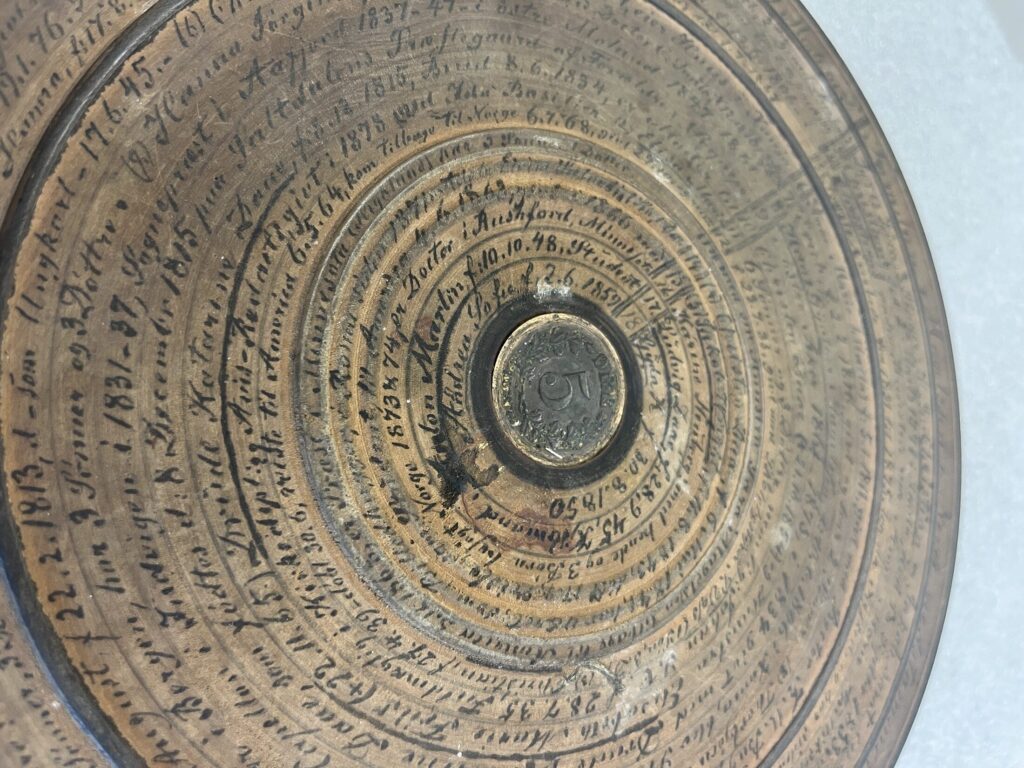

In 1879, Hans Gunther Magelssen approached a jeweler in Oslo, Norway to have him make a gift for his granddaughter-in-law, Sara Magelssen. Into the backside of a 9.5” diameter wooden plaque the jeweler inset a 5 Øre coin. While beautiful, what sets this object apart is what is inscribed on the back of the plaque around the coin – the Magelssen family genealogy.

In eighteen concentric circles, the family’s history is handwritten in Norwegian, noting births, deaths, and marriages as it traces their journey from Germany to Norway. For Sara and her husband Kristian, their journey, like thousands of other Norwegians in the mid-19th century, brought them to the United States. Their story, including their immigration to Wisconsin in the 1860s, is written on the 12th and 13th lines of the object.

Alice Alderman, a librarian at the Wisconsin Historical Society, translated Magelssen’s writing. Kristian was born “27 April 1839, baptized 30 June. Went to America 6 May 1864, came back to Norway 6 July 1868, married 29 October 1868 and went with his wife Sara Magelssen back to America 5 December 1868.”

Upon returning to America, Kristian became a pastor in Highland, Minnesota, and their family had 2 sons and 1 daughter.

This disk and the history of Norwegian immigration to Wisconsin and resettlement within the region illustrate some important features of Wisconsin’s Norwegian community. Norwegian immigrants established communities in Wisconsin’s southeast and south-central regions beginning in the 1830s and 1840s.[1] By 1850, Wisconsin was home to 9,467 Norwegians, and by 1870, as they settled further west, the number reached 59,619 individuals.[2] Approximately 41% of all Norwegian immigrants in the United States were women.[3]

Written by Jared Lee Schmidt, July 2019.

FOOTNOTES

[1] Marcia C. Carmichael, Putting Down Roots: Gardening Insights from Wisconsin’s Early Settlers (Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2011), 87; James P. Leary, “Norwegian Communities,” in Encyclopedia of American Folklife Vol. 3, edited by Simon J. Bronner, (Armonk: M.E. Sharpe, 2006), 892-896; Odd S. Lovoll, introduction to Wisconsin My Home: As told to her Daughter Erna Oleson Xan, 2nd Ed. by Thurine Olseson, (Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2012), xii-xiii.

