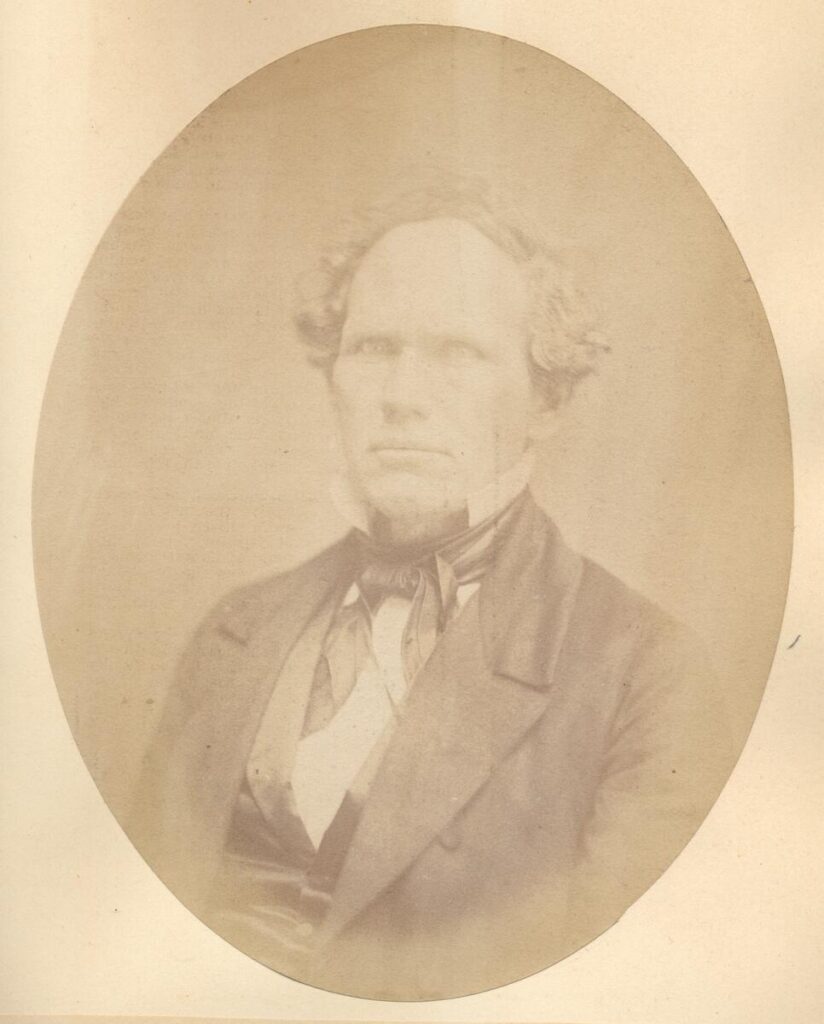

By many measures, John H. Rountree fit the archetype of a successful 19th century American pioneer. Born in 1805 in Kentucky, he made his fortune staking a claim near the Platte River in the then lucrative lead mining region of southwestern Wisconsin, there he founded the town of Platteville which he built around his smelting furnace likely the first built in the region. He reveled in the martial prestige that came from fighting Native Americans. He would serve in many roles in Wisconsin government, both when it was a territory and when it was a state. As one enthused biographer wrote in the Platteville Witness in 1934, “Mr. Rountree had a part not only in laying the foundations of our commonwealth and our state institutions, but it was his privilege to behold these developed into a life that promises permanency…The touch of his hand is traceable upon all the institutions that we as a people love.” Another biographer writing about Rountree in 1875 remarked that he “can look back to the days when Wisconsin was an uninhabited wilderness without roads, bridges or any conveniences for transportation, and contrast the former days with the present facilities for agricultural industry and intellectual culture, whose pursuit so profitably adorns and beautifies the state.”

While parts of this may be true, Wisconsin was not uninhabited wilderness. From another perspective, Rountree could be said to be able to look back on the days when he was an illegal settler on unceded lands the US government acknowledged as belonging to Native Americans; and he would have been able to recall the actions he took in an attempt to remove them from their ancestral homelands. From the perspective of the present moment, John Rountree’s legacy is darkened by the fact that the opportunities afforded to him were the direct result of the removal of Native Peoples and the expansion of white-settler government in the region —both of which Rountree actively participated in.

