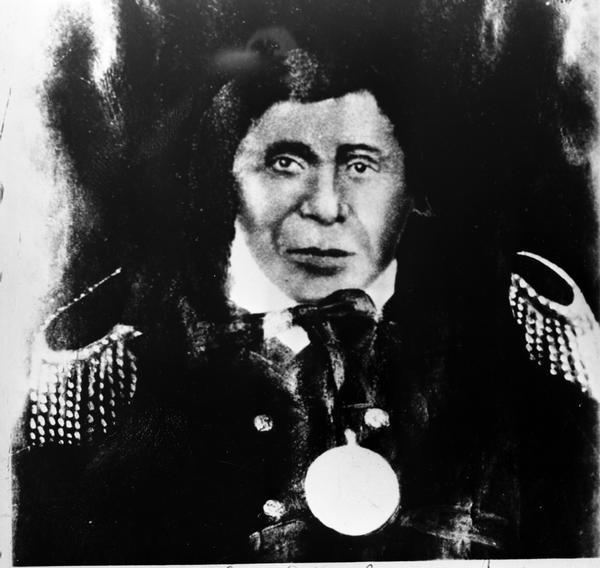

Ke-che-waish-ke (Great Renewer) (c.1759 – 1855), also known as Chief Buffalo (Peezhickee), and by the French Le Boeuf, led the Lake Superior Ojibwe people of Mooningwanekaaning (Madeline Island). Ke-che-waish-ke was instrumental to signing treaty agreements between the Wisconsin Ojibwe people and the United States, beginning with the treaty of 1825 and ending with the treaty of 1854. Known for his work to ensure a conservation of lands for Native Americans in Wisconsin, he resisted aggressive land acquisitions by the United States government. Unlike the physically aggressive means of conflict resolution practiced by neighboring Ojibwe tribe leaders, Ke-che-waish-ke was unique for his use of non-violent negotiations with other tribes and the United States government. Just as his people valued his impressive oratorical skills, other Ojibwe tribes from La Pointe began to recognize his skill and recruited him to serve as their spokesperson in negotiations with the United States.[1]

Ke-che-waish-ke first served as an authority representing a group of Native American Ojibwe tribes in the Lake Superior region for the treaties of 1837 and 1842. The Native peoples highly regarded Ke-che-waish-ke’s input and delayed the proceedings of the treaty of 1837 until he joined them near modern-day Minneapolis several days later.[2] While details about the Treaty of 1842 signing are scarce, Ke-che-waish-ke’s position as a figurehead for these tribes is evident in a letter he wrote several months later. In the letter, he described the treaty and his distaste with the strong-arming of the U.S. Government during the proceedings.[3] The treaties suggest that the United States Government intended to gain control of the La Pointe Band region in Northern and Western Wisconsin to access lumber and metal resources.[4]

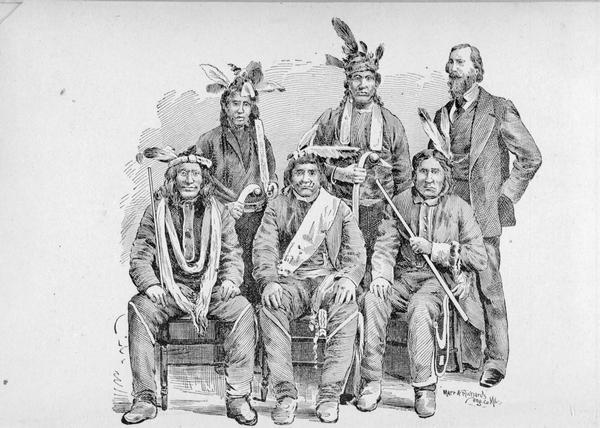

At 93 years of age, Ke-che-waish-ke traveled to Washington D.C. with a group of Wisconsin- and Minnesota-based tribal leaders to discuss ongoing injustices of land and resource control by the U.S. Government with President Millard Filmore.[5] In response, President Filmore rescinded the previous Indian removal order, going against a precedent of Indian relocation from their homelands seen across the United States.

Ke-che-waish-ke’s role as a leader for the Ojibwe people culminated with the La Pointe Treaty of 1854, which solidified his memory in history. In these negotiations, the Native American leaders ceded most of their land on the Wisconsin shores of Lake Superior to the U.S. Government, in return for a guarantee of annual payments, as well as usufructuary rights.[7] These protections allowed for Native peoples to continue using the ceded lands for hunting, fishing, and gathering purposes, regardless of any laws that would restrict United States citizens from doing so.

Not long after, Kechewaishke died in 1855 and is buried at La Pointe Indian Cemetery on Madeline Island.

Written by Trase Tracanna, February 2021.

SOURCES

[1]William W. Warren, in History of the Ojibways, Based upon Traditions and Oral Statements (St. Paul, MN, 1885), p. 48.

[2] Ronald N Satz, “Appendix 1,” in Transactions of the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters, ed. Carl N Haywood, 1st ed., vol. 79 (Madison, WI: Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letter, 1991), pp. 131-133.

[3] Ronald N. Satz, in Chippewa Treaty Rights: the Reserved Rights of Wisconsin’s Chippewa Indians in Historical Perspective (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1997), p. 40.

[4] “Ojibwe Treaty Rights,” Milwaukee Public Museum, accessed February 2, 2021, https://www.mpm.edu/content/wirp/ICW-110.

[5]“Miskwaabekong History,” Welcome to Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, accessed February 2, 2021, https://www.redcliff-nsn.gov/community/heritage_and_culture/miskwaabekong_history.php.

[6] “Be Sheekee, or Buffalo,” U.S. Senate: Be sheekee, or Buffalo, January 12, 2017, https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/art/artifact/Sculpture_21_00002.htm#bio.

[7] Stone, Andrew. “Treaty of La Pointe, 1854.” MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/event/treaty-la-pointe-1854 (accessed February 16, 2021).