[2] Lovoll. xiii.

[3] Odd S. Lovoll, “Norwegian Immigration and Women,” in Norwegian American Women: Migration, Communities, and Identities, edited by Betty A. Bergland and Lori Ann Lahlum (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2011), 51.

This object has been featured on WPR's Wisconsin Life!

Produced for Wisconsin Life by Maureen McCollum and Heewone Lim

Many people preserve their genealogy through family trees, mapping the branches and roots out on paper. Heewone Lim brings us the story of a unique genealogical work of art: a Norwegian genealogical plaque.

Listen below to the segment from Wisconsin Public Radio’s Wisconsin Life.

Maureen McCollum:

Many people preserve their genealogy through family trees, mapping the branches and roots out on paper. Heewone Lim brings us the story of a unique geological work of art, a Norwegian plaque. It’s part of the Wisconsin 101 collection, which tells the history of the state through objects.

Heewone Lim:

In 1879, Hans Gunther Magelssen of Norway commissioned a jeweler in Oslo to create a gift for his granddaughter-in-law, Sarah Magelssen. The gift was a round wooden plaque inset with a five Øre coin, the equivalent of a nickel. Surrounding the coin are 18 circles of names and important dates chronicling the Magelssen family genealogy. The dates note births, marriages and when people emigrated to the United States. Dana Kelly is the executive director at the Norwegian American Genealogical Center and Naeseth Library. She says this plate is a one-of-a-kind genealogical artifact.

Dana Kelly:

The things that they brought with them were pretty utilitarian, but to have just an artistic object like this was pretty unusual.

Heewone Lim:

Kelly says the center sees other genealogical objects such as trunks with names painted inside the lid, or family Bibles, where a family has several generations of baptisms and marriages recorded.

Dana Kelly:

But obviously a Bible is not created just for genealogy. It’s meant to be a book. So this is unique in that respect, that it was created specifically for genealogy to tell the family’s history.

Heewone Lim:

Certain names on the plate are underlined over and over, which was a practice used in church records back in Norway, the Magelssens had ministers in the family tree, so they likely carried on this practice for generations.

Dana Kelly:

You know, I baptized so-and-so’s daughter, you know, Kari, he would underline Kari’s name because that was the important part. That was the child being baptized. It does kind of look like they’re doing that here, underlining the person’s name to accentuate who’s the important person on this line. So they’re keeping with that custom.

Heewone Lim:

The plate begins with a different Hans Gunther Magelssen, who was born in Hamburg, Germany in 1734 and emigrated to Norway in 1756. Magelssen’s German roots explain why the family has the same last name throughout the plate. Kelly says the practice of using a permanent family name was uncommon in Norway at the time.

Dana Kelly:

Their social custom was not to give children the same last name as their father. If their father’s name was Lars, the children would be Larsdatter or Larsson. So seeing that they refer to themselves as the family Magelssen would indicate to me that they have a cultural outlook that isn’t typically Norwegian. Perhaps they had had more experience with other cultures in Europe that have that permanent family last name.

Heewone Lim:

However, the family still kept some Scandinavian naming traditions. The plate features a few different names multiple times, Hans Gunther Magelssen, Sarah Magelssen and Kristian Magellsen.

Dana Kelly:

Names got used over and over and over again in Norwegian families that it was very common to name a child after their grandparent, and it wasn’t unusual to have more than one child in a family that had the same name.

Heewone Lim:

The value of this plaque both a carefully crafted artisanal object and a sentimental record keeper speaks of the dedication the Magelssens had to keeping Norwegian culture and their family history alive in the Upper Midwest, sending a family heirloom to America, a far away country with no practical purpose, reflects the journey of the Magelssen family.

Dana Kelly:

Something like this would have been something that they could display freely without having to worry about discrimination and what it might mean to cling to the old country, so to speak.

Heewone Lim:

By 1870, almost 60,000 Norwegians had settled in Wisconsin, and that included members of the magelson family the United States became known as westerheim, or the Western home

Maureen McCollum:

Heewone Lim brought us that story on the Norwegian geological plaque, which is part of the Wisconsin Historical Society’s collection. It’s also a part of the Wisconsin 101 Project, which tells the history of the state through objects. Wisconsin life is a co-production of Wisconsin Public Radio and PBS Wisconsin in partnership with Wisconsin Humanities. Additional support comes from Lowell and Mary Peterson of Appleton. I’m Maureen McCollum.

Wisconsin Historical Society

This object is part of the Wisconsin Historical Society collection in Madison, Wisconsin.