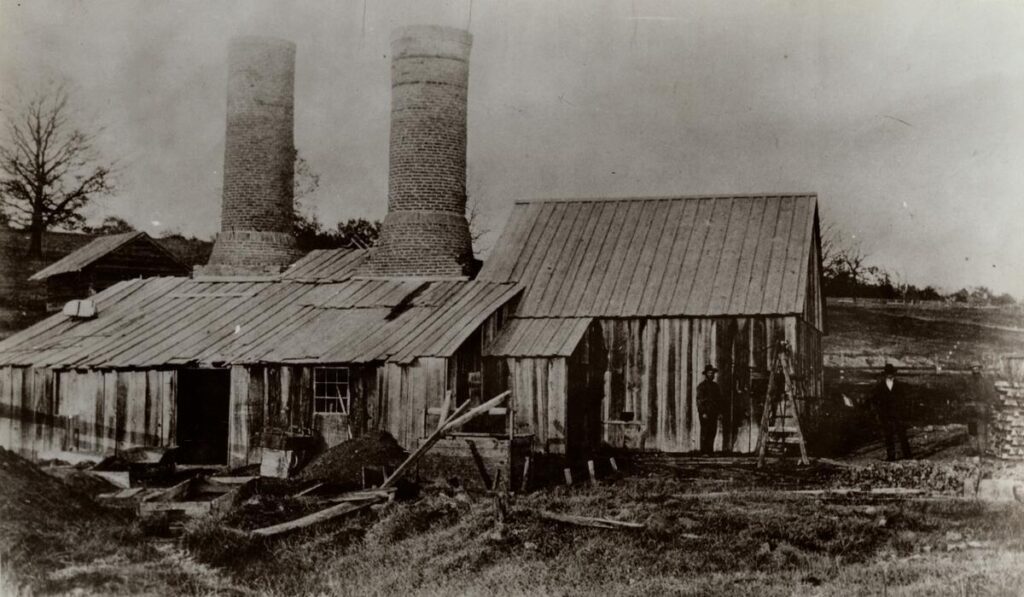

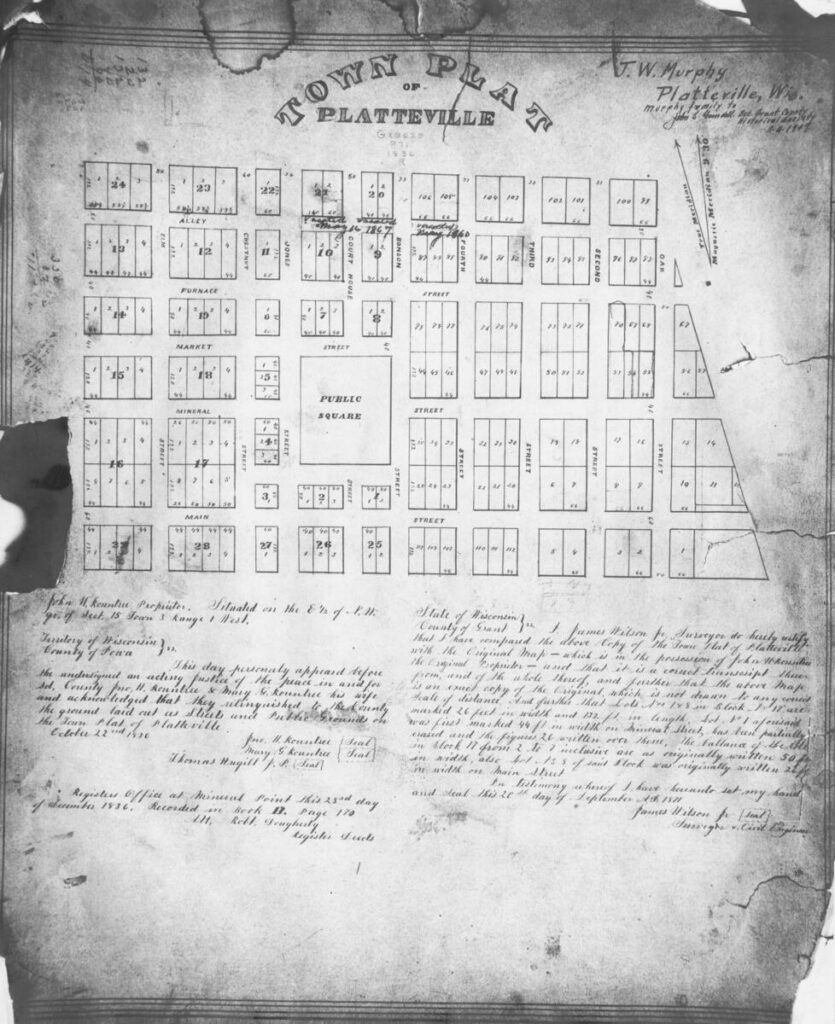

On 24th of May, 1827, John Rountree arrived in the state of Wisconsin with a small group of retainers, some oxen, and a driving team. He was 22 years old. When his party arrived, they constructed a sod cabin near the Platte River and began mining for lead. The region was just beginning to be settled by white settlers, and still was filled with a great many Native Americans who had treaties with the United States that acknowledged their right to the land. Hundreds of white miners had been arriving and illegally settling southwest Wisconsin’s lead country since a few years before he arrived, and Rountree immersed himself in the mining pioneer culture of the region, seeking to build his wealth. In addition to mining lead, Rountree’s ledger books show that he was quite the entrepreneur. He constructed a lead furnace that offered smelting services to other miners. He made extra money by offering other settlers loans and by buying and selling supplies.

