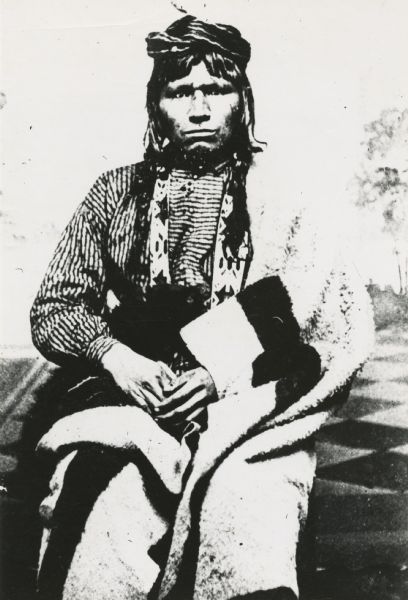

Ogimaa Weigiizhig (sometimes Ahgamahwegezhig, also known as Chief Big Sky and Old Jackson) was a leader of the Ojibwe, Lac du Flambeau Band. Late in age, in March 1914, he spoke to a reporter at Lac du Flambeau about his capture of the eaglet that would go on to become Old Abe. While the reliability of the reporting is dubious, this is the best-known account of Ogimaa Weigiizhig, (reportedly) in his own words:

It was long ago. I was the son of a chief. Thunder-of-Bees w[as] my father, and he was the chief of the Flambeau tribe of Chippewas. My mother I never knew; she died while I was a papoose.

It was shortly before the big battle, when the soldier marched away. Sugar making time had come, and the big snow had gone, and our band was happy at work and play. One day, while hunting, I noticed in the top of a tall pine tree, a great nest of mud and sticks. I knew it to be the home of an eagle. I watched it for hours. The old birds circled and swooped about the nest, time and again, so I knew there were young ones there.

I tried several times to climb to the aerie. The work was hard, and the parent birds fought stubbornly. Even I, most agile of the Flambeaus, could not reach the top of the giant tree. Still, I wanted the little ones. I had a steel axe, which I had traded from the white men, and this I took. Then I cut down the tree. It was hard work. For half a day I hewed and chopped; other young braves laughed at me; my father was not pleased; but I persisted and at last it fell with a crash like thunder.

Then came the fight. The parent birds swept down, trying to beat me off with their sharp talons, I fought them until they flew away. Then I gathered in my prize. There had been two young birds in the nest. One was killed by the fall. The other, still an eaglet, I took to my tepee, where it was fed by the squaw and papooses with bits of meats and scraps from the camp kettle.

Three or four weeks I kept the little eagle; but when the full moon came and the weather grew warm, Thunder-of-Bees led his men down the Flambeau river to trade with the white men. Maple sugar, furs and moccasins formed our stores. I took my eaglet with me. Down there I met a man. His name was Daniel McCann and he lived at Eagle Point. He offered me a bushel of corn for my bird. I took the offer, –why should I not? The eagle was not larger than a chicken, and a bushel of corn was a bushel of corn. He took it away. That is the last I ever saw of it.

But I have heard since, I have heard that McCann gave the bird to the soldiers and that it was in the big fight with them. But of this I do not know.

Joseph Barrett's Account, for the Northwest Sanitary Fair of 1865

The earliest published story of Old Abe was written by Joseph O. Barrett of Eau Claire, who claimed that he had collected the stories of “valid witnesses,” and he dedicated the book to sick and wounded soldiers. His version of the story begins:

One sunny day, about noon, O-ge-mah-we-ge-zhig, and his father-in-law and two sons, and his cousin, took each his canoe, with gun and dogs, for a grand hunt. Just as they swooped up the rapids, O-ge-mah-we-ge-zhig heard a melodious whistle above them, and looking up, saw a strong Eagle gaily swimming in the air, carrying in her talons a fish, evidently disturbed at the intrusion. Holding his canoe still, his quick eye followed her devious course until she alighted in that thicket of pines, on one of which, far up almost to the top, he dimly discerned her nest. One shot from his unerring gun would have brought that bird down bleeding at the heart; but knowing that at this season she was rearing her young, he suggested to his friends that her life be spared.

