews lived in the city’s Second Ward, also known as the Haymarket District. Lizzie Black Kander worked as a truancy officer from 1890 to 1893, which gave her a front-row view of conditions in the impoverished Haymarket District. She reported, “there is no location in the city where the property is so cheap, rents so high, and accommodations so poor. Old buildings that were originally designed for one family are inhabited by many. Upstairs, downstairs, and damp, dark basements are divided and subdivided into apartments, with very little alterations.” She described the tenements as “a deplorable situation, threatening the moral and physical health of the people.”

By 1894, Kander became the president of the Ladies Relief Sewing Society, an aid society that collected, mended, and provided clothing for needy families. Kander’s involvement in the Sewing Society became the foundation for her future activism and the blueprint for Milwaukee’s first settlement house.

In 1895, the Sewing Society became the Keep Clean Mission. Activities were held once a week in the basement of Temple B’ne Jeshurun—games, entertainment, and craft lessons to spread the gospel of cleanliness. Kander believed that good hygiene was the first step in elevating the new Jewish immigrants. In 1896, the organization’s name changed again to the Milwaukee Jewish Mission to better represent the variety of services they provided.

Cooking classes were introduced in 1898, a class of 18 girls all between the ages of 12 and 14. The cooking school quickly earned the reputation for being the only kosher cooking class outside on New York City. Instruction had to observe kosher practices to attract the Russian Orthodox students.

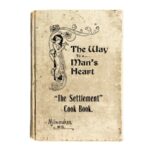

From the start, the cooking classes had been as popular as the sewing school. Although the sewing school strove to train professionals, the cooking school did not seek to professionalize its cooks. Instead, Kander focused on training “future mothers” to prepare a wide variety of nutritional meals on a budget—by giving her classes a copy of The Settlement Cook Book, Kander helped these mothers achieve these goals. Her classes also focused on housekeeping, cleanliness, and setting the table and serving meals properly.

Cuisine connects heavily with culture, and settlement house workers believed that immigrants’ eating habits demonstrated clear markers of cultural identity that had to be replaced for assimilation to occur. Kander recognized that the women in her classes could not prepare middle-class meals—they would not have the money. Instead, she taught her students to be spendthrift while still elevating their gentility. Kander believed these skills were just as essential for building “moral character.” The efforts of Kander and others at the Settlement House helped acculturate the new immigrants who found their way to Milwaukee.

Written by Elizabeth Matelski, May 2017.

SOURCES

Noa Gutow-Ellis, “Cookbooks from the Collection,” Museum of Jewish Heritage. 19 May 2020. https://mjhnyc.org/blog/cookbooks-from-the-collection/

Angela Fritz, “Lizzie Black Kander,” Encyclopedia of Milwaukee. https://emke.uwm.edu/entry/lizzie-black-kander/

Angela I. Fritz, “Lizzie Black Kander and Culinary Reform in Milwaukee, 1880-1920,” Wisconsin Magazine of History 87(3), Spring 2004, 36-49.

Ruth Harman and Charlotte Lekachman, “The Jacobs’ House,” Wisconsin Magazine of History 16(3), March 1933, 252-84.

Mrs. Simon (Lizzie Black) Kander, The Story of the Abraham Lincoln House. Milwaukee: The Settlement at the Abraham Lincoln House, 1903.

Bob Kann, A Recipe for Success: Lizzie Kander and Her Cookbook. Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2007.

Genevieve McBride, On Wisconsin Women: Working for their Rights from Settlement to Suffrage. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1993.

Winifred Salisbury, “Letters from the Settlement House,” Milwaukee History 19(2), 54-68.

Louis J. Swichkow and Lloyd P. Gartner, The History of Jews in Milwaukee. Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1963.

Fielding Utz, “Northcott Neighborhood House,” Milwaukee History 6, Winter 1983, 115-124.