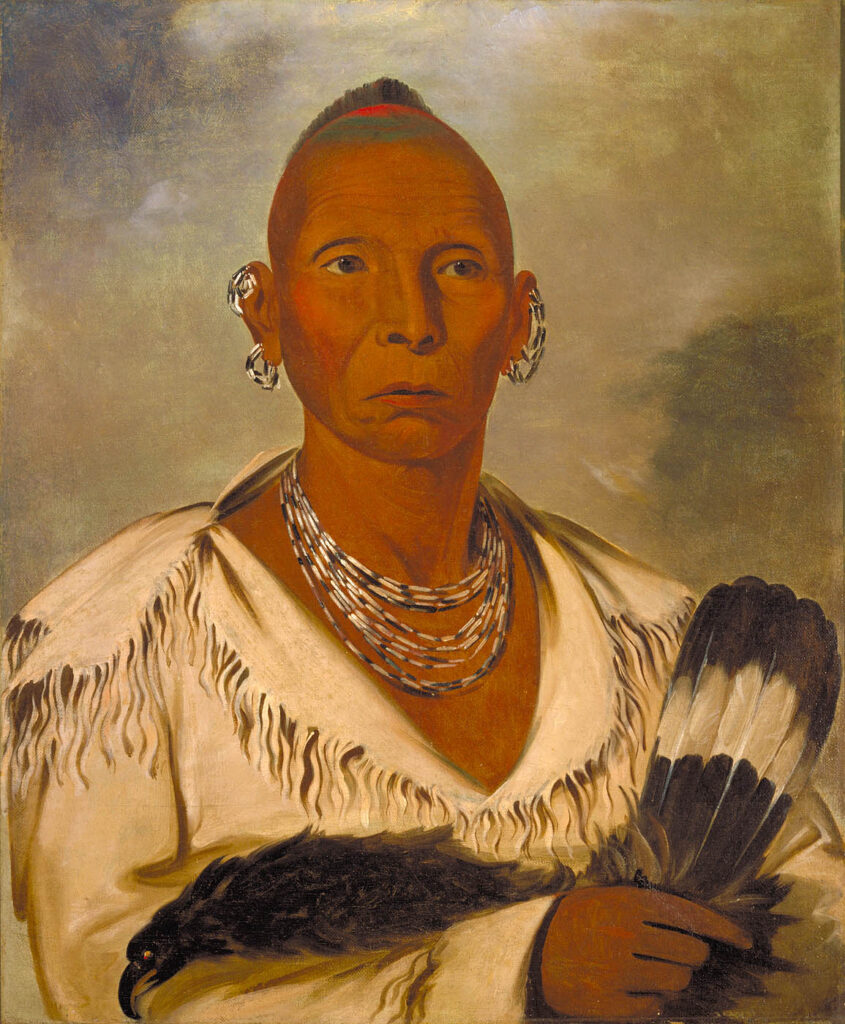

Rountree and his party were temporarily driven from the area he had settled in by hostile Native peoples. This would have been a traumatic experience for him, and it informs his participation in the Black Hawk War. This war is said to have begun with open hostilities in the state of Illinois, just to the south of Wisconsin’s lead mining region. Federal troops chased a party of Native peoples led by Sauk leader Black Hawk (Múk-a-tah-mish-o-káh-kaik) into what is today Wisconsin. By the time this war started in 1832, Rountree had amassed enough wealth and influence to raise a party of 100 cavalrymen to serve under him in the war. He joined the volunteer forces of the lead mining district, which had begun as a vigilante militia, but were soon were deputized into the U.S. army to aid in hunting down Black Hawk’s party. Historian Patrick J. Jung argues that, “The most significant consequence of the Black Hawk War was that it gave the federal government a great deal of leverage over regional tribes…After the Black Hawk War the pace of land cessation treaties picked up significantly, and within two decades virtually the entire region passed into the hands of the federal government.” After capturing Black Hawk, federal forces — seeing the quality of their homeland and hearing the exhortations of early settlers of the territory like Rountree —stayed to defend the area from future uprisings. Native peoples were coerced into treaties which ceded their rights to their ancestral lands.

John Rountree returned from the war with his interests now secured from threats from hostile native peoples. With the territory on its way to statehood, Rountree expanded his landholdings by purchasing property from the U.S. land office in 1834, legalizing his claim. His plan was to use this new plot of land, now cleared of Native Americans, to get even richer. Rountree platted and sold off small plots of land for new residents and businesses in the town.

After the founding of his town, Rountree would serve in a number of government offices, and he used his political power to promote Platteville’s growth. He served first as Platteville’s postmaster before being appointed chief justice for the district. Beginning in 1838, he served as a representative of Grant County on the Wisconsin Territorial Council, and then as a delegate to the Wisconsin State Constitutional Convention. In 1839 he was appointed as an aide to the governor of the territory with the rank of colonel, and was for years actively involved in the state militia. In this role he was directly involved in the removal of Native people from the territory and the protection of white settler interests. After Wisconsin achieved statehood, Rountree served in the state senate and state assembly numerous times, switching