By right of discovery and contiguity to his wigwam, O-ge-mah-we-ge-zhig was acknowledged to be the lawful claimant of the nest. Many a time did he and his little family watch with prophetic hope those parent birds, as they came from the lakes, laden with their prey for the eaglets; and as often did they visit the tree, and look up through the tasseled branches to the broad nest, trying to catch a glimpse of their unfledged darlings.

When the sun had ascended to his northern tropic, O-ge-mah-we-ge-zhig thought it prudent to capture his eaglets. One week’s delay might be too much, for they were growing rapidly. So he and his men, taking their little dull axes, commenced the slow process of cutting down the nest-tree, for it was impossible to climb it.

At this time the old birds were away hunting for food. Round and round they hacked, severing but little more than a fibre at a time; but perseverance conquered, for there came a creaking, then a reeling, then a dying groan, then a crash. Giving the war-whoop, O-ge-mah-we-ge-zhig sprung to the tree-top, which broke in the concussion, just as the two eagles slid out from under the brush, running into the grass to hide. With a bound he caught the larger eagle, laughing outright, and one of his companions caught the other, which by accident received some injury not then discoverable. They were not quite as large as prairie chickens, being but a few weeks old, and were covered all over with a darkish down. When they had reached the camp — distant about three-quarters of a mile — the four squaws and flock of children came out to meet them with smiles, joyfully exclaiming, ” Mee-ke-zeen-ce! Mee-ke-zeen-ce! (Little Eagle.)

As the ” Eagles were so pretty,” they made a nest in a small tree, close by the wigwam of ” Chief Sky,” after the style of the old one, and there fostered them with vigilant fondness, feeding them with fish, venison, and other meat. The smaller one soon pined away and died, and sad indeed was the little colony.

On the day of moving to the Indian village, soon after, first, in the inventory of household goods, was the Eagle, on which was now lavished a double affection. For him a space with a grassy-bed was specially reserved in O-ge-mah-we-ge-zhig’s canoe. On landing at the village, old and young, like chattering blackbirds, crowded around the Eagle, each grunting delight in true native vigor. Bless him, what a pet to love! Ah-monse was particularly pleased with him, ” he was so smart and tame.” He was so domesticated as to need no confinement whatever, but would sit the live-long day, demurely watching the playing dogs and children, and patiently waiting for a wiggling fish from the lake.

O-ge-mah-we-ge-zhig wanted food for his hungry children; what should he do? After due deliberation, he determined to sell his Eagle to the white man at Chippewa Falls, or Eau Claire. Four Indians — neither of whom helped in capturing the Eagle — were going down to these towns to trade off their furs, and he proposed to join their company, adding to his own cargo his favorite bird.

Passing over the lakes and river, and stopping one night at ” Brunet’s,” — where for the first time our Eagle was caressed by white men — and awhile at the portage of “Jim’s Falls,” they drew their two canoes to the shore of the Chippewa, near the residence of Daniel McCann, who, by accident, met them there, and casually asked, ” where are you going? ” With an awkward spring, the bird slipped into the water for a bath, which amused the spectators vastly; and as the Indian drew him out, McCann inquired, ” What in the world is it? ” On being informed that it was an eagle, he bantered O-ge-mah-we-ge-zhig to sell him. Troubled at the thought of parting from his pet, he told the white man that he did not know what the Eagle was worth, and, looking longingly at him, added with a half-earnestness, that he wanted to take him back to his wigwam. At last, McCann offered a bushel of corn, which, on serious reflection, was accepted with the proviso annexed — Indian always — of something to eat. The price was duly paid — the Eagle was sold! The Indians then ambled off to the market, where they remained that night.

Compiled by Travis Olson, May 2025.

SOURCES

“Chief Sky, Now Blind and Helpless, Tells Story of ‘Old Abe,’ War Eagle,” Eau Claire Leader (Eau Claire, Wisc.), 27 March 1914, 6.

Joseph O. Barrett, History of “Old Abe,” the Live War Eagle of the Eighth Regiment Wisconsin Volunteers. Chicago: Dunlop, Sewell & Spalding, 1865.