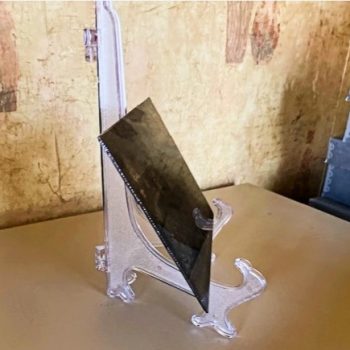

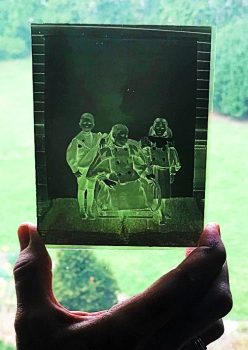

Kodachrome? Fujifilm? Ektachrome? All too modern! We’re stepping back more than a century to an era when photographers used glass plates – not film – to capture an image.

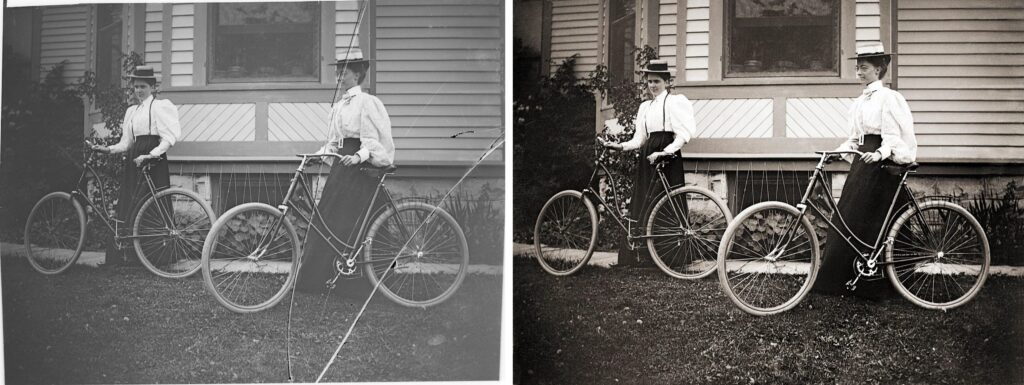

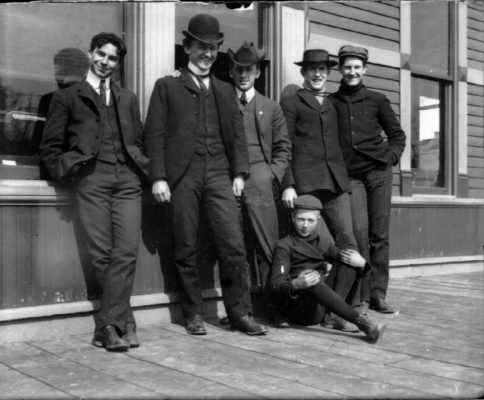

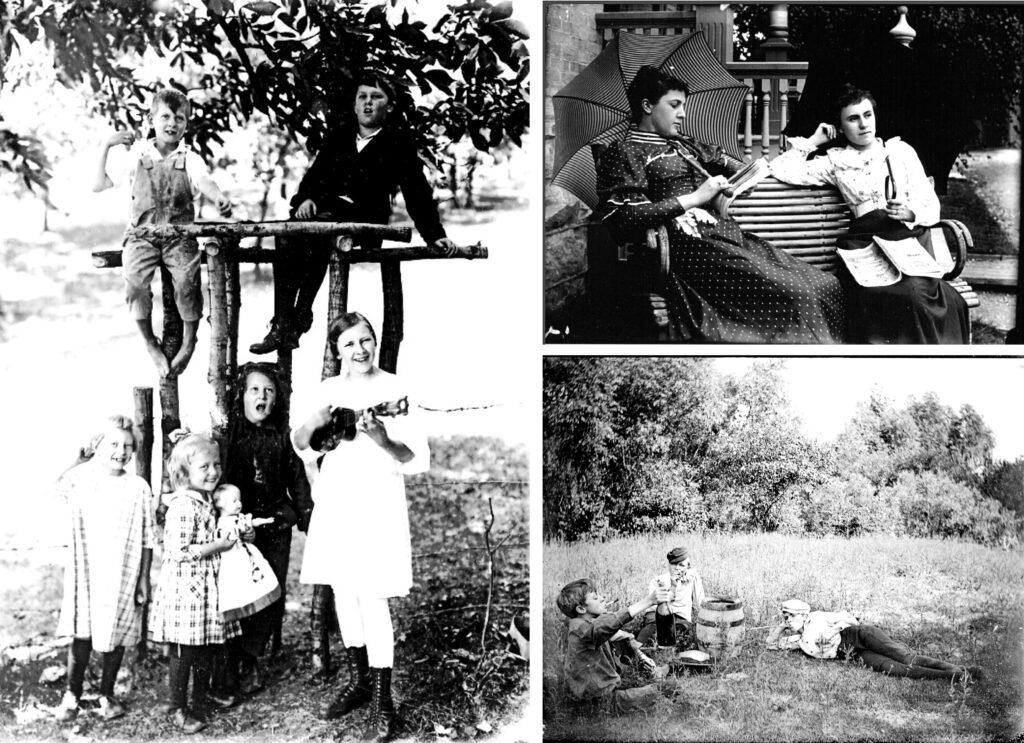

Kodachrome? Fujifilm? Ektachrome? All too modern! We’re stepping back more than a century to an era when photographers used glass plates – not film – to capture an image. The Wauwatosa Historical Society houses an extraordinary collection of over 2,000 glass plate negatives documenting the Lefeber family at the beginning of the 20th century.