from the Whig, to the Democratic, to the Republican party in the course of his political career. During this time, Rountree built several new small businesses in the town of Platteville; he became a director of the Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Company, and he was instrumental in bringing the Chicago & Northwestern Railway to Platteville. Rountree died in his mansion in 1890 as a very rich and much respected man. He had lived a life that most 19th-century pioneers had aspired to.

Yet it’s important to remember that Rountree was a leading figure in Wisconsin’s removal of Native peoples, and much of his wealth and success was dependent upon interventions of the federal government — first in removing the Natives who threatened his interests from their homelands, then in legitimizing his land claims by selling him the property that became Platteville and its surrounds. Rountree’s work in government was never separated from his business interests, and he grew more wealthy as the presence of Native people in Wisconsin diminished. Rountree’s legacy is further darkened by the fact that he kept three enslaved persons in bondage in spite of the illegality of slavery in the region. According to research by Eugene Tesdahl, Rachel was purchased by John Rountree in 1827 to work as a servant to his new wife. In 1830, Rountree purchased a 19-year-old black woman by the name of Maria, and her 18-month-old son, Felix, in Galena, Illinois for the sum of $330. All three were made free by 1842, but Rachel remained with the Rountrees until her death in 1854 — after which she was buried in the Rountree family cemetery, her grave marked by a small stone engraved only with the initial “R”. While we shouldn’t simply cast Rountree as a villain, our duty as citizens today is to look at a historical figure like Rountree with a critical lens, so we can learn from the flaws of the culture and practices that built this country in order to help make it a better one in the future.

Written by John O’Brien, July 2025.

Sources

“John H. Rountree Dead.” The Daily Tribune (Wisconsin Rapids), 5 July 1890: 3.

Patrick J. Jung, The Blackhawk War of 1832. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2008.

Arthur Moody, “Life Sketch of J.H. Rountree,” Platteville Witness, November 1934.

Charles Tuttle, “Hon. John H. Rountree,” in An Illustrated History of the State of Wisconsin, Boston: B. B. Russell, 1875: 757.

Eugene R.H. Tesdahl, et al. “African Americans in the Lead Mining District,” The Mining & Rollo Jamison Museums of Platteville (online exhibit), 2023. https://mining.jamison.museum/african-americans-in-the-lead-mining-district/

Wisconsin Historical Society, “Rountree, John Hawkins 1805-1890,” Historical Essay. https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS12526