In 1886, three brothers – James, Abraham, and Joseph Lefeber – opened a general store in the heart of the Wauwatosa village at the corner of State Street and Harwood Avenue. After the brothers retired, James’ three sons – Ernest, James C., and Cornelius – managed the business. The Lefeber Brothers’ Department Store prospered until 1958 when it closed due to competition from chain stores and a nearby shopping mall. Cornelius Lefeber and his father, James, were the photographers who created the glass plate negatives.

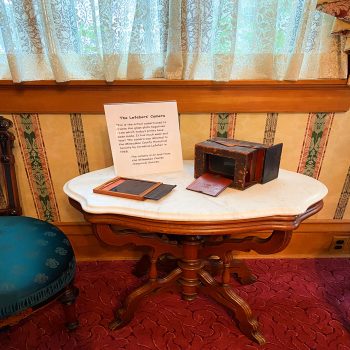

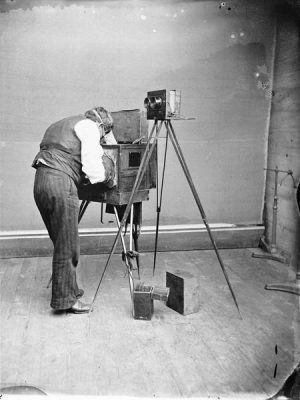

Before photographers had rolls of film, they used thin glass plates inserted into the back of a bellows camera. These glass plates were coated in photosensitive chemicals that would record an image when exposed to the light entering through the camera’s lens when the photographer opened the camera’s shutter. The light reacted with the chemicals and created a photo negative on the thin pane of glass. The bellows (the flexible, accordion-like structure at the camera’s center) could be expanded or contracted to allow the photographer to capture a close-up or far-away image.

There are two kinds of glass plate negatives, wet and dry. Wet (or wet collodion) plates were invented in 1851 by English photographer Frederick Scott Archer. This process involved the photographer preparing a transparent glass plate with cellulose nitrate and ether, then soaking it in silver nitrate to create a photosensitive layer, then loading it into the camera. The process was messy, and the photographer had to work quickly. Also, the image had to be developed rapidly – usually within five or ten minutes.

Well-known Wisconsin photographer H.H. Bennett used wet collodion glass plates to capture many of his beautiful images of the Wisconsin Dells; his photographs, distributed nationally, contributed significantly to the growth of tourism in the region. Photographers like Bennett had to transport an unwieldy load into the field, including a camera, a tripod, fragile glass plates, toxic chemicals, and (because the negatives needed to be developed so quickly) a portable darkroom.

In 1871, the invention of dry (or gelatin dry) plates by an English physician and photographer, Richard Leach Maddox, revolutionized the world of photography. Maddox knew the ether on the wet plates was dangerous to people’s health, so he experimented with different chemicals. Maddox used silver bromide and gelatin to coat the plates, noting that when the mixture dried, the plate could be stored for months and used whenever convenient. By the time James and Cornelius Lefeber used these dry plates, they were being produced in factories – for example, Eastman-Kodak in Rochester, New York. (George Eastman was the first to patent a coating machine to manufacture dry plates in 1880).

Gelatin dry plate negatives were used widely from the 1880s until the late 1920s. In addition to Wauwatosa’s Lefebers, other amateur photographers captured images of people and events in their Wisconsin communities. Some examples of their collections, available for online viewing, include the photos of F.S. Eberhart, who focused on the Sauk Prairie area, the Jones-Kreitzman images of Watertown, and Roley Troxel’s photographs that record the area surrounding Prairie du Chien.

Glass plate negatives provide an excellent range of detail, especially when scanned at high resolution. A digital scanner can convert a negative glass plate to a positive image that can be printed or shared online for viewing. The process is part of a project launched by the Wauwatosa Historical Society’s Research Library volunteers.

–Written by Carol Rosen, January 2024.

Sources

David Lindsay and Reese Jenkins “George Eastman: The Wizard of Photography,” American Experience, PBS Wisconsin. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/george-eastman/

Digital Public Library of America. In Focus: The Evolution of the Personal Camera. Digital Exhibition. https://dp.la/exhibitions/evolution-personal-camera/early-photography

Getty Museum. “The Wet Collodion Process.” YouTube, uploaded by The Getty Museum, 17 November 2010, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiAhPIUno1o

Jones-Kreitzman Family Collection. Watertown Historical Society (Watertown, Wisconsin). Viewed online at http://www.watertownhistory.org/articles/Jones_-_Kreitzman_Family_Collection.htm

Lefeber Glass Plate Collection, Wauwatosa Historical Society (Wauwatosa, Wisconsin)

PBS Wisconsin, “Sauk Prairie: Glass Plates,” Wisconsin Hometown Stories. https://www.pbs.org/video/sauk-prairie-glass-plates-nu1pku/

R. W. Troxel Glass Plate Negative Collection, University of Wisconsin–La Crosse. Viewed online at Murphy Library Digital Collections, https://digitalcollections.uwlax.edu/jsp/RcWebBrowse.jsp or Recollection Wisconsin, https://recollectionwisconsin.org/collections/r-w-troxel-glass-plate-negative-collection

RELATED STORIES

Wauwatosa’s Lefeber Brothers Department Store

Images of a Treasured Childhood: At Home in Wauwatosa with the